To Not Be Silent: A deep look into Micah Bournes’ new release “A Time Like This”

by James Andrew Carroll | Published June 7, 2018 in Arts & Culture

15 minute readTo be silent in an age of corruption is to be violent against myself

Which is somethin’ I will not do

– Micah Bournes, on the track, “Too Much?”

Unblinking, Micah Bournes sits forward at his bedroom desk, soaking in an eight-minute spoken word piece exploring the journey of a poet. The tale flows from broke to broke, in pockets and in hearts; from discovery to forgetting to revelation, and back. Bournes is basking for a moment somewhere—everywhere—on that journey.

A Time Like This is Bournes’ sixth release, his fourth full-length, and his first whole album dedicated to hip hop. Aside from the turn in genre focus—Bournes’ previous work included a lot of blues—this latest project from the Long Beach poet and musician also displays a new temper. The album opens angry, like an introduction that has kept itself unknown to us for too long—or one we keep refusing to hear.

Bournes paints both metaphors—the personal and the political; our power to speak and our power to listen—throughout the hour-long, 16-track exploration of America that touches on many subjects, including war, race, religion, and love. A Time Like This is an honest, balanced brew of anger and celebration, hope and frustration, coming from a perspective deeply self-identified as Black and Christian.

When I sat down with Bournes to discuss his music and its meaning, he told me his other releases came together in a patchwork way: “Living, writing, got a bunch of stuff, do an album.” But the election of Donald Trump mandated for Bournes a heightened urgency: “I have something to say right now.” The resulting songs were written between Trump’s January inauguration and the Fall of 2017, “directly responding to what was going on in the nation.”

Bournes struggled in that time period with the importance of immediacy—of getting the album out as soon as possible—and the depressing knowledge that its messages would likely remain relevant for much longer. Contradictions like this are contained throughout the work, lending it a realism and humanity, at times mirroring the nation’s struggles to those of Bournes.

Maybe there’s a reason I’m young Black and pissed

Maybe that’s exactly what we need in a time like this

– “A Time Like This”

For that reason, the “maybe” in these two lines from the album’s first track should not be taken to belie the artist’s conviction, but should be read more as the marker of a transitional experience from recognition to action. Both the opening entry and the following one, “Too Much?”, confirm in different ways that important bridge. The closing sequence of the first repeats “Made for a time like this,” echoing like an inner-voice of conscience, and inciting an immediate desire to join a struggle—or to recognize we are already part of one; but by ending with, “Maybe there’s a reason I was made for a time like this” (emphasis added), Bournes admits the task of our time is not so easy to accept.

Realizing the struggle that still exists for black people particularly begs the question of the second song, “Too Much?” Bournes addresses the natural next step: once you know something is wrong, you are forced to ask is that something wrong you?

No we ain’t never marched for diamonds

And never would demand your love

Just the air to breathe

The space to be

Equality, is that too much to want?

Smooth bass licks color the chorus, which reads, sounds, and feels like a prayer. Prayer is as much a hope as it is a question—it is part desire, part doubt. That contradiction is captured so well here, especially in the aggressive journey Bournes takes us on from self-defense to self-affirmation. The tune drops, leaving only the bass drum, and then loses that too, allowing Bournes the silence to answer the song’s question:

I am not too much.

I am not too much.

I am not too much.

My people be feisty

Don’t tell us to ask nicely

Only demandin’ what belongs to us rightly

Musically, “Too Much?” stretches from within itself to the other end of the album’s sound, justifying its early position on the release, and making it a kind of encapsulating summary of what we are in for: blues progressions, gospel harmonies, spiritual pleas, angry beats, and steady conviction.

It is that last quality that has caused Bournes some unique problems.

Though A Time Like This holds plenty of space for celebration, it also contains heavy criticisms from a place of genuine personal commitment, and that cost Bournes a lot of support during his fundraising campaign for the project.

“When I was promoting the Kickstarter, I was very honest about my perspectives, and that’s when I started to see the decline in invitations.”

Bournes says he lost fans, financial backing, and access to venues:

This is the struggle of artists generally, and marginalized voices doubly: keep quiet—or else. Bournes manages to maintain a calm perspective, joking, “The further left you go, the less money there is.”

A sweet bit of humor for us all to keep in our pockets—and dig for later when the money isn’t there. But while Bournes’ financial independence has suffered as a result of his politics, he knows the only alternative to using your voice—your real, authentic voice—is losing it.

Done lost my way if I rise to the top

of an exploitive system unjust and corrupt

– “Too Much?”

