'It is Misleading': Consultants Say City Promised Millions in Tax Money Under Guise of Creating Affordable Housing at the Oceanaire

Story and Graphic by Kevin Flores

Published August 23, 2021

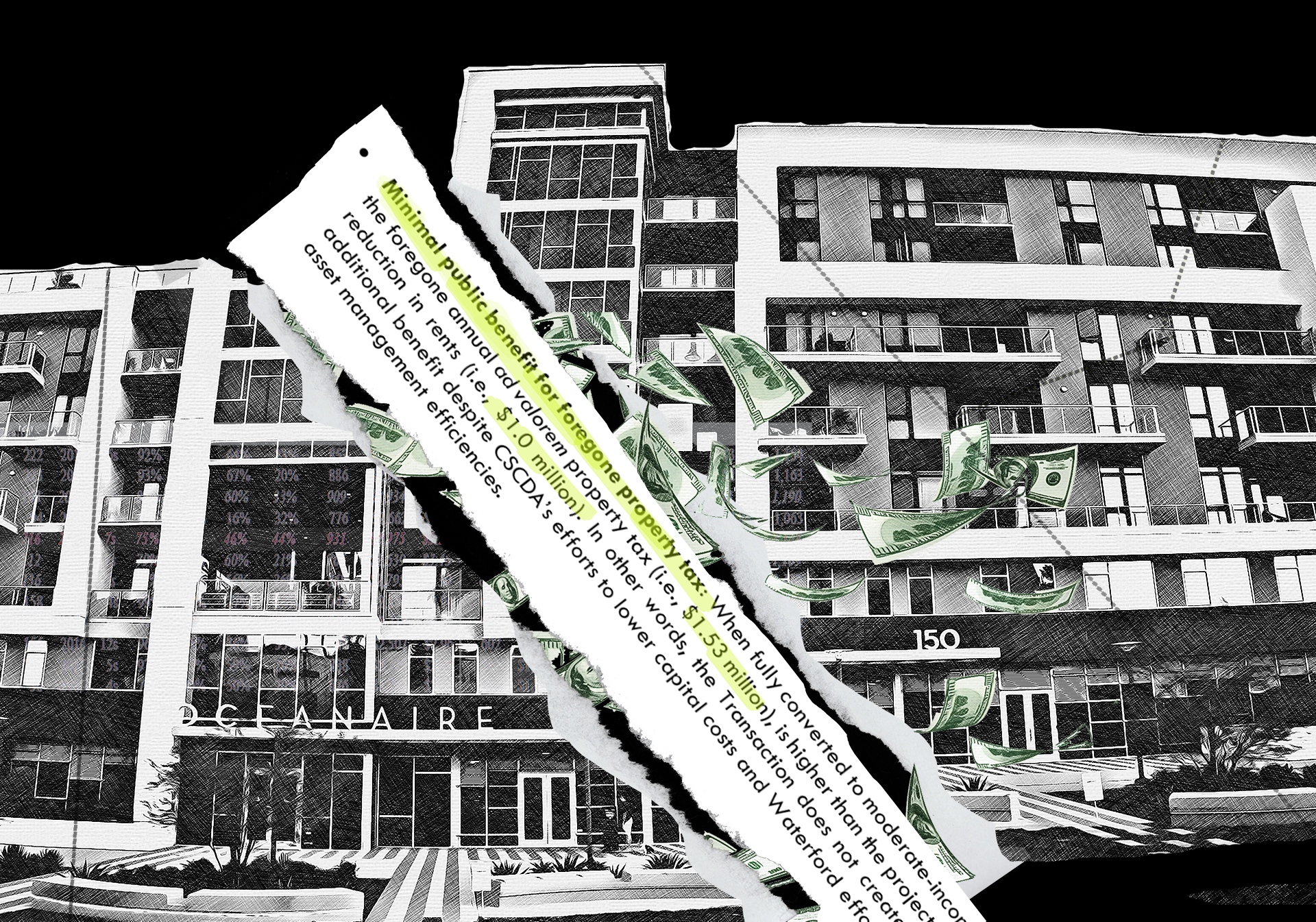

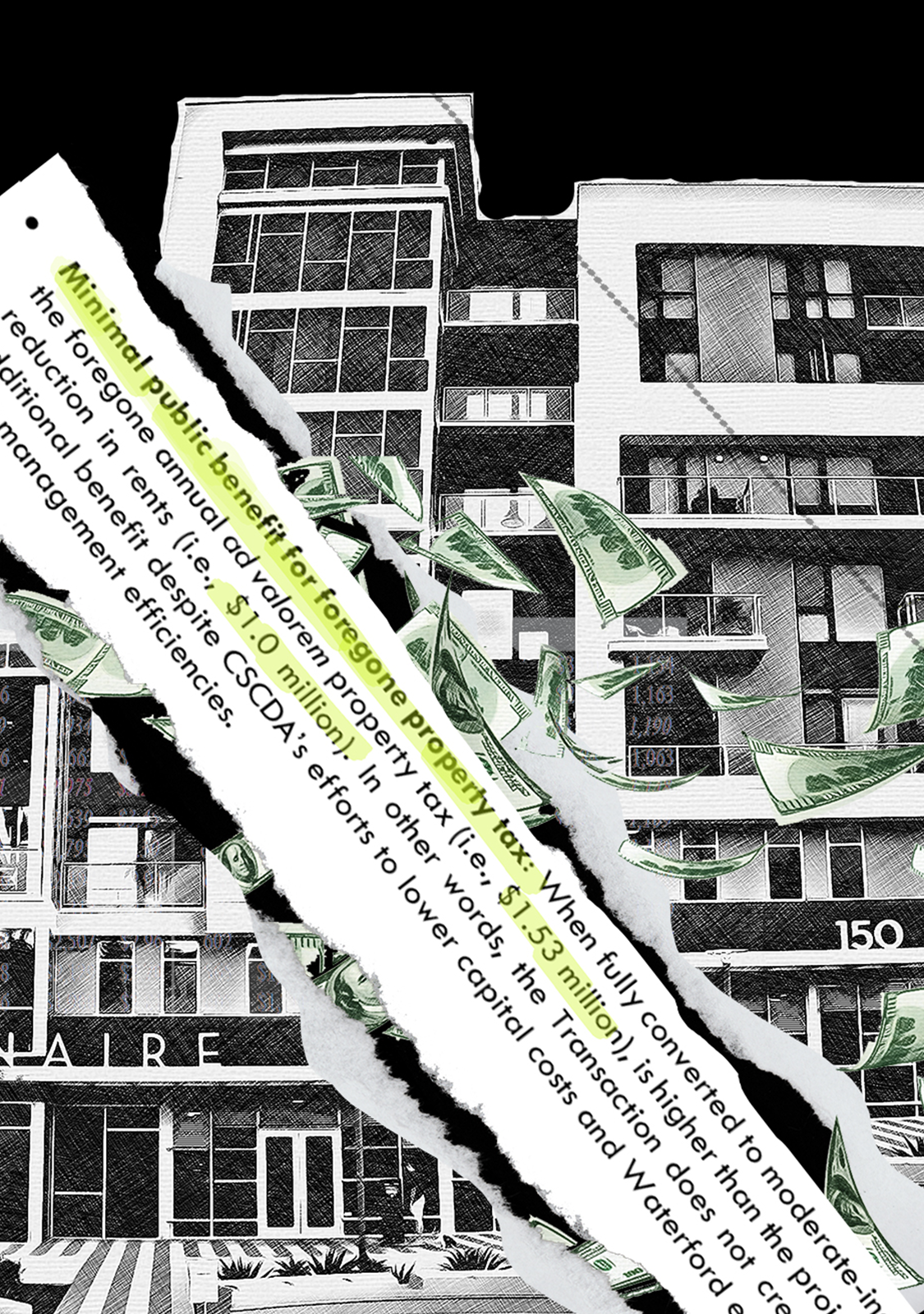

A complex financial agreement approved by the City Council in February to convert the Oceanaire building downtown into income-restricted housing will provide the project with up to $43 million in property tax subsidies over three decades in exchange for little public benefit, according to a newly uncovered analysis from a consulting firm hired by the city.

Enthusiastically touted by members of the council as an innovative way to increase housing for moderate-income households, the consulting firm instead warned that the multi-pronged deal leaves Long Beach with “modest affordability benefits, a financial structure that is misaligned with City interests, and a return on public investment that does not provide clear justification for participation.”

The document also notes that Waterford Property Company, a well-connected real estate investment firm notorious for displacing low-income tenants in Long Beach, stands to see the biggest guaranteed payday from the deal. The company will rake in an estimated $11.5 million over the next 15 years in fees while taking on little to no risk, the report says.

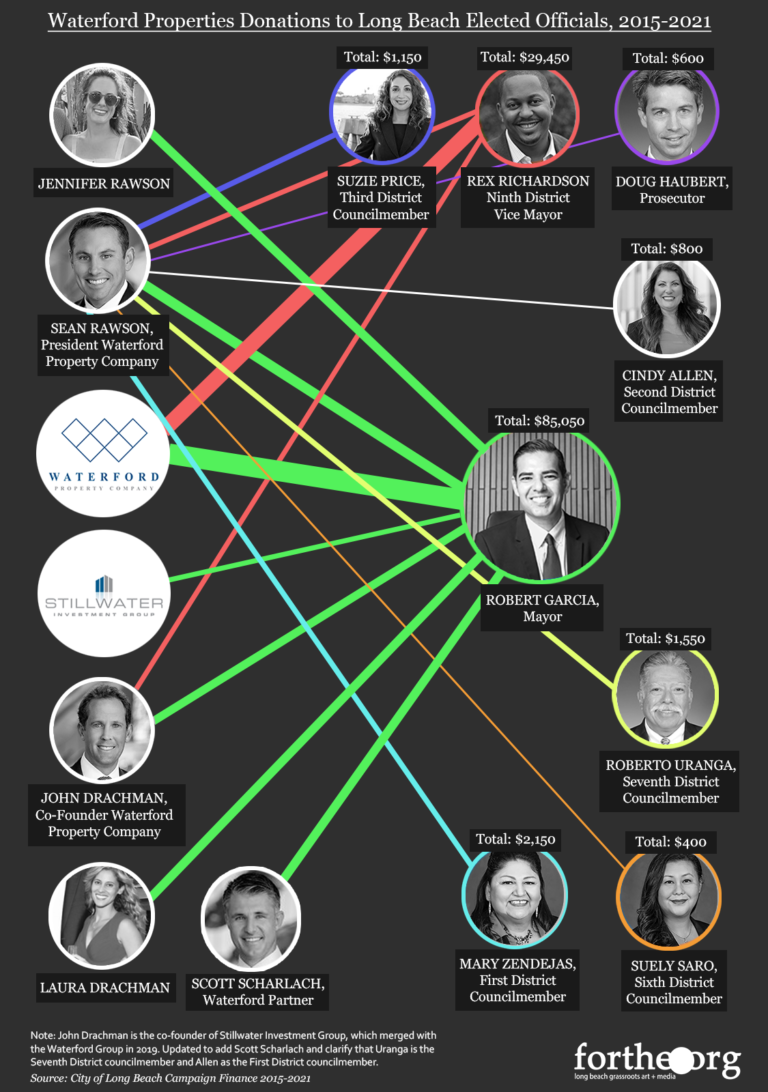

According to campaign finance forms, Waterford has given over $126,000 to current Long Beach politicians in recent years. The largest of those political donations were to the mayor’s Robert Garcia for Lt. Governor 2026 committee, which received $38,800 in contributions from three Waterford executives and the wives of two of those executives in the months following the council’s approval of the financial arrangement.

