Five Takeaways from the Latest Long Beach Housing Element

28 minute readGoing by the numbers in Long Beach’s recently adopted housing plan, “the rent is too damn high” sounds more like the PG version of what renters are actually screaming each time the first of the month comes around.

While Long Beach is not unique in feeling the crunch of the statewide housing crisis, the city’s eight-year housing plan reveals that there are areas where the city is faring worse than the rest of the region. In particular, Long Beach has major overcrowding problems in communities of color and a lot of old housing.

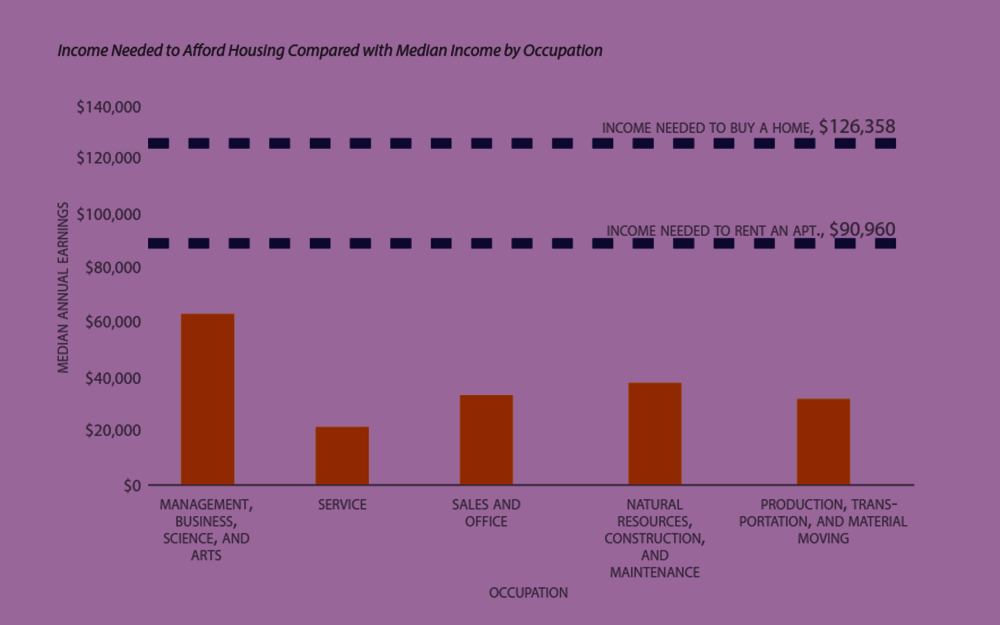

On top of that, 43% of all households are overpaying for rent. According to the housing plan, an income of $90,000 a year is needed to afford rent at an apartment in Long Beach without having housing expenses cut into money needed for other necessities. To afford mortgage payments on a home, a person would need to make about $126,000 a year.

Last month, the City Council adopted the newest version of the plan, known as the Long Beach Housing Element, before it was to be sent off to the state for final certification. However, because the city did not turn in the Housing Element to the state on time, it is one of 207 jurisdictions that will have to speed up its ongoing efforts to update its zoning code as a penalty.

California law requires all of its cities and counties to draw up a Housing Element every eight years. The document is part of the city’s General Plan and will guide future decisions around housing, including the location of new developments. But more than that, the plan looks at how the city will meet its housing needs and how future development aligns with the city’s goals around the environment, walkability, job creation, and more.

Just as important, the Housing Element provides deep analyses on the city’s current housing situation. It’s a dense document, clocking in at over 700 pages when you include its various appendices—which is where some of the most sobering information is found.

Also important to note is that this Housing Element cycle is unique for a few reasons. One being that it’s the first time cities were required to include a fair housing assessment, which looks at how exclusionary housing practices of the past and present have segregated Long Beach and created barriers to accessing housing for people of color. The city is also responsible for identifying fair housing goals and actions to overcome these barriers.

Another major difference this time around is that the state has shown much more willingness to clamp down on local governments that don’t meet their housing benchmarks. While California is still tinkering with the penalties it could impose on non-compliant cities, they could range from lawsuits to financial sanctions to suspending local control over building permits and zoning.

Below are five key takeaways from the Housing Element critical to understanding the local housing crisis and the future of housing in Long Beach.