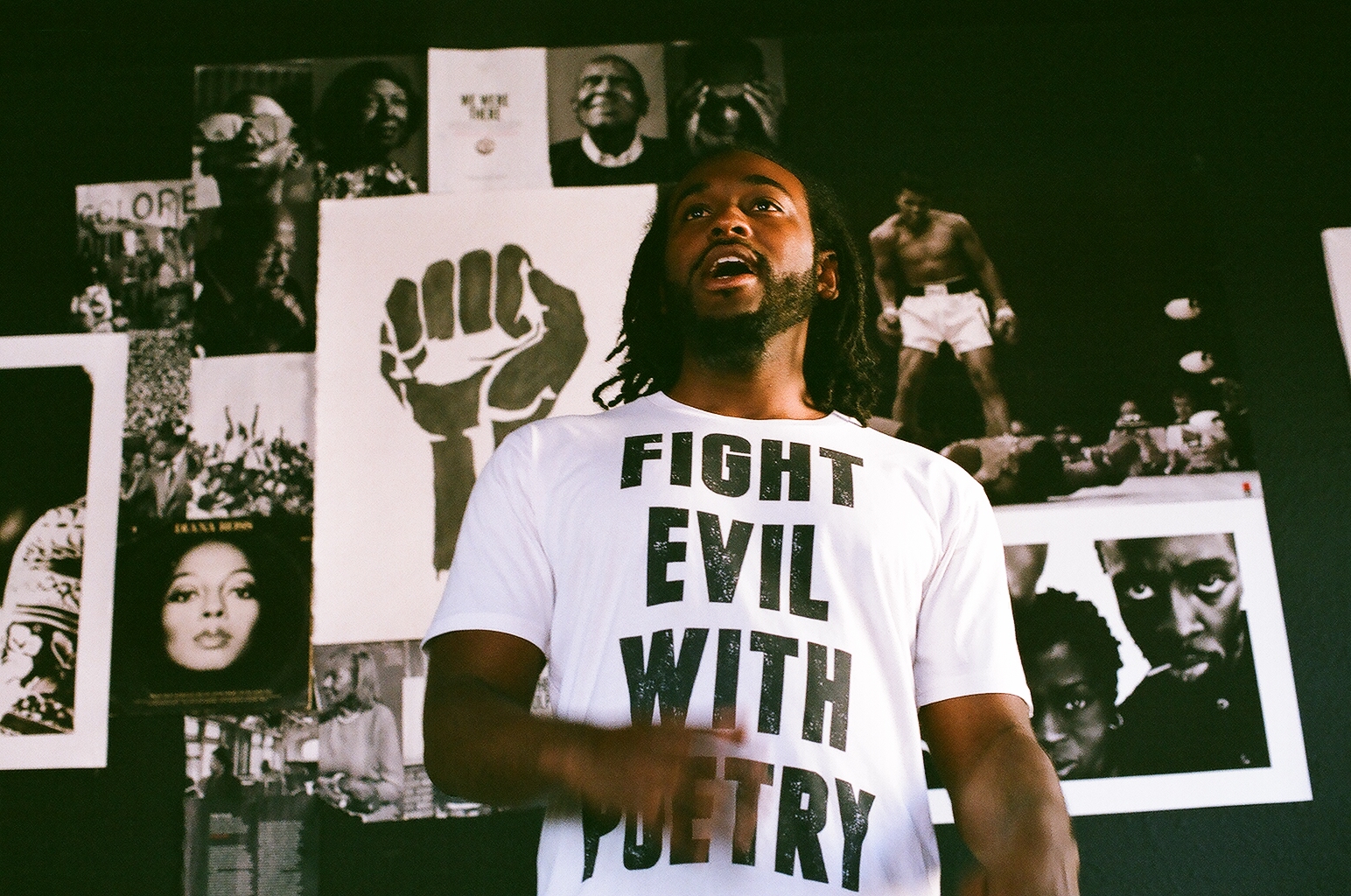

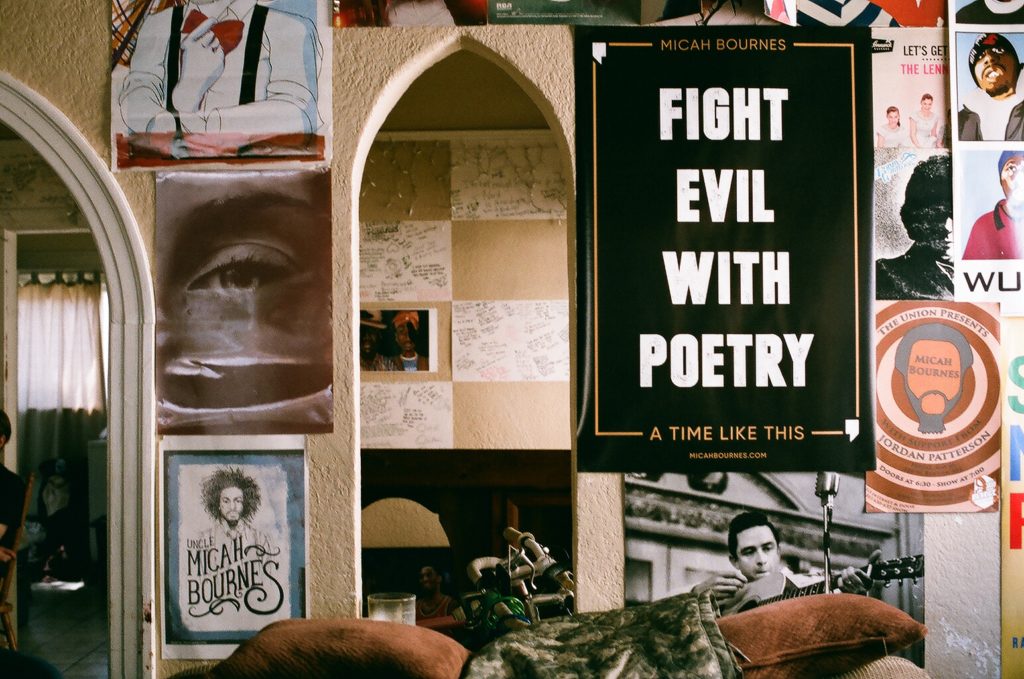

The track that caused the most backlash, according to the artist, is “Just War Theory.” For the first time on the album, Bournes travels into a spoken word monologue, resounded over an anxious, stalking, war-drum march. The departure to poetry in the midst, or at the height, of controversy serves as an example on multiple levels. Bournes’ mantra that we should “Fight evil with poetry” represents to him the ethic of using our talent—whatever it might be—for good, and so Bournes allows himself his own advice by using “Just War Theory” as an open mic stance against myriad hypocrisies of war. In the context of the full release, this is the equivalent of Bournes stepping away from the microphone to address the audience directly with his lungs—a tactic that focuses the direction of his words and our ears…

No disrespect to vets with post-traumatic stress

or soldiers who lost their life

But no one is a hero just ‘cause they fight

I am not grateful for your service

I don’t know what you did on tour

Even aside from possible war crimes

I’m not sure if I believe in this war

But this was not the only piece with targets close to home—“Fan Mail” also critiqued two groups crucial to Bournes’ artistic and personal development: fans of his early work, and Christians. When I asked Bournes if any group was particularly unsupportive of this next step in his poetic journey, he cautioned, “For the most part… conservative white folks.”

Tomisin Oluwole

Dine with Me, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