The independent analysis of the deal—which all councilmembers received but was not made public by the city—was prepared by HR&A Advisors, a nationally recognized real estate consulting firm that has advised Long Beach on various major undertakings, such as the development of the new Civic Center complex. FORTHE Media obtained the analysis only after it appeared as an appendix to a report on a similar project from the City of San Jose in April.

In a nutshell, here’s how the deal works: the California Statewide Communities Development Authority (CSCDA), a state agency, issued tax-exempt bonds on behalf of Long Beach to buy the Oceanaire in March for $121 million. Because the CSCDA is a public agency, the building became exempt from property taxes once it was purchased. This in turn cut operating costs enough to pass on some of the savings as rent discounts to moderate-income households. To qualify for a unit, a family of four would need to make between $90,000 to $135,00 a year.

This left the CSCDA as the official owner of the Oceanaire, a 216-unit luxury apartment complex on Ocean Boulevard built in 2019 that offers ocean views, a yoga lawn, and a Bali-inspired water courtyard with a floating lounge. Meanwhile, Waterford became the project administrator, in charge of overseeing Greystar, the building’s new property management company. The city’s role as “host” is governed by a public benefit agreement, which authorizes the bond sale and precludes Long Beach from incurring any financial liability for the bonds or the property. After 15 years, the city can take ownership of the building and sell it.

The move is part of the CSCDA’s Workforce Housing Program, through which the joint powers authority has issued over $2 billion in bonds to purchase luxury apartment buildings in various cities across the state, including Carson, Anaheim, and Pasadena, with plans to convert the properties into what is supposed to become moderate-income housing.