#1 HOUSING PRODUCTION HAS REACHED A HISTORIC LOW

Like virtually every major city in California, Long Beach is short on housing—way short. There’s no easy explanation as to what’s caused this housing shortage—which has reached a “crisis level,” according to the Housing Element. Understanding it requires looking back over decades of policy decisions, economic phenomena, tax law, and obstructionism.

But in the spirit of keeping it short and sweet, some of the most commonly cited reasons are anti-growth activism, restrictive zoning, Proposition 13, the emergence of contract cities like Lakewood, the staunch opposition to pro-housing laws by powerful trade unions, the gobbling up of residential property by private equity firms, and racist land use practices of the past like redlining.

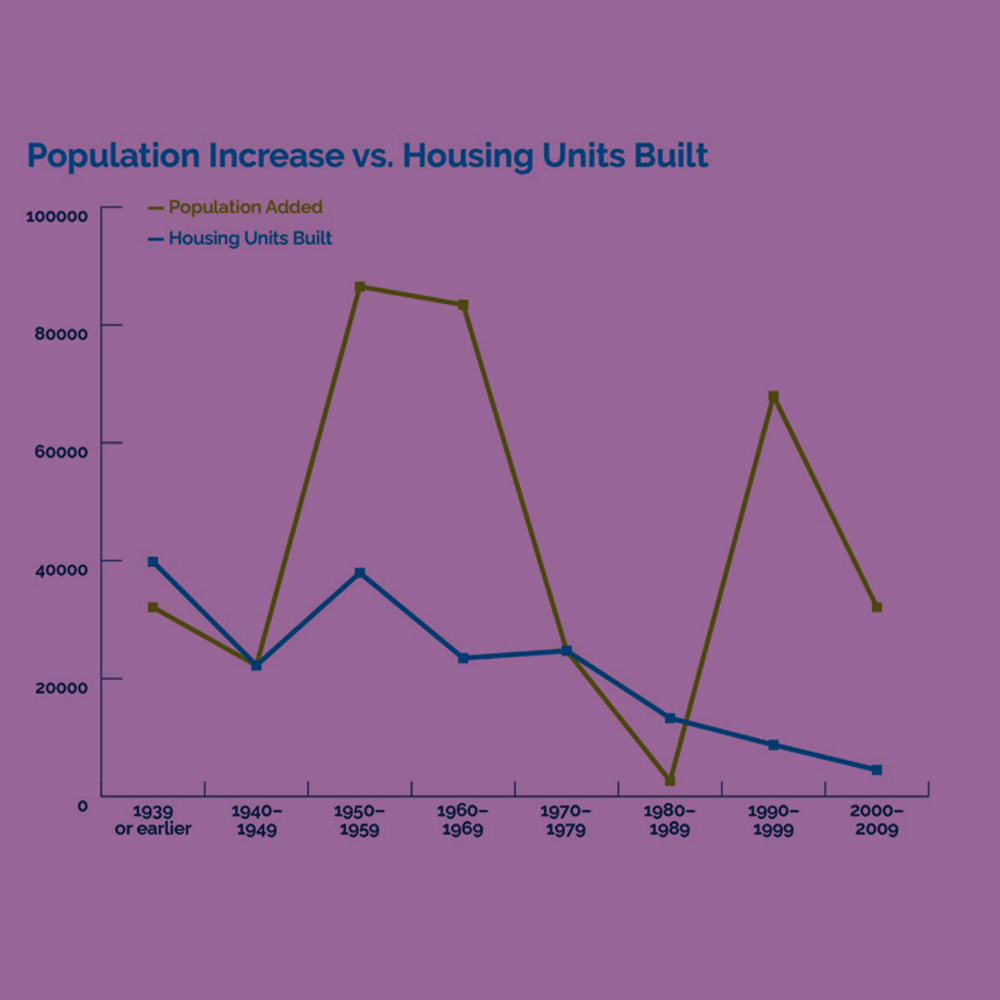

According to the Housing Element, Long Beach has seen a diminishing amount of housing production and an increase in population over the last 50 years.

Let’s first take a look at the housing numbers. Since 2010, only 1,622 residential units have been built. To put that into perspective, about three times that amount—4,494 new homes—were built in the prior decade. A graph included in the Housing Element displaying housing production over time shows this worsening bottleneck effect.

Meanwhile, population growth has far outpaced housing production. In the past 30 years, the city’s population grew 2.5 times the pace of its housing stock, according to the Housing Element.