“Fan Mail” begins with a sampled television broadcast interruption, signalling that Bournes is about to break from his previous programming. The opening verse then offers warning—“By the end of this verse / You gon’ need antiseptic”—and ascends energetically like a flush. Once the frustration is drained, an ironically laid-back beat and droning melody line enter, mirroring the mocking lyrics, full of sarcasm, shoulder-shrugs, and a readiness to let go. “Fan Mail” defends in a more direct manner what the rest of the album embodies: a turn towards politics.

Laugh Micah laugh

Laugh Micah laugh

…we liked you better when you wasn’t so mad

The second community closest to Bournes is interrogated in preceding lines:

…let me ask you somethin’ Christian

If you think a Muslim is your enemy

and your Savior say to love your enemies

then you ain’t got no excuse and I really am confused

why you wanna ban Islamic Refugees

Sentiments like this are sure to please non-believers (among which I count myself) and other non-Christians, but it is important to note that the lines are not meant for us. We should refrain from using them as our own, easy weapons to jeer Christian hypocrisy; rather we should cheer the rare self-sacrifice of the artist. The ability to challenge your own roots—your own religion, your own politics, your own beliefs—is less common than it should be. While being on the inside allows Bournes the access and the knowledge to criticize in an intimate way—which he does here and elsewhere poignantly—it more importantly provides him the closeness to lead.

Knowing when to turn the mirror around and challenge those closest to you, and when to rally your peers in self-defense against external threats, is as much a distinction of a mature artist as is having fans to lose and being unafraid to lose them. Bournes may have climbed that mountain with this particular piece, and the resulting perspective spreads across the whole release, allowing him to aptly turn the mirror wherever he pleases, alternately using it to demand change or promote love.

My fan mail is turnin’ to hate mail

Oh well ‘cause the truth I’m gon’ tell

– “Fan Mail”

If “Fan Mail” and “Just War Theory” demand change, then love’s healing is found in tracks like “Kissed” and “The City of Long Beach.” I have been very happy to hear the latter—an old-school, cruise-through-town-with-your-windows-down, hip hop anthem—blasted between poetry breaks at The Definitive Soapbox open mic in North Long Beach. I not-so-secretly hope the song gets similar play as our city’s unofficial anthem in bars and cafes from Ocean to the 91.

The tune is followed by “Kissed,” an upbeat celebration of the beauty of black women. “Black has always been uglier,” Bournes tells me, noting the pressures he and others have felt to “breed the blackness out of [our] family heritage.” “Kissed” is appropriately easy to move to, matching its uplifting intent, and introduces to the project a pleasant acoustic guitar vamp and driving, Latin-influenced hand-drumming—perhaps reflecting, as Bournes notes towards the end of the song, “all the Latin folks with afros that don’t know they also Black.”

Bournes continues to heal us with two back-to-back tracks that are as unequivocal in style as they are undeniable mirrors on love in America: “Boo Thang” and “A Hill Worth Dying On.”

The first is dangerously catchy, bearing a feel-good message and feel-great melodies. Every listening thus far has successfully spiked my senses, forcing me to smile, shiver, and crackle in that cheek-to-cheek-with-my-most-loved-one kind of way. Piano chords splash gently in the background every four counts and resonate like naturally rhythmic ripples. The whole scene is appropriately clear, clean, and easy, allowing Bournes to confidently state:

This is pure matrimony

Even our nasty is holy

So ain’t no shame in the mornin’

You want two waffles or three?

That final, light-hearted question also serves as an argument against the manic desperation we often associate with romantic partnerships. Like the album’s and the artist’s wider intent to simply be allowed to exist—and to recognize that this existence is its own justification—“Boo Thang” teaches us to be okay with our self and others, breaking the album near the middle with an easy-listening reminder of what we are here for.

The topic slides into the next track, which succinctly counters the shamelessness of love with the shame of it.

“A Hill Worth Dying On” is built around a dialogue between Bournes and a white woman in a hypothetical romantic partnership. Their dueling series of observations reveals just how white one is, and how Black is the other. Bournes does well to amplify this starkness between himself as a Black man and this partner as a white woman, “Because it’s tradition to say I don’t, but I do see color / And I’m trying to see it better.”

The tune comes complete with playful piano ditties echoing hardwood church-floor acoustics, a wonderfully campy opening sequence, and a refreshing self-awareness that takes what begins like a parody skit of 1950’s America into an honest reflection on the problematic nature of interracial dating 70 years later. In our conversation, Bournes told me a true story, alluded to on the song, of once struggling to hold a white girlfriend’s hand “in a room full of Blackness.”

The piece culminates with the duo acknowledging that “it’s love that makes me want to understand our differences, not erase them.”

When I first considered writing a review of this album, I met with Bournes at his Westside Long Beach home to learn more about his message, and about our differences. It was 10 in the morning on January 15th, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, when I sat in his bedroom, filled with homages to Black beauty and power, and listened. Though it did not strike me at the time, I recall now in writing this review that for the full two hours of our discussion, Bournes never sat down—he stood and paced in front of me and spoke, or maybe preached.

That last word may feel, to many of us, a bit old or outdated—perhaps even inappropriate, to the extent we associate religion, and Christianity, with the American Right. But, Bournes informs me, “In the Black Church, that [association] has never been the case.” As he reminded me during our talk, while many today call King’s famous orations “speeches,” the more proper term remains “sermons.”

It is indeed easy in our modern image of King to forget that he was a preacher, that he gave sermons, and that he saw a prophecy. At the end of my conversation with Bournes, as we were discussing appropriately the final piece, “Humming Fools,” he carefully taught me something that I will not forget: in the prophetic state of mind, though our visions might appear insane to all those around us, we are in fact “closer to reality.” How? Because the prophecy of today may become tomorrow’s reality, and that means it is not our prophecy, but our reality, that is furthest from the truth.

Yes, we were there

way back then

being mocked and dismissed by most

but we never were ashamed

We never stayed quiet

We were there

telling stories of a day when impossible

things would be daily routines

– “Humming Fools”

Micah Bournes insists in the opening track, “I am not a prophet why you givin’ me these visions,” but A Time Like This feels deeply like a revelation.

You can listen to A Time Like This at Micah Bournes’ official bandcamp.

All photographs in this series by Madison D’Ornellas.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org