Long Beach’s Land Use Element: Bad Policy, Bad Process, Bad Intent

13 minute readOn mobile devices, timeline is best viewed in landscape mode.

Long Beach’s revised Land Use Element (LUE) is up for City Council’s approval this Tuesday. Organizations representing single-family neighborhoods will attend to oppose the plan. Over the past year, their interests have enjoyed the largest voice in amending the maps that constitute the City’s new land use guidelines, culminating in a vision that, despite their best efforts, is still not regressive enough to earn their support.

The current Land Use Element, like the 2012 Downtown Plan, shows us which communities have had their perspectives heard in our city’s politics, and which have not. In a short amount of time, the Downtown Plan has forever altered neighborhoods — and not in a merely aesthetic way. Our people are being pushed at this moment into deeper poverty, having to accept crowded conditions, long-term instability, and other precarious living situations. Many have already been forced to leave Long Beach entirely. If passed this Tuesday, the LUE will worsen our housing crisis.

The situation suggests renters’ advocates have no choice now but rent control, when perhaps before, with a truly democratic process, there could have been an equitable solution for all.

Bad Policy

Beacon Economics, an independent research firm, released their report on the LUE last month, and it held no sympathy for the position the City has put itself in — or, rather, the position it has forced its poorer residents into. Looking at five different regions — the United States as a whole, California, New York state, Los Angeles County, and Long Beach — the report concluded “Long Beach was the only region where housing stock decreased between 2010 and 2016…” [1] Of myriad other California cities the report analyzed, Long Beach also had the highest percentage of overcrowded units, especially among those deemed renter-occupied.

Such conditions contribute to depressing news for Long Beach’s future. From 2009 to 2016, our city suffered a net-loss of 4,300 housing units with underage children [1] — a tragedy, that does not quite reach irony, given what single-family neighborhood advocates claim to be protecting in their fight against development.

Families are indeed under attack; but we need to rethink who, and what, is attacking them. In Long Beach, that must start with a hard look at which families we now consider worthy of ascending to the status of victim. The current version of the LUE wants to make space for 3,900 net residential acres, but that includes the loss of nearly 1,000 acres of low-density multi-family housing, to be replaced largely with single-family units [1]. This will involve the direct displacement — rather, replacement — of many families. Eighty-eight percent of the total acres to be added are reserved for single-family use [1].

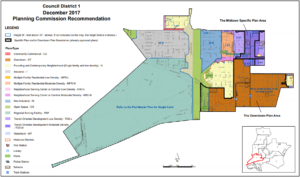

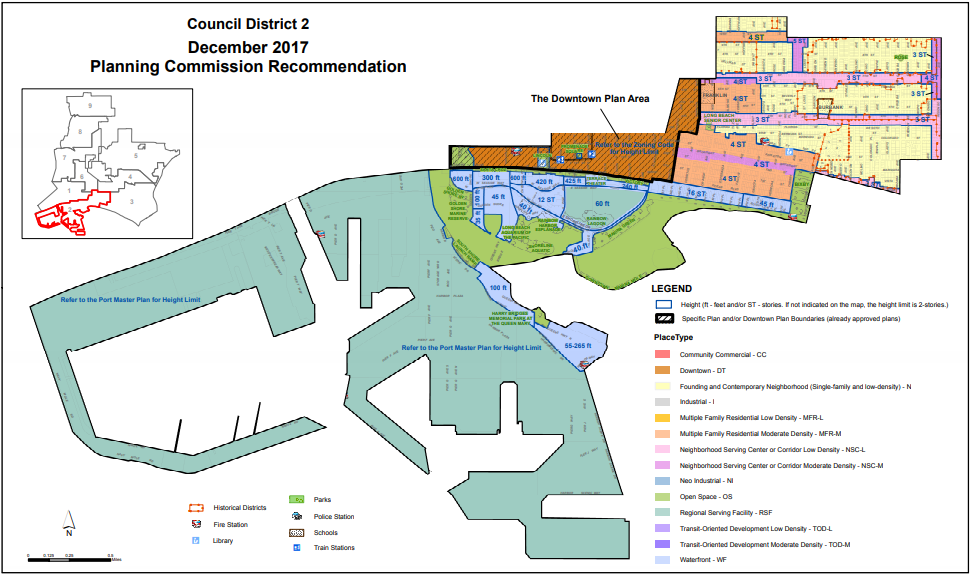

The LUE under consideration this Tuesday will, on the whole, effectively shrink our city. Even Council Districts 1 and 2, where Downtown Long Beach is located, reserve more land for single-family units at the direct cost of denser, multi-family developments. [1] “Overall, seven out of nine Council Districts intend to displace low-density multi-family spaces in favor of single-family spaces.” [1]

District 1 is a prime area for dense, multi-family, affordable development, yet the current LUE proposes to place here more single-family units.