Looking ahead, the city estimates that its population will swell by 15% through 2035, an even faster growth rate than has been seen in the past two decades. To catch up on the current housing deficit and accommodate this anticipated population boom, the state has tasked Long Beach with creating 26,502 new housing units between 2021 and 2029. This is known as the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) and this cycle’s target is about four times larger than the goal set in the previous eight-year period. Out of the 26,502 new housing units assigned to Long Beach, 11,000 must be set aside for lower income households.

Notably, much of this need won’t be filled by new construction, but instead by preventing housing that is already affordable—due to various voucher programs—from becoming market rate. The city is projecting that these conservation efforts will account for 10,424 residential units.

It’s projected that only about 9,900 new units total will be built from the ground up through 2029. Of those, the city estimates that 1,272 will be accessory dwelling units (ADUs), a source of housing that the city is banking on to be “a significant portion of the lower income housing” that’s needed. An ADU—sometimes referred to as a granny flat—is a small secondary residential unit on the same lot as a single-family home. The state is allowing cities to count ADUs toward fulfilling their RHNA requirements “based on the actual or anticipated affordability.”

While ADUs are being hyped as a major tool in alleviating the housing crisis, others are not as optimistic. Some have said cities are prioritizing ADUs over larger developments or upzoning because they aren’t as politically controversial. Others have pointed out that the affordability levels of ADUs are far from certain.

Even after using this patchwork of sources to tabulate future housing creation, the city estimates that due to funding constraints, insufficient city staffing capacity, and development trends, Long Beach will ultimately fall short of its RHNA goals by about 4,000 units. Still, achieving even that would be a monumental accomplishment considering the city only developed 59% of the 7,048 units it was supposed to build between 2013 and 2021.

#2 RESIDENTS ARE SADDLED WITH EXPLODING HOUSING PRICES WHILE WAGES HAVE STAGNATED

According to the Housing Element, the current housing shortage has been one of the primary drivers of skyrocketing housing prices. (Duh.)

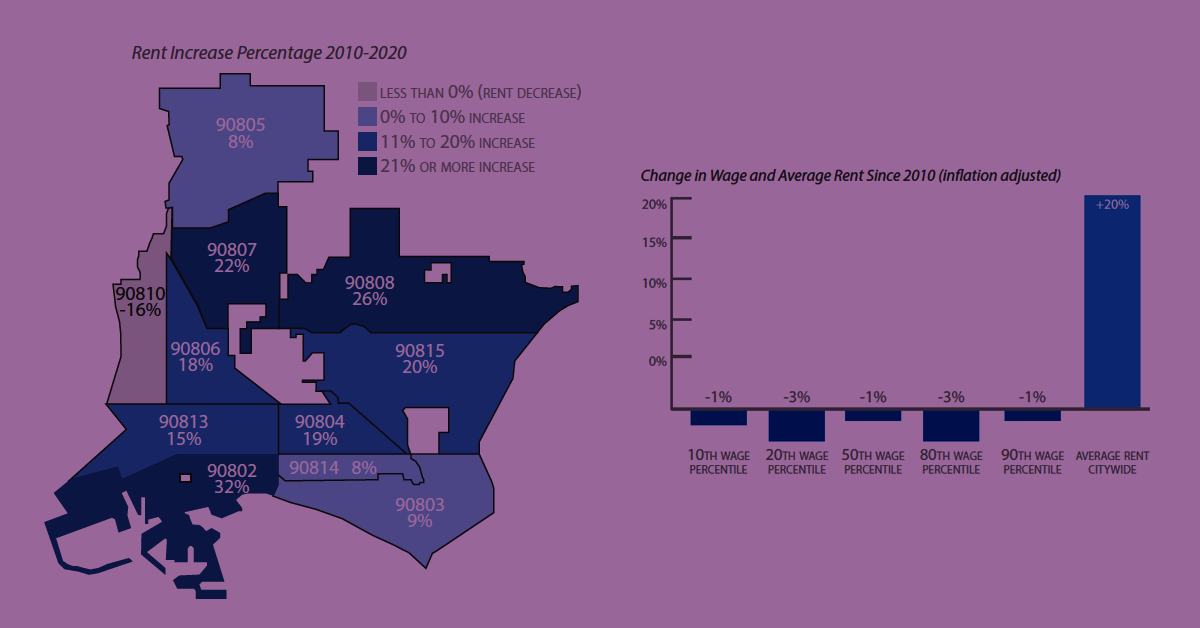

The median sales price of a home in Long Beach is $640,284 and the median rent is $1,895 per month, the Housing Element reports. Citywide, the median rent has gone up by 28% since 2010, which tracks just under the 31% increase in rents seen across LA County during that same period.

