The Downtown Plan: 10 Years of Rent Hikes & Displacements

by Kevin Flores | Published January 12, 2022 in Journalism

13 minute read"The thrill of competing for funding, pushing through plans, seeing spectacular architecture rising from the soil, or contributing to favourable statistics on investment, population, local GDP, etcetera can be far larger than the search for democracy, equity and diversity in the city.”

It was the day before Halloween, 2015: a sunny, cloudless autumn day, not atypical for Long Beach. On the southeastern end of downtown, at Alamitos and Ocean, a gaggle of local reporters, city functionaries, and business leaders crowded into a construction hoist as they readied to ascend 18 stories to the roof of a nearly-completed luxury apartment tower. In cellphone footage of the ride posted online there’s a visible giddiness among the group, as if they had just been strapped into a carnival ride.

“It’s a new Long Beach, it’s a great Long Beach. You just look around and feel it,” proclaims Harry Saltzgaver, the executive editor of The Grunion.

“I’m pretty excited,” says Mark Taylor, then the chief of staff for Mayor Robert Garcia. Moments later, the construction workers draw down the grated metal doors. Liftoff.

The camera captures the surrounding mid-rises as the group travels above a seaside downtown of serviceable apartment buildings that become smaller and smaller in the distance. The camera turns to the tower’s half-constructed floors as they pass by, giving a glimpse of exposed beams and pipes before the hoist slows to a stop.

“Holy smokes, we’re here,” someone inside the lift exclaims. The doors open to a panoramic view of the city’s beachfront skyline and the Pacific Ocean, a whole step darker than the sky. The group—clad in hard hats bearing the sleek logo of the new development—ooh and ahh, snap photos, saunter about.

This public relations Richtfest was to commemorate the “topping out” of The Current, at the time the city’s first high-rise apartment complex in over a decade. The $70 million tower was a local marker that the Great Recession had finally been shaken off. In that sense, the rose-colored outlook and swelling civic pride conveyed by city officials and the local press is somewhat understandable. For just a few years before, on that very same plot of land right across the street from the beach, was a parking lot and a vacant, rundown two-story building.

Consequently, the resulting coverage from the day’s rooftop sneak peak was peppered with words like “celebrate,” “thrilling,” and “breathtaking.”

The photo-op continued later that afternoon on the building’s top floor where Mayor Garcia proclaimed: “Anytime you change the skyline of a community you’re making a big, long-lasting impact.” That soundbite would prove to be prescient, and, depending on your income level, it would come to mean two very different things.

For the city’s power brokers, business owners, and rentier class it was a reason to celebrate. Long Beach—a city that despite its many natural endowments had historically struggled to get even an eye-bat from the financiers in New York and LA—had finally put something up on the board. So many false starts and failed developments were quickly retreating in the rear-view mirror.

And the victory had come after a string of economic gut-punches: the dismantling of redevelopment agencies and an economic downturn that nearly put the kibosh on this project, dubbed the Shoreline Gateway, located on one of the city’s most storied and prominent intersections. But in the end, capital and the local officialdom muscled the project ahead, for there were tax dollars and rent to reap.

A “new Long Beach” was on the horizon and this building, the first of two luxury apartment towers to be built at the location, would be the harbinger of a manifest destiny mapped out three years prior.

On Jan. 10, 2012—ten years ago this week—the Long Beach City Council held a momentous vote on a major overhaul of the Downtown Plan, the development blueprint that would guide the direction of the downtown’s growth and land use for the next 25 years.

Since its enactment, the plan has helped lift the downtown skyline by allowing developers to build taller with fewer parking requirements and less red tape. But the decision to push the pedal on unfettered market-rate development without adequate renter protections in place squeezed out an innumerable amount of working-class people from the city core and its peripheries.

This outcome had been foreseen when the Downtown Plan went before the council 10 years ago. Every analysis had predicted that it would lead to a mass dislodgement and exodus of renters, who occupied 81% of the housing downtown. And it was renters of color and the poor who would be especially hit hard.