And despite the warnings in the HR&A study that such a deal would cost local taxpayers more money than the housing affordability it would create, it sailed through the City Council, making Long Beach the largest city to participate in the program.

This eight-part investigation delves into the mechanics of the Oceanaire deal, explores the wide-range of Waterford’s local political entanglements, and probes the fundamental question of whether Long Beach taxpayers are getting a fair shake.

This investigation took over 200 hours. It involved sifting through hundreds of pages of documents, interviewing experts, writing, editing, and photographing, along with graphic and web design. FORTHE is a fully independent volunteer organization that needs reader donations to continue doing work like this. You can make a one-time contribution or sign up to become a monthly donor at the button below. Even a small amount helps.

A MODEST PROPOSAL?

Part I

One of the main points over which supporters and critics of the program have butt heads is whether the rent savings created at the Oceanaire are an adequate return on taxpayers’ investment of millions of dollars in property taxes.

HR&A’s analysis found that rents at the building will only be “meaningfully decreased” for 87 of the Oceanaire’s 216 units, with 103 units ultimately exceeding market-rate rents.

“The affordability gains are relatively limited compared to the foregone property taxes that could be used for other public purposes,” the analysis states.

According to HR&A, the 87 units priced for households earning 80% of the area median income (AMI)—about $90,000 a year for a family of four—will on average see a 28% rent drop. That means the price of a one-bedroom apartment for this income bracket will fall from $2,564 to $2,102 a month.

However, the consultants noted that the rest of the units will see only a “very modest” rent discount, or in some cases an increase in rent.

Rent for the 43 units targeted at households earning the median income, about $113,000 a year for a family of four, will drop by an average of $276. At the same time, rent at the 86 units priced for households making 120% AMI, about $135,000 a year for a family of four, will on average stay at about market-rate, according to HR&A’s report.

But a more granular breakdown of rent prices in the study reveals that the 40 one-bedroom units targeted for the top income band will actually see a monthly rent increase of $113, going from $2,564 to $2,676.

“The Transaction claims to be supplying unmet housing demand that will help the City meet affordability targets and support moderate-income households, but a close analysis of the Transaction’s mechanics and definition of affordability reveals only modest affordable housing gains by several measures,” HR&A’s study states.

One major reason for the underwhelming rent savings, according to the consultant’s report, is that families moving into the Oceanaire will be expected to pay 35% of their income as rent. And they will additionally have to pay for utilities, raising their housing cost higher still. Whereas the state and federal government require affordable housing costs, including utilities, to be no more than 30% of a tenant’s income.

“I’ve never seen that approach. It does not line up with the way the State of California or HUD (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development) set affordable rents,” said Phillip Kash, a partner at HR&A Advisors and one of the authors of the analysis commissioned by the city. “These are not affordable units in the normal sense of the word.”

However, Jon Penkower, the managing director of CSCDA, argues that the difference between housing costs being 35% and 30% of a tenant’s income is a “misplaced concern” at the moderate-income level. He said the impact of those percentages are relative to income and location.

“That percentage, 30 versus 35, is a lot different to someone who’s earning $38,000 a year than to someone who is making 120% of AMI,” he said.

According to the HR&A report, the difference in rent between those percentages is on average between $404 to $581 per month.

“When you move it from 30% to 35%, that doesn’t sound like a big deal but we’re talking about telling everybody you’re getting one thing, but actually charging several hundred dollars a month more than what is affordable. And so it is misleading. It sounds like rents are being reduced to affordable levels, but they aren’t. And you’ve got to be sophisticated to catch it,” Kash said.

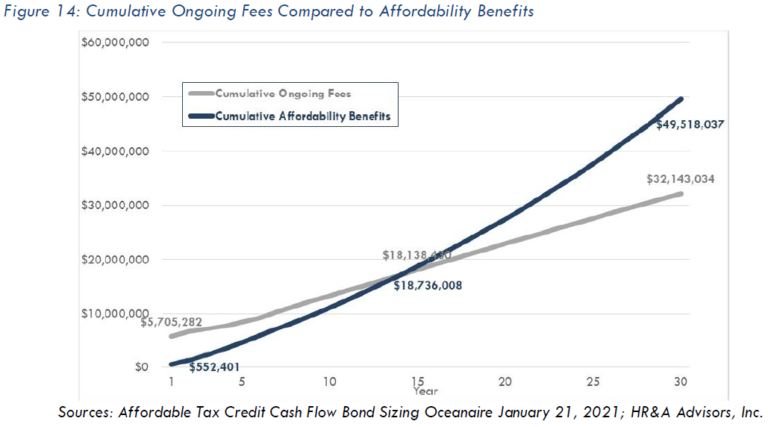

Once the building is fully converted to income-restricted units, HR&A projected that in the first year, the aggregate reduction in rents will amount to $1 million, less than the $1.53 million in property tax that will be lost.

To arrive at the total rent savings, HR&A found the difference between the amount of rent tenants were paying at the Oceanaire in the months prior to its purchase and the income-restricted rents the CSCDA is hoping to achieve.

However, Waterford President Sean Rawson disputes this math, saying aggregate rent savings come closer to $1.4 million when using more current rent data.

“As we’ve come out of COVID, rent growth has been through the roof,” he said. “HR&A were using artificially low rents because it helped further their narrative. And we pointed that out, and they just chose not to use the market rents that we showed them.”

However, a market study commissioned by the CSCDA found that Oceanaire rents prior to the building’s sale were already higher than other similar market-rate downtown apartments.

“There has been some rent growth, I agree with that,” Kash said. “They’re still getting more public subsidy than they’re reducing rent. And we feel very confident that that remains true even with recent increases in market rent.”

Not only will the cumulative affordability benefits always be smaller than the property tax subsidy, HR&A found, but the difference will grow over time.

Penkower, however, claims that rent savings will deepen as the deal matures, eventually overtaking the amount of property tax that is lost.

“We have to fund extensive reserves to get the investors comfortable in buying these bonds,” he said. “There’s extraordinary expense reserves and we have to fund that with bond proceeds. So you can’t just say on day one, why is the first year property tax not equal to the rental savings.”

One of those reserve funds, according to HR&A, holds five years worth of fees for Waterford and the CSCDA, guaranteeing payment “regardless of the Oceanaire’s performance.” The consultants found that these fees were another reason why the rent discounts offered at the building would be limited and inconsistent with what’s usually offered by traditional affordable housing.

MILLIONS OF DOLLARS IN FEES

Part II

In their report, HR&A told city officials that the heavy amount of upfront and ongoing fees to Waterford and the CSCDA involved in the transaction eat into the cash available to provide more affordable units.

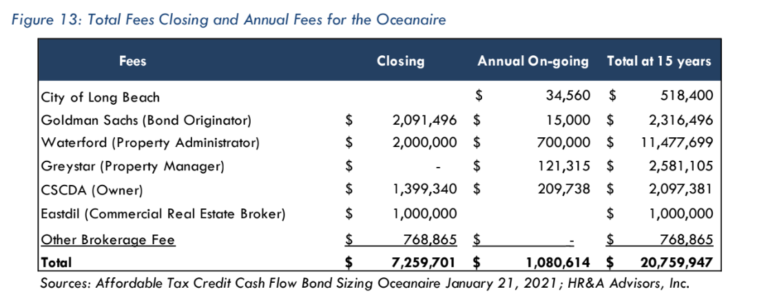

Waterford and the CSCDA received a total of $3.4 million in fees at the close of the building’s sale and will receive a combined $900,000 in annual payments over the course of the arrangement, according to HR&A’s study.

“As a result, in the first 15 years there are $20.7 million in fees to the project proponents. In combination, these fees are high considering that there is neither cash equity nor development risk involved in the Transaction,” the analysis states.

What this means is that neither the CSCDA or Waterford staked any of their own money on the project; there were no building costs and no down payment involved since the bonds fully financed the property’s purchase.

The CSCDA has pushed back on this, writing in a rebuttal to the HR&A study that the fees are “commensurate with any municipal bond issuance of this size. When the City issues bonds it is not free of transaction costs. Moreover, the entities require fees as compensation for providing asset management services and assuming potential liabilities.”

The smaller of the three bonds issued by the CSCDA—a $5 million bond yielding 10% annual interest—was issued exclusively to Waterford.

In simple terms, this bond is an agreement by the CSCDA to pay $5 million to Waterford by 2061, but not before the two larger bonds are paid off. Until then the joint powers authority will pay Waterford half a million dollars a year in debt interest or what HR&A calls “preferred equity payments.”

The return Waterford is getting on this bond is extraordinarily high, nearly double the current interest yielded by municipal junk bonds—the riskiest type of municipal bonds for projects that have uncertain revenue streams and a high chance of defaulting.

Waterford claims that the lavish interest payments are needed to guarantee the company has a financial interest in keeping things running smoothly and protecting the bondholders’ investment.

On top of the interest payments, Waterford will receive a $200,000 annual property administrator fee that inflates by 3% each year, according to the HR&A study.

The bond offering document states Waterford will be responsible for insuring the property and overseeing maintenance—though the cost of these operations will be covered by reserve accounts bankrolled by bond funds. The company will also handle leasing and other administrative and compliance work.

Between the bond interest and project administrator fee, Waterford is set to make at least $700,000 a year off the deal, compensation that is guaranteed “even if the Oceanaire performs poorly,” according to the HR&A study. In total, Waterford stands to make a total of $11.5 million over the first 15 years of the deal without risking a penny.

HR&A argues that with so much of the value created by the deal being gobbled up by fees for Waterford and the CSCDA, there’s little wiggle room left to offer deeper rent discounts.

“These fees reduce the cash available to provide more affordable units. The result is that the on-going fees exceed the affordability benefits for the first 14 years of the Transaction and account for 65 percent of cumulative affordability benefits at year 30,” the HR&A study found.

Ben Metcalf, the managing director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, believes it’s still an open question how to best size the fees in these types of transactions, which only emerged last year. He cautioned that because this financial model is so new and largely unregulated, there is a potential for inflated fees, something cities should be wary about.

“It does feel to me, if I were a city, I would want to make sure that I was getting a minimum level of public benefits, and if the fees did seem excessively high, I would really want to know why and make sure that the amount was legitimate.

“And if it wasn’t [legitimate], I’d want to get my fee lowered so I could put more of that value into lowering the rents,” said Metcalf, who also sits on the advisory board for Catalyst Housing Group, a real estate firm participating in a similar model to convert market-rate apartment buildings into moderate-income housing in the Bay Area

In addition to the Oceanaire, Waterford has entered into similarly lucrative deals with the CSCDA’s Workforce Housing Program to acquire apartment buildings around the state—projects that so far total over 2,000 units.

UP TO $43 MILLION PROPERTY TAX LOSS

Part III

When the CSCDA purchased the Oceanaire it became exempt from property tax since the joint powers authority is a public agency. This is a rare benefit for an apartment building, one that is typically only available to “properties restricted to low income households that provide deeper affordability,” according to the HR&A study.

Because property taxes go toward funding various public entities, only a fraction of the $43 million subsidy the Oceanaire is eligible to receive over the life of the deal will be coming from the city’s coffers. Long Beach will forgo roughly $4 million in property taxes over a 15-year period, the minimum duration of the deal, and up to $7.8 million if the deal lives out its full 30-year term—a hit to the General Fund of about $264,000 in the first year, according to the HR&A analysis. By year 30, that amount would increase to nearly half a million dollars.

City staff wrote in their report that this loss of revenue will “likely effectively require some reduction in services elsewhere.”

If the deal were to go the full 30 years, $35 million in property tax revenue would also be siphoned away from other taxing entities that provide essential services to local residents such as the Long Beach Unified School District, Long Beach Community College, and Los Angeles County.

And while it will take an estimated six years to convert all of the units to income-restricted rents, the project received the full benefit of the property tax abatement from day one.

More broadly, the interest gained by investors buying the tax-free bonds used to purchase the Oceanaire will not be subject to federal and, in some cases, state income tax—a transfer of millions of dollars of public money into private hands. Because the interest from these types of bonds is tax exempt, they are generally most attractive to investors in the highest tax brackets, who have the most to gain from sidestepping tax obligations.

The CSCDA issued three tax-exempt, unrated bonds totalling $139.4 million to cover the purchase price of the Oceanaire, as well as closing costs, capitalization of reserve funds, and millions of dollars in fees to Waterford, the CSCDA, and Goldman Sachs, which underwrote the bonds. During the course of the arrangement, interest and principal payments on the bonds will primarily be paid using rent revenue.

Tax-exempt bonds, also known as public purpose bonds, are similar to low-interest loans government agencies can take out for expensive infrastructure projects that have a broad public benefit. However, instead of going to a bank, a public agency gets the money from investors who buy its bonds. In this case, the CSCDA is issuing the bonds on behalf of Long Beach.

The high-income investors who buy most tax-exempt bonds will collect more than $5 million per year in interest, according to an analysis by Steve Askin of Small World Strategy, a local public interest consulting firm. “If all the bondholders are wealthy Californians, their combined federal and state tax breaks could net them a total windfall of up to $2.5 million per year in state and federal tax savings,” he estimated.

CITY WITHHELD CONSULTANT REPORT

Part IV

During the council’s roughly 30-minute discussion on Feb. 16 preceding the unanimous vote to ratify the deal there was little questioning or concern about the potential for the arrangement to become a boondoggle, despite the stark warnings presented in the HR&A study. Instead, praise for Waterford and the program dominated the conversation.

Councilmember Roberto Uranga called the program a “great experiment” while Councilmember Mary Zendejas bafflingly remarked, “Any housing that is developed is going to help our housing crisis.” Following suit, Vice Mayor Rex Richardson said of the deal: “It makes a lot of sense.”

Only Councilmember Suely Saro expressed any ambivalence about the terms.

“My concern is just the loss in potential property tax revenue with this pilot project,” she said during the February council hearing.

Development Services Director Oscar Orsi responded by saying that concern was part of the reason city staff was recommending the deal only as a pilot program—one that could span up to three decades and potentially cost $43 million in public money.

No councilmember brought up the HR&A study and although it was cited in the city staff report attached to the meeting agenda, Long Beach’s city management chose not to make the document itself public as is typical with other consultant reports relevant to items under consideration by the council.

City Manager Tom Modica defended that decision by saying that the city staff report sufficed and “disclosed the major topics” of the consultant’s study.

“We summarized it just like any time we get reports. Those are public documents, if anyone wants it, they can have it,” he said during a July press conference, referring to HR&A’s report. “There are some concerning things because it’s a brand new program and we outlined what those are but we also recommended that we go forward and do one pilot program.”

However, the city staff report did not divulge the full scope of issues identified in HR&A’s report, namely that the housing affordability created will never be more than the property tax subsidy.

The consultant’s report also found that the the need and urgency for moderate-income housing in Long Beach is much less urgent and critical than the need for lower-income housing.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING FOR WHOM?

Part V

Tenants already living at the Oceanaire who meet the income qualifications will receive rent decreases when they sign a new lease. Current tenants who make too much won’t be displaced, but rather will continue to pay market-rate rents plus a 7% markup until they decide to move, at which point their units will also be converted into income-restricted housing.

Rawson said that since the CSCDA and Waterford took over the Oceanaire, 46 units have been converted into income-restricted housing.

“If you look at the job description of folks that are leasing those units, we’ve got SEIU (Service Employees International Union) field workers, City of Long Beach employees, med techs from the VA hospital in Long Beach,” said Rawson. “These people in the missing middle are all making anywhere from $50,000 to $100,000 a year. And they’re on average saving $400 or $500 a month. And I would tell you, there’s real value in that.”

The term “missing middle” has become something of a buzzword among developers, housing policy wonks, and politicians in recent years. It refers to a gap in the housing market for those who make too much to qualify for low-income housing but make too little to afford market-rate rents.

Mayor Robert Garcia has been especially vocal about creating more missing middle housing, a term he employees often when speaking publicly about affordable housing.

“One goal of mine and of the city’s has been to build affordable housing for what we call the ‘missing middle,’ and that is folks that may not be low-income but still need assistance for housing,” he said during his annual Building a Better Long Beach presentation in 2019.

Cities across the state, including Long Beach, are lagging woefully behind on producing enough housing not only for low-income households but also for those in the moderate-income band.

The state requires cities to periodically conduct a Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA), which quantifies the housing need within each jurisdiction. Long Beach’s RHNA for the period between 2014 and 2021 had a production goal of 1,170 moderate-income housing units. Only 37 have been built so far. The city’s next RHNA cycle, which begins in 2022, sets the target of moderate-income housing construction even higher, at over 4,000 units.

However, due to the way housing units are counted for the RHNA, the converted Oceanaire units won’t count toward Long Beach’s moderate-income housing tally, according to HR&A.

The major reason for the shortfall of middle-income housing is because building for this income bracket does not typically provide enough return on investment to make it attractive to developers. State and federal subsidies, which can sweeten the bottom line, are in short supply and are generally directed at projects for lower income households.

“There’s no funding source, zero, that has been able to help finance the creation of moderate-income housing. And that’s really been to the dismay of those middle-income households. They need housing as well,” said Rawson. “I agree, you need deeper affordability. I totally agree. But there are funding sources for that.”

This is the problem the financial model applied to the Oceanaire is trying to solve. But not everyone agrees that creating moderate-income housing should be the priority, especially when public subsidies are involved.

“Their argument will be that other programs are serving the low-income need. That’s a pretty ridiculous argument. There’s 10s of 1000s of [lower-income] households in need. And we’re doing hundreds of units [of low-income housing], which is nowhere near that,” said Kash. “It’s not that there’s no need for moderate-income housing, it’s just nowhere near the highest priority.”

He said only about one in 20 renters in Long Beach earning the median income can’t afford rent, compared to more than half of households that earn less than 80% of the median income.

The HR&A report also noted that “the housing cost burden for moderate income households in Long Beach is much lower than in the rest of Los Angeles County or California more generally.”

A market study commissioned by the CSCDA included in the bond offering document, shows that the majority of renter households in downtown Long Beach have incomes under $50,000—households that would not be able to qualify for an apartment at the Oceanaire. However this majority may soon vanish, as the market study also found that lower income renters are trickling out of the downtown area and renters with higher incomes are moving in.

Local tenant advocates also questioned the decision to pour public money into housing for a demographic that isn’t generally struggling to ward off displacement or even worse, homelessness.

“It strikes me as an incredible diversion from the real need,” said Neal Richman, a board member of local tenant advocacy group Long Beach Residents Empowered (LiBRE) and a former urban planning professor at UCLA. “There is still no fund for low-income housing in the city. The housing trust fund is not funded and there is no pot of money for low-income housing.”

Only the studio apartments set aside for the lowest income band at the Oceanaire will be lower than the average rent for a downtown apartment, which is currently at $2,093 a month, according to a report from the Downtown Long Beach Alliance.

Both Rawson and Penkower see it differently and say the Oceanaire offers luxury amenities, which will be a bargain at the prices now being offered and argue that a mix of affordable housing types is vital to addressing the housing crisis and lifting the local economy.

“The program gives [tenants] additional discretionary income that helps local businesses. You know, people will have more disposable income. So that goes back into businesses and downtown Long Beach. In addition to that, it helps households save for their first down payment of their first house,” said Rawson.

But will there be enough families of four making $112,000 a year that are willing to pay over a third of their income to rent a three-bedroom unit at the Oceanaire? Bond offering documents disclosed the possibility that it could be a tough sell: “There can be no assurance that the Authority can meet the targeted income restriction categories due to the availability of qualified tenants for each income restriction category.”

And if not enough moderate-income tenants bite, the Oceanaire’s door could be opened to higher income tenants to make sure units don’t sit empty and debt obligations are met.

Rawson said there’s little chance of this happening and that such a situation “shouldn’t even come into play.”

“Don’t you think that there’s a tremendous amount of pent up demand at that 80% to 120% AMI level to live in a class A building in Long Beach?” he said.

So who is in charge of making sure income restrictions are being met? The CSCDA has promised to reimburses the city about $35,000 for “limited” staff time dedicated to monitoring the affordability of the building, according to HR&A.

But even if the city were to get wind of non-compliance, Penkower said there is no direct mechanism for the city to enforce the affordability restrictions. According to a bond regulatory agreement, the CSCDA and Waterford will ultimately be responsible for making “best efforts” to meet affordability restrictions—the same entities that are also deriving fees from rent revenue—and will annually report to a bond trustee.

This lack of local oversight was an issue identified by city staff in San Jose in their report recommending against a similar deal: “There are no other funders, or financing participants, that can incent compliance. There is no regulation that clearly requires adherence to income restrictions within a given timeframe.”

WATERFORD HAS GIVEN OVER $126,000 TO LOCAL POLITICIANS

Part VI

Waterford is one of the largest property owners in the city; their $1 billion portfolio stretches from California to Arizona and locally includes the City Place retail district and the One World Trade Center complex. In their presentation about the Oceanaire transaction to the council, city staff said Waterford had a “positive track record” in Long Beach. A few minutes later, Councilmember Stacy Mungo called the company “a trusted partner of the city.”

But in the years before city and state renter protections were put in place, the company was busy snatching up run-down apartment buildings in Long Beach in order to renovate them and hike up the rents, sometimes making millions by flipping them, and often displacing existing low-income tenants of color in the process.

That’s what long-time tenants at a multi-family apartment building on Cedar Avenue accused Waterford of doing in 2017.

“These are our homes and they just look at it as business properties where they can make more money,” Kimberly Navas, one of the tenants who was ultimately displaced from the Cedar complex, told us at the time.

Earlier this year, Waterford was one of the parties that settled a lawsuit brought by the Cedar tenants for $2.7 million, according to court documents. The tenants alleged that Waterford, which bought the building in 2017, as well as the prior owner, failed to properly maintain the property, causing the residents to suffer illness, injury, mental stress, emotional suffering, loss of income, and property damage.

“That has nothing to do with the Oceanaire program. So let’s be very clear there,” said Rawson. “We bought that asset from the owner, who got sued as well, and was running the building in squalor. We stepped in and put money back into the asset. We got sued for habitability issues, but to be very clear, we were the ones that fixed it. And we got caught up in that lawsuit with the previous seller.”

Waterford also evicted tenants at an apartment complex on Pacific Avenue in 2018, including an 81-year-old man who had lived there for nearly 30 years.

Some have questioned why elected officials approved of a deal that uses public subsidies to help line the pockets of a company with such a checkered past in the city.

“While the Mayor and council members speak of equity, they choose to deeply subsidize a company and its owners who are grievously disinvesting in our communities,” said Richman of LiBRE. “Is it a surprise that the division between rich and poor is intensifying in Long Beach?”

The Newport Beach company has acquired at least 15 multifamily apartment buildings in Long Beach since 2015, according to its website.

Meanwhile, the company and its executives have become major players in local politics. So much so that Rawson, Waterford’s president, co-hosted Zendejas’ $125-a-ticket re-election campaign kickoff event in June at Portuguese Bend.

At the event, local tenants and organizers from the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) Long Beach attempted to confront Zendejas about the substantial remodel loophole in the state’s 2019 Tenant Protection Act. However, organizers say Zendejas’ staffers shooed them away.

Rawson also sits on the board of directors for the Long Beach Downtown Alliance and was invited by former Mayor Bob Foster to be part of the city’s coronavirus Economic Recovery Advisory Group last year.

Waterford, along with Rawson, the company’s co-founder John Drachman, their wives, and Scott Scharlach, a Waterford executive based in Arizona, have donated $126,850 to current Long Beach officeholders since 2015, with the mayor being the largest benefactor of their largess, according to campaign finance records.

“I will tell you that we are active in local politics. I live in Long Beach, I love the city, and I’m a believer in good governance and good politics. And like any stakeholder, no different than all the who’s who in Long Beach, we are active supporters of people that we think are good elected leaders. And that’s it,” said Rawson.

Waterford and individuals tied to the company have spread $85,550 across virtually every political bucket the mayor controls, from his officeholder account to his Measure A and B campaign to his Robert Garcia for Lt. Governor 2026 committee.

In fact, Garcia’s Lt. Governor campaign received hefty donations from the Rawsons, the Drachmans, and Scharlach in the months following the council’s approval of the Oceanaire deal. On March 13, Drachman gave the campaign $8,100, followed by another $8,100 from Rawson on April 1. Then it was the wives’ turn to chip in: Laura Drachman and Jennifer Rawson donated a combined $15,600 on May 27, campaign finance records show. That same day Scharlach dropped $8,000 into the coffers of the mayor’s Lt. Governor campaign.

In 2019, Rawson and Drachman told the Long Beach Business Journal that Garcia was someone “whose vision of the city aligns with theirs,” citing their desire to be part of a societal shift of “younger professionals moving to urban cores with access to the coast.”

Asked whether he believed the city got a fair shake in the Oceanaire deal, the mayor said he wasn’t familiar with the details. It was his first public remark on the matter.

“Staff actually recommended that project and I think it was passed unanimously by the City Council,” Garcia said. “I don’t know the details of every single project.”

While Garcia was behind the dais when the council voted on the Oceanaire item, the Mayor does not vote nor needs to sign resolutions passed by the council—though he does have veto power.

But the mayor was not the only one to benefit from Waterford’s political generosity. Richardson’s political campaigns have received over $29,450 in contributions from Waterford and its executives. The vice mayor’s Lift Up Long Beach Families ballot measure committee, used to support Measure US last year, has been the main recipient, receiving a total of $27,000 in contributions between 2019 and 2020.

Richardson is listed as the only principal officer of Lift Up Long Beach Families, meaning he controls the committee’s spending.

He did not reply to a request for comment.

Zendejas, a first-term councilmember currently seeking reelection, has so far received $2,150 in political contributions from Rawson. He also gave the maximum of $400 to Second District Councilmember Cindy Allen’s 2020 campaign two years in a row (in fact Rawson donated $800 in 2020, triggering a refund of one of his $400 donations that year). In June, Allen awarded Waterford—the same company that was party to a $2.7 million settlement paid to displaced tenants—with a certificate of recognition for providing “essential housing.” Allen represents the district in which the Oceanaire resides.

“If we are going to solve our housing crisis, we must look to new ideas. There are many people who work downtown, who support the community—not only service workers, but also teachers and firefighters—and it’s very hard for them to live close to where they work due to rising housing costs,” Allen was quoted saying in a Waterford news release. “Now at Oceanaire we are able to provide quality housing at an affordable rate.”