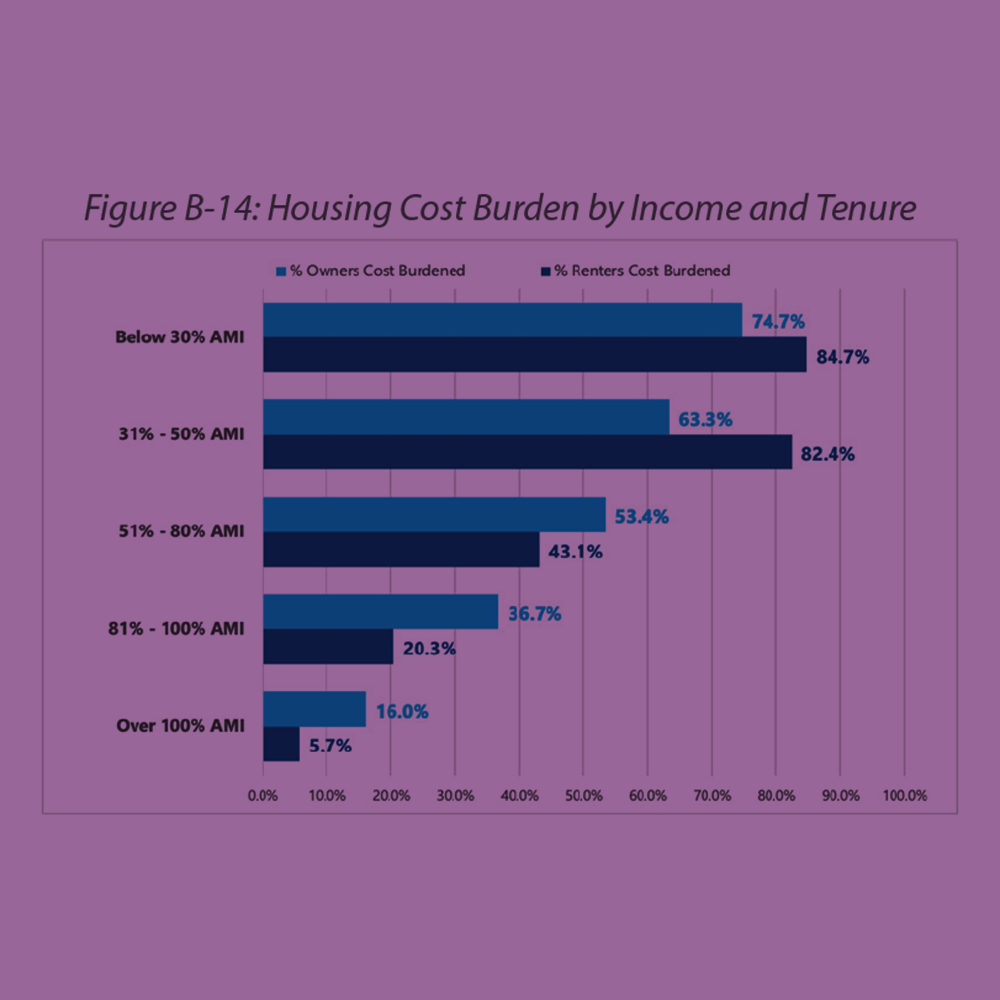

Nearly half of all residents in the city are housing cost-burdened, meaning more than 30% of their income is going toward rent or mortgage payments. This cost burden is more prevalent and hits harder as you move down the income stratas, where every dollar put toward housing past that 30% threshold begins to eat away not only at disposable income but at the ability to afford other basic necessities such as food, medical care, and transportation.

Eighty percent of very low-income renters are cost-burdened, compared to just 5% of renter households earning above-moderate income. One analysis from SmartAsset found that Long Beach was the fourth most housing cost-burdened city in the nation.

Disaggregating this data by race, the Housing Element found that over half of all Black and Latino renters are housing cost-burdened. And geographically, this economic pain is not distributed equally across the city. Rates of housing burdened residents are highest in North, West, and Downtown Long Beach. Over the last decade, the proportion of residents who are housing cost-burdened citywide has more or less remained the same, according to the Housing Element. Though, North Long Beach has seen an increase in the number of renters overpaying for housing.