The taking of valuable land for inefficient, low-density development is not a policy designed for housing people. It is explicitly designed to restrict access to Long Beach — all of Long Beach: its parks, bikeways, libraries, schools, music, arts, culture; even its beaches and sunshine.

Density is a natural progression for valuable land. When land becomes worth more, development, unless consciously stalled, becomes denser. That’s because land value signals to people what areas are desirable, and therefore what areas can sustain investment. It’s also because as land becomes more valuable, it of course becomes more expensive. Therefore entrepreneurs, artists, politicians, families, and so on, are all encouraged to do more with less space. This drive towards efficiency also cuts costs for municipalities by grouping people closer together, allowing more convenient provisioning of services, schools, roads, parks, etc. In the resulting convergence of peoples and passions, we are gifted the beautiful, organic, breathing structure of a city.

Privileged homeowners working with government power to cut this story at its head cannot destroy all that land value; they can only hoard it for fewer and fewer hands. This is directly what private collection of land value dictates of human behavior, and this is precisely the process by which parks, bikeways, libraries, schools, music, arts, and culture become weapons against the peoples who have created them.

Altogether, the Beacon report claims the current LUE will “drive rents higher, push vulnerable residents out, and ultimately stifle economic growth.” [1] Their grim, but very real, assessment reflects the most-recent proposed maps, which the City released in January. They differ from the original maps proposed last year because in that time, through various public meetings and private conversations, the LUE has been successfully challenged and altered by single-family neighborhood advocates, leaving us with the counter-productive plan outlined above.

Bad Intent

Of course, the plan is only counter-productive if we assume Long Beach would like to encourage economic growth, maintain manageable rents, and keep vulnerable residents in their homes. The public meetings on the LUE unfortunately displayed the crude, observable fact that many of our residents simply possess zero compassion for whether or not vulnerable residents stay.

I attended one of those meetings last year. About halfway through, a middle-aged gentleman finally got his turn at the microphone and noted, “If you can’t afford to live here, don’t come here.”

Applause filled the white tent the City had put up to shelter the packed crowd. It was one of the loudest moments of the evening. As matter-of-fact as segregating human beings based on economic status seems to be in our social conscious, it derives from an ideological faith in private property, a practical faith in exclusionary zoning, and a fearful desire to privatize the results of progress we all contribute to.

Other comments that night and elsewhere reflected hatred for the notion that Long Beach might become a sanctuary city. Similar experiences have been documented elsewhere [3]; though if you wish to hear and see it for yourself, come out this Tuesday night to city hall.

A Facebook page opposed to the LUE advertises this Tuesday’s City Council meeting, encouraging its members to attend.

Voices like these have helped compose this alternate vision for our community — one imbued not with the urgency of ongoing displacement, but with the fearful drive to keep Long Beach great.

The City has acquiesced to these fears every step of the way. After the series of public meetings last fall, the maps were changed. One of the primary complaints of those who have helped shape the LUE during this period is that it would ruin single-family neighborhoods by bringing more crime. The culprit? Density.

Though the idea that density leads to higher crime rates is a myth [4], it is also sadly common. Crime is more directly a consequence of income and investment inequities, not population density as such. The confusion comes from how we associate density with poverty. To the extent such an association is correct, it would not imply we should reduce density, but that we should reduce poverty; and one of the starkest income and investment inequities in America, and Long Beach, today is housing, which suggests we should build more of it. Yet every amendment to the Land Use Element thus far has moved in the opposite direction.

“The revised maps reflect a reduction in density of 686 acres…” reads the City’s November press release after modifying the maps in concert with public comments [5]. The acreage lost from this initial change was about one square mile. As of the 2010 Census, Long Beach’s current population density per square mile is just over 9,300 [6]. Last month, responding to the same concerns, the City sliced the proposed maps by another 98 acres [7]. Every sacrifice in acres is a loss of future homes.

City Manager, Patrick H. West, noted, “It is clear from the community input we have received that changes to the proposed maps were necessary.” But here “community” means “homeowner”, and that translation clearly shows in which communities the City has chosen to privilege with preservation. “Forty-four percent of the City’s land is comprised of single-family neighborhoods, which will see no changes under the revised maps,” the Long Beach Business Journal reported in November [8].

Perhaps the worst stain in this sullied process, however, came in January. Robert Fox, who has emerged as a leader in the fight against the LUE, had a private conversation with Mayor Robert Garcia, after which Fox cheerfully announced he was not running for the Mayorship against Garcia this April. As reported by LBReport.com [9], Fox wrote that this clear quid pro quo was done with a wink that the Mayor reaffirm his opposition to rent control — which may reach Long Beach voters this fall — and a nod that he also arrange exclusive roundtables with the Council of Neighborhood Organizations (CONO) to discuss the LUE. Fox is CONO’s Executive Director.