Neither Zendejas nor Allen responded to a request for comment.

Lobbyist activity reports published by the city show that Alex Cherin, a partner at communications firm Englander Knabe & Allen was lobbying city officials on behalf of Waterford between July 1, 2020 and June 30, 2021. And while Garcia claimed not to know the details of the Oceanaire deal, he was one of Long Beach officials listed in the reports as a lobbyist contact. Others include Richardson, former Councilmember Jeannine Pearce, City Manager Tom Modica, and Deputy City Attorney Rich Anthony.

Englander Knabe & Allen’s founding partner, Harvey Englander is the uncle of disgraced former Los Angeles Councilmember Mitch Englander who was recently pled guilty to obstruction of justice in a case involving a pay-to-play scheme with developers.

Cherin—who himself has given a fair share of donations to Long Beach politicians—spoke during the council hearing just before the Oceanaire deal was approved.

“I think it checks a number of housing boxes and policy boxes for the city, some of which were recently addressed in the city’s housing studies last year,” he said. “So I think this is incredibly consistent with where the city wants to head long-term.”

No other members of the public spoke on the Oceanaire deal, which was the final item heard by the council during the nearly four-hour meeting.

According to campaign finance forms, Cherin has contributed $9,600 to current elected officials since 2014, including $3,700 to Richardson.

“It goes beyond a conflict of interest. It’s literally a direct profit line. The city money that goes into the deal makes its way into the bank accounts of the campaigns,” said Jordan Doering, a member of the DSA Long Beach. “It’s insane that there’s no oversight at all.”

BAILOUT FOR DEVELOPER?

Part VII

The seven-story Oceanaire was developed by Lennar Multifamily Communities and completed in August 2019. The homebuilding giant sold the property less than two years later.

Some have suggested that the sale of the Oceanaire to the CSCDA was, in part, a bailout for Lennar.

When the idea to convert the Oceanaire into moderate-income housing was first brought to the City Council in October, high-end apartments in the region were seeing slumping rents and high vacancy rates due to overproduction and COVID-19.

“This opportunity wouldn’t exist, but for the fact that [luxury developers] made mistakes and bad assumptions,” said Matt Schwartz, the president and chief executive of the California Housing Partnership, a San Francisco-based nonprofit that’s been looking into these types of deals. “And so I think the last thing we want is localities and taxpayers bailing out market-rate developers who made some bad calls.”

However, Penkower said these projects are not bailouts and that Lennar would have sold the Oceanaire regardless of the CSCDA’s program.

“The merchant builders, like Lennar, and these other big builders, that’s their business model. They build, lease up, and they sell. They have an equity partner and they want out. They want their money back. So they’re not in the business of holding them,” he said.

But as far back as 2015, Lennar announced it had pivoted its business model to building and holding luxury apartment properties long term. In a press release that year, the company announced a new billion-dollar venture fund that would invest in Lennar Multifamily Communities, the subsidiary that built the Oceanaire. Lennar said the fund’s purpose was “developing multifamily communities and then holding those communities in a portfolio long term for cash flow.”

Lennar did not return a request for comment.

Rawson also disputed that the deal was a bailout, saying the accusation doesn’t make sense because the “multi-family markets are on fire right now.”

But even into the early months of this year, the market for luxury apartments was still reeling from the economic effects of the pandemic.

Lennar reported a loss of $900,000 in their multi-family apartment business during the first quarter of 2021, according to an earnings report.

Prior to the pandemic, hopes had been high for the Oceanaire. A spokesperson for Lennar told the Long Beach Post in February of last year that the company expected to see the Oceanaire’s capacity at over 90% by the summer of 2020.

A year later, HR&A projected that the Oceanaire’s occupancy rate in February 2021—the same month the council voted on the deal—would dip to 68% after trending down in the prior months. That’s far off the mark of stabilized occupancy—a real estate term meaning that enough units in a given building have been leased up to generate a reliable cash flow. An occupancy rate of at least 90% is typically considered stable and the lower that number, the harder it is to reliably appraise a property’s value.

The market analysis commissioned by the CSCDA found that in December the Oceanaire had the lowest occupancy rate compared to three similar luxury apartment complexes in the downtown area also completed in 2019.

In March, the CSCDA purchased the property for $122 million.

“There was no real incentive here to negotiate a good sale price. There’s actually every incentive to overpay because they’re getting 100% financed on it,” said Kash.

A POTENTIAL HOUSE OF CARDS

Part VIII

While Waterford and the CSCDA frontloaded their compensation in the form of fees and bond interest, the public sector, on the other hand, will be the last to get paid out, leaving its investment—the tens of millions of dollars in forgone property tax—much more exposed to the whims of the market and asset depreciation, according to the HR&A study.

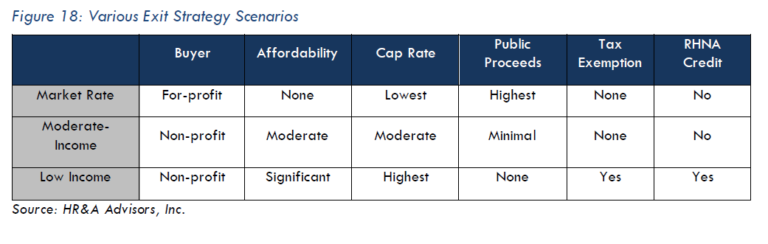

After 15 years, the city can take ownership of the Oceanaire and exercise an option to force the CSCDA to sell the property on its behalf. However, triggering this option is contingent upon the proceeds from such a sale being able to cover any outstanding debt and fees, a balloon payment that could potentially total over $100 million, according to HR&A. Any leftover funds can then be claimed by Long Beach to replenish lost taxes, and finally as extra revenue.

But whether Long Beach will recoup the millions in lost property tax, much less gain any profit, will depend on market conditions and how much outstanding debt remains at the time of sale.

“The City’s potential proceeds are at the bottom of the sale proceeds distribution waterfall, leaving the City open to significant market risk at time of sale or refinancing between the 15th and 30th years,” notes the HR&A analysis. “Small variations in rent growth and vacancy have the potential to dramatically reduce the surplus sale proceeds from the Transaction at year 15.”

City staff said it’s unlikely Long Beach would opt to sell the Oceanaire at year 15 because in order to pay off the balloon payment, the sale price would need to be maximized, meaning the building’s affordability restrictions would likely need to be lifted. Even after 30 years, the city says it expects there will still be outstanding debt at which point the Oceanaire would need to be sold to satisfy those obligations.

Because the bonds are not expected to be fully paid off by year 30, Kash says that the tail end of the deal could put the city in the unfortunate position of having to choose between preserving affordability or forfeiting the rent discounts in order to get the highest sales price possible.