“There are no areas of the City where overpayment has significantly decreased,” states the Housing Element.

And while housing prices have shot up, wages have actually decreased since 2010 when accounting for inflation.

Another worrying trend the Housing Element points to is the parallel rise of both high-wage and low-wage jobs, indicating that the local economy is becoming bifurcated between the well-off and the poor, increasing inequality and the need for subsidized housing. Since 2000, job growth has been most pronounced in the service industry (with a median annual income of $31,615) and in management and business occupations (with a median annual income of $63,886), according to the document.

One incredible graph in the Housing element shows that housing in Long Beach is essentially unaffordable to median earners in all major sectors. And with 57% of households earning less than $75,000 annually, at least 95,000 Long Beach households cannot afford a market-rate apartment at the median rent.

“For residents earning incomes near or below the median income levels indicated, both rental and ownership [of] housing is unaffordable without pooling multiple incomes, which often results in overcrowding and unhealthy housing conditions,” states the Housing Element. “Extremely low income households, in particular, have very limited housing options in the open market.”

#3 OVERCROWDING DRIVES DETERIORATION OF OLD HOUSING STOCK

About 20,000 of the city’s renters live in overcrowded conditions. Of those, 7% live in severely overcrowded conditions.

The state defines overcrowding as a household with more than one person per room (excluding bathrooms and kitchen). Severe overcrowding is defined as a household with more than 1.5 persons per room.

We wrote about overcrowding last year, and noted that some neighborhoods in Long Beach are among the most overcrowded in the nation.

These high levels of overcrowding are often driven by exorbitant housing costs, forcing some households to double up or even triple up in the available bedrooms or even in living rooms.

The Housing Element explains that this type of living situation is especially detrimental to kids: “Overcrowded situations can disproportionately impact children, leading to the perpetuation of intergenerational social inequities. The lack of comfortable space can lead to difficulty learning and poorer quality sleep. Children in overcrowded housing are also more likely to catch an illness.”