Garcia has already come out against rent control [10], and the roundtables took place over the last month, leading up to this Tuesday’s vote. LBReport.com managed to gain access to one of the discussions, writing:

“Mayor Robert Garcia’s office sent invitations to what it called a private invitation-only “roundtable” discussion of the Land Use Element (LUE) with about 8-12 fifth Council district community members… most if not all selected with the assistance of Robert Fox…” [11]

Tomisin Oluwole

Dine with Me, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inchesClick here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Despite the Mayor’s general reputation as a progressive, this process seems to have no concern for our most vulnerable communities. Based on Fox’s influential tugging of the Mayor so far, I assume any further changes to the LUE will empower regressive voices, and include even more reductions in density. At the least, I can confidently state that this final version will not reflect the perspectives of those who do not own a home.

An anti-LUE coalition member speaking during public comments at an LUE workshop held by the city on October 18 at Scherer Park.

Bad Process

Long Beach is a majority-renter city, and it is thus clear from the consistent downsizing of the original maps that the process to compose the Land Use Element has not been democratic enough. By qualifying this process as a democratic failure, I do not mean that there were no public meetings — there were. I mean the process has specifically suffered from at least three large faults.

First, the private meeting between Fox and Garcia remains very problematic. Even if technically legal [12] — which is not, by the way, a phrase meant to shield us from ethics — the meeting still reveals the privileged amount of access some groups in our community have to elected officials.

Second, the subsequent series of CONO/Mayoral roundtables also granted special access, and did so in the closing weeks of this conversation, thus leaving unequal time for other communities to respond.

And third, much more deeply, we have to accept that not all communities in our city are currently as organized, or as monied, as neighborhood associations, but that does not mean they should receive less of a voice.

Given the large disparities in access to public institutions generally, and the specific differences in privilege between the home-owning and renting classes, the onus is not on underprivileged communities to show up one weeknight to a forum. As much credit as the City deserves for holding such forums, it cannot ever be enough. The responsibility must be affirmed by our public officials, and the community at-large, to actively seek a wide range of perspectives, and to more consciously create space for those perspectives to be heard in public discourse. The burdens here must be placed on those who enjoy better access to open up that access to others, and to do so patiently, earnestly, and with love.

A plan that made more space for the concerns of our majority-renter communities would focus on a dramatic increase in market and sub-market rate housing. It would include a vision of jobs, clean air, and transit-oriented development. It would resiliently strive to keep Long Beach affordable and accessible for the very diverse peoples the City, in other ways, celebrates.

Page 12 of a draft of the Beacon Economics report highlights some specific contradictions between the City’s own stated goals and the currently proposed LUE. Click to see.

A more cohesive and compromising LUE would focus dense, multi-family development along high-traffic corridors — something the City originally stated it wanted to do [2], encourage mix-use residential-commercial in areas already zoned for business, construct dense, but more affordable units Downtown, and find a clever way to recover some of the increase in land values that up-zoning brings, thus not allowing the developers or landowners of these specific plots to take off with the windfall gains that the City provides. All this could be done while still respecting single-family neighborhoods.

But the current LUE is narrow-minded, uncompromising, and unfair. It even plans to alter industrial and commercial zoning for single-family use [1], suggesting it was informed by people who do not need to care about our city’s lack of jobs. The current LUE will stall economic growth, exacerbate Long Beach’s housing crisis, and fail to prevent the ongoing, tragic displacement of its renters. It is unfortunate the plan has been amended largely in exclusive conversation with neighborhood associations — representing homeowners and property managers, not renters — and that it therefore stumbles to its March 6th finishing line a tired and empty promise.

Whether it passes or not, the aggressive dulling of the Land Use Element over the past year represents a victory for those with equity in our system of private property in land, and it fails to care enough for those who possess merely a stake in the future of this city, and not in its towering rents.

Featured timeline by Kevin Flores.

Sources:

[1] https://downtownlongbeach.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/2018.02.16_DLBDCReport_Final-1.pdf

[3] http://www.longbeachize.com/tensions-land-use-element-bring-worst-long-beach

[4] http://www.hcd.ca.gov/community-development/community-acceptance/index/docs/mythsnfacts.pdf

[5] http://www.longbeach.gov/press-releases/city-releases-revised-land-use-element-maps/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_Beach,_California

[7] http://www.longbeach.gov/press-releases/city-releases-revised-land-use-element-maps2/

[8] http://www.lbbizjournal.com/single-post/2017/11/10/City-Releases-New-Land-Use-Element-Maps

[9] http://www.lbreport.com/news/jan18/fox2.htm

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org