David Paul Rosen & Associates, a highly respected economic development and public policy consulting firm, found that the plan would put nearly 24,000 existing low-income residents living downtown at high risk for displacement.

The Pew Charitable Trusts conducted a health impact assessment of the plan that found “the current and future needs for affordable housing in Downtown Long Beach can be expected to increase along with the impacts resulting from a lack of affordable housing, such as overcrowding, overpayment for housing, displacement, and homelessness.”

The city’s own draft Environmental Impact Report spelled out with clairvoyant precision the economic cleansing that would unfold:

“Implementation of the proposed Downtown Plan would … result in the displacement of existing housing and people, primarily housed in medium density multi-family dwelling units. New development would occur at higher densities and with more modern housing, frequently as part of a mixed-use development. While many residents would relocate into different dwelling units either within or outside the Plan area, they would be displaced from their existing dwelling units and may be unable to obtain similar housing with respect to quality, price, and/or location.”

Consequently, the council heard and received hundreds of pleas from tenants and community groups imploring city officials to pass a development plan that was as justice-oriented as it was market-oriented. Specifically, they wanted the Downtown Plan to be accompanied with policy to prevent renter exploitation and ensure the construction of affordable housing.

However, Bob Foster, the mayor at the time, threw his full-throated support behind the plan without concessions to renters. Meanwhile, Foster’s protégé, Garcia, who at the time was the District One councilmember, reportedly “spearheaded moving the Plan forward as-is.” After all, Garcia’s fingerprints were all over the planning document. As a member of the Downtown Visioning Task Force prior to being elected to the council, he had been one of its main architects.

“The city’s plan for downtown has totally failed,” Garcia told a reporter way back in 2008 just before he announced his council run. “We all agree with that. There is no argument on the other side. Look at all the empty storefronts.”

Having assumed a seat behind the dais and on the verge of imposing his new urbanist vision upon the downtown, Garcia still seemed much more interested in emphasizing buildings rather than people.

“While we’re discussing community benefits and issues that are controversial to the community, let’s not forget what a great plan we have that addresses all these other things,” Garcia said after hearing hours of public comments predominantly opposed to the plan. “For me the Downtown Plan isn’t just about this debate, but more importantly it’s about ensuring we are promoting these important issues like historic preservation, bold architecture, creating density in the right locations, design standards.”

Suja Lowenthal, then the vice mayor, called concerns over displacement “fear-mongering” and said, “Perhaps one person displaced is one too many but that’s a philosophical discussion we can have … but to suggest that this plan somehow invites that, I think, is specious at best and I’m troubled by that.”

Then-Councilmember Dee Andrews also chimed in: “I feel like we talk about low-income housing and everything else. If you have a job, you can move anywhere you wanna move.”

What it boiled down to for Garcia, Lowenthal, and the other proponents of the Downtown Plan, was that any sort of renter protection or affordable housing provision would overburden landlords and inhibit development.

Despite the sense of inevitability attached to the Downtown Plan, some councilmembers spoke out against throwing the most vulnerable populations into the furnace to power the engine of economic growth.

“What I want you to know is that low income is not just support workforce for hotels … It’s also seniors and, as we’ve heard, disabled adults who have found a way to have an independent life,” said then-Councilmember Rae Gabelich. “I think we speak too easily of just discarding people.”

Ultimately, the council voted to certify the Downtown Plan while denying an appeal from detractors. Gabelich and her colleague Steven Neal were the only nays. The council also rejected a motion from then-Councilmember Gerrie Schipske to study an inclusionary zoning ordinance, something many other cities had already put in place, but, as her sparring partner behind the dais Gary DeLong put it, “The last I read we have a tight budget here in the City of Long Beach.”

Fast-forward a decade to 2022. Lowenthal is a city manager in Hermosa Beach. Her former father-in-law, outgoing Rep. Alan Lowenthal (D-Long Beach) is endorsing a successor in Garcia, who is nearing the end of his second term as Long Beach mayor. Meanwhile, Schipske is vying to replace Garcia, as is Vice Mayor Rex Richardson, who was Neal’s chief of staff in 2012.