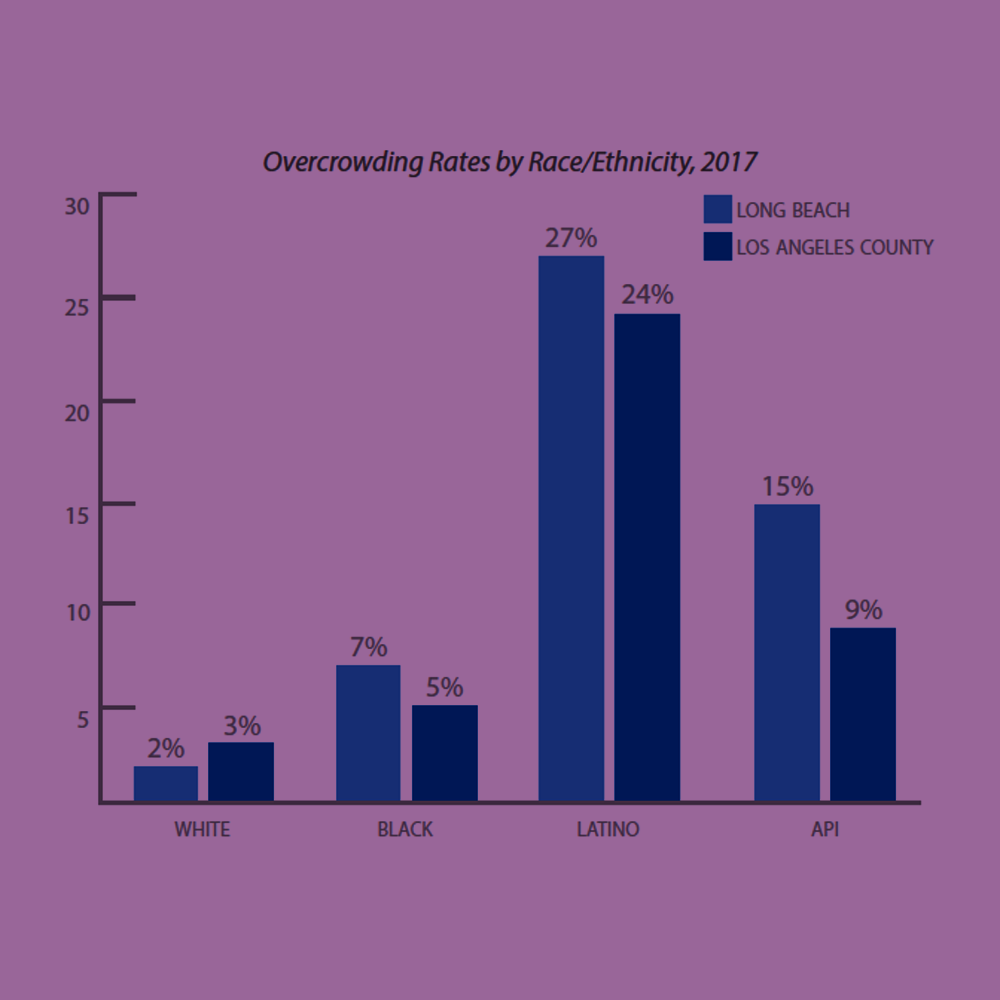

That last point has been brought into focus by the COVID-19 pandemic, showing just how dangerous overcrowding can be when dealing with an infectious disease. Going by local data, there is a correlation between neighborhoods that saw higher COVID-19 infections and those that experience the highest rates of overcrowding. Areas with the highest rates of overcrowding are located in Central Long Beach, along the Anaheim Street corridor. Wrigley and North Long Beach also had higher levels of overcrowding. Higher rates of overcrowding correspond with higher percentages of non-white population, according to the Housing Element.

Breaking it down by race, the highest rates of overcrowding are found in Latino households (24%), and American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander households (25%). Additionally, about 12% of Asian households in the city live in overcrowded conditions. And to the surprise of no one who’s made it this far, overcrowding also disproportionately impacts low-income households, the Housing Element reports.

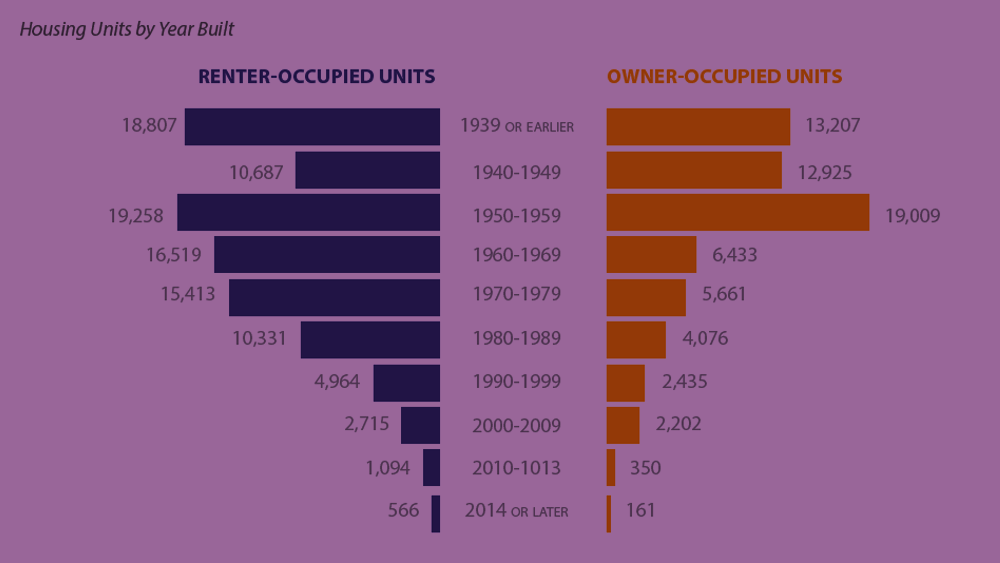

Another effect of overcrowding is that it can lead to the accelerated deterioration of housing. This is concerning because Long Beach has an especially high proportion of older housing: 71% of housing in Long Beach is over 50 years old, compared to 61% across LA County.

“Given the high rates of overcrowding in Long Beach, which are concentrated in areas of the City with the oldest housing stock, safety and health issues related to the advanced age of housing stock are even more urgent,” the Housing Element warns.

During fiscal year 2020, the city opened 4,382 code enforcement cases. Our own analysis of this same data found that among those cases, 323 code enforcement violations were issued against property owners during that period for unsanitary conditions, mold, and infestations of cockroaches, bed bugs, and rodents.

Studies have linked cockroach infestations and mold to respiratory issues, such as allergies and asthma. Rodents can carry dozens of diseases and infestations can cause negative psychological effects.

#4 THE LAND USE ELEMENT CRYSTALLIZED SEGREGATION