The HR&A report lays out various exit strategies that the city would be left with after the 15-year mark. The Oceanaire could be sold to a for-profit buyer, an option that would yield the highest sale price, but would erase the moderate-income restrictions. Alternatively, the building could be sold to a non-profit buyer, which would preserve or even deepen rent discounts, though that would yield little to no sales proceeds for the city, meaning lost property tax would likely not be recovered.

“Knowing exactly how the markets are going to go over the next 15 years is beyond our ability and anybody else’s. There are reasonable market situations where this doesn’t actually work at exit,” Kash said.

City staff also acknowledged this possibility in their own report: “The potential financial benefit to the City is highly sensitive to the rent growth assumptions … As a result, there are likely situations where the City and other taxing bodies do not recover foregone property tax or make a profit.”

Yet those who pushed for the deal have all but guaranteed that the $43 million in tax subsidies will be recaptured at exit, even confidently projecting that the city will profit handsomely, thus presenting the arrangement as a no-brainer.

“While in the short term the city of Long Beach will relinquish its share of property tax revenue from this property, the long-term opportunity is for the city to sell the property at a 30-year point and benefit from significant sales proceeds that will provide Long Beach with a significant return on its investment,” Rawson wrote in an editorial published in the Long Beach Press-Telegram in March.

Penkower said that a scenario where the city doesn’t recover lost property taxes would be “inconceivable.”

The CSCDA’s market projections state that in 30 years, the building will double in value and that Long Beach will make out with over $150 million in proceeds if the property is sold. That’s roughly 15 times the city’s initial investment.

“It’s no different than a house or an apartment complex. You look at the long term value over 30 years relative to what the city is giving up in property tax revenue, I will tell you it’s monumental how much equity reverts back to the city once these bonds are paid off,” said Rawson.

To arrive at such a high rate of return, the CSCDA is assuming that there will be a 3% annual rent growth rate over each of the next 30 years.

But looking at the last 20 years, a rent growth rate that high was only reached or exceeded from 2015 to 2018, when Long Beach was in the midst of its most recent building boom, according to the HR&A study. Even city staff in their report acknowledged that the CSCDA’s market assumptions are “very aggressive.”

After crunching the numbers, HR&A calculated that if the rent growth rate falls just 1% below the market assumption put forth by the CSCDA, $28 million of the $43 million in tax subsidies will remain unrecovered if Long Beach opted to sell the Oceanaire property at the 30-year mark.

Penkower disagrees, saying that while the bond principal likely wouldn’t be paid off in 15 years, he assures that by year 30 the city should expect to gain most, if not all, of the proceeds from selling the Oceanaire.

“If the project is producing excess cash flow over time, as it’s anticipated to do, you just accelerate the repayment of bond principal. So it’s paid off early. The city, if they wait until the end, they will not have to pay off any remaining debt.”

But HR&A’s study found that the bonds are not designed to be paid off even after 30 years.

“Neither the Series A nor the Series B Bonds are fully amortizing, implying that under any scenario there are always debt obligations to be repaid at the 30th year,” the consultant’s report states.

Another unorthodox aspect of the deal is its financing structure.

In contrast to how multifamily properties are traditionally bought on the private market, where a loan is taken out to finance 70% to 80% of the purchase price and the remainder is covered by a down payment, the amount of debt tacked on to the Oceanaire exceeds the cost of the property. Some experts say that going around the traditional lending standards for multifamily properties and starting out underwater means that if things don’t go according to the highly optimistic market forecasts used to underwrite the bonds, the whole thing could quickly become a house of cards.

But Rawson said critics are misrepresenting the mechanics of the deal, noting that there are vast reserve accounts to cover unforeseen expenses. However, it’s important to note that these reserve accounts are made up of borrowed bond money that will need to be repaid at some point, meaning that the whole arrangement still relies on rents going up just to fully pay off the interest on the bonds.

However, Rawson says that the financing structure has been thoroughly vetted by the major financial institutions that are purchasing the bonds.

“Do you think investment banks like Blackstone, Citi Group, Franklin Templeton, Goldman Sachs, Stifel, PIMCO would be investing in buying these bonds, these assets, without doing a thorough credit review?” Rawson said. “CSCDA is not going to do anything to disparage their reputation, their standing not only in the government community, but also the investment community.”

But in a financial document detailing the terms of the bond sale, investors were warned about the precarity of this arrangement: “No assurances can be made that the Facilities will generate sufficient revenues to pay maturing principle of or Redemption Price of the interest on the Series 2021A Bonds and the payment of the Operating Expenses of the Facilities.”

The 666-page document further states that the financing structure and the high amount of fees “limit the Project’s flexibility to accommodate unforeseen capital expenses, leasing issues, or other changes in market conditions. Furthermore, it is not clear that the structure can accommodate major maintenance and renovation costs likely required after the first ten years.”

And with such little cushion between market rents and the rents at the Oceanaire, HR&A’s study suggested that if the rental market takes a hit, rent prices at the Oceanaire could end up at the same level as neighboring buildings in downtown, erasing any incentive for prospective tenants to move in, which could spell trouble for the project.

“In the likely event that market rents grow more slowly, a large share of the affordable rents will not be competitive, creating a cash flow issue, eroding affordability benefits and reducing the public fiscal benefit,” the consultant’s analysis says.

And what if there’s a full on default and the bondholders foreclose on the Oceanaire? Penkower says that the possibility of that is “remote.”

“You would have to have a complete collapse of the multifamily landscape in a particular community,” he said. “ I mean, like a 1920s-type recession.”

In such a scenario, not only will the bondholders lose their investment, but there’s also the question of whether the city would have to come to the rescue, according to Metcalf.

While the city is not legally liable for the bond debt, it is partly responsible for making sure its up to code.

“Is there a scenario whereby the property goes into default, the bondholders lose their shirts, but somehow the city is then politically expected to come in and replace the roof? I don’t know,” he said. “I think that’s a risk that cities would need to make sure that they’re comfortable with.”

The reputational risk to the city should the project default was another issue that city staff in San Jose raised as a reason to oppose a similar project: “While it is true that the City is not directly liable for the debt, it would join a JPA that would issue non-rated bonds subject to Federal securities laws and antifraud provisions and would be associated with any bonds that fail or encounter difficulties.”

Kash said that the risky nature of the financial structure used to purchase the Oceanaire has elements reminiscent of the subprime mortgages that brought down the economy in 2008—only instead of homebuyers, it’s municipalities that are having the wool pulled over their eyes.

“Everybody’s got a financial interest in not pointing out how flawed this is,” said Kash. “At the end of the day it is eating a lot of public funding and does little to nothing to improve affordability. Which is disappointing.”

Copyright © 2025 FORTHE.org. All rights reserved.