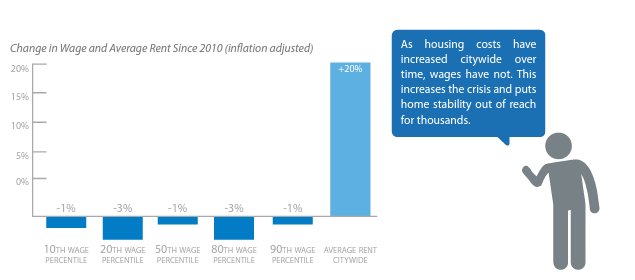

As for the downtown? It’s been filled out with expensive and identical-looking “one-plus-five” residential developments. Between 2010 and 2020, the 90802 zip code, which encompasses much of the city’s urban core, saw rents shoot up by 32%, the highest increase of any Long Beach zip code, according to the city’s latest proposed Housing Element. The document also states that wages in Long Beach have actually decreased during that same 10-year span, making housing less attainable than ever. Last year, the average rent in 90802 reached $2,001. According to the most recent Downtown Long Beach Alliance Market Survey, 1,673 new residential units have been built in 13 downtown developments since 2012, none of which are affordable housing projects.

All of this had been foreseen.

During a panel discussion at a Bisnow mixer held back in 2017 at the One World Trade Center—which was attended by a who’s who of local real estate, government, and business—Robert Stepp, president of the multi-family real estate broker Stepp Commercial, praised the city for cleaning up its “pop-culture” reputation and rebranding itself into something to the liking of investors. The panel speakers were all developers and real estate bigwigs, including an executive from AndersonPacific, which built The Current. During their discussion, the panelists were frothing with excitement over the prospect of rising rents, while cracking jokes about housing justice demonstrators outside the building.

“I was looking at something the other day and it said Long Beach rents have risen 13.3% in the last two years which is pretty amazing. And we have surpassed Atlanta and Portland in terms of a strong rental market. That’s been pretty amazing,” said Stepp.

Compounding the rising rents and decreasing wages, the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the growing crises of overcrowding and homelessness across the city, but especially in the downtown and its adjacent neighborhoods.

Then there’s the litany of negative effects on public health that come from reshuffling whole buildings and disrupting long-standing communities, which will never be fully quantified.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, low-income populations experiencing gentrification “typically have shorter life expectancy, higher cancer rates, more birth defects, greater infant mortality, and higher incidence of asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Mindy Fullilove, a psychiatrist and professor of Urban Policy and Health at The New School, describes this effect as “root shock.” She defines the term as the “traumatic stress response to losing all or part of one’s emotional ecosystem.”

It wasn’t until 2019—when the state was poised to cap rent increases and enact eviction protections, and seven years after the Downtown Plan—that Long Beach finally sprung into action and passed a tenant relocation assistance ordinance. And while inclusionary zoning was shot down the night the Downtown Plan was certified, it was eventually passed in 2020.

Between 2016 and 2019, I interviewed dozens of tenants who were facing displacement due to evictions or rent increases, without much recourse. These stories, often obscured by boosterism found in much of the local press, are as much a part of the legacy of the Downtown Plan—and the politicians who championed it—as any gleaming building that has since been erected.

These tenants told of the tremendous moving costs that drained their bank accounts. They worried out loud about moving their children to another school. They cried about leaving behind beloved communities—networks of trust built over decades of shared experiences. They described the disorientation of navigating a dog-eat-dog rental market full of predatory practices. They acknowledged the mental and physical toll brought on by the gnawing possibility of homelessness. And finally, time and time again, they expressed their stubborn love for Long Beach, the city that was kicking them to the curb.

Twelve of these stories are highlighted in the map below, which shows the location where each tenant was displaced, along with the date of the interview and a brief account of their displacement. Because the city doesn’t track evictions, these accounts are only a tiny sampling of countless similar experiences forever lost beneath the city’s new layer of lacquer.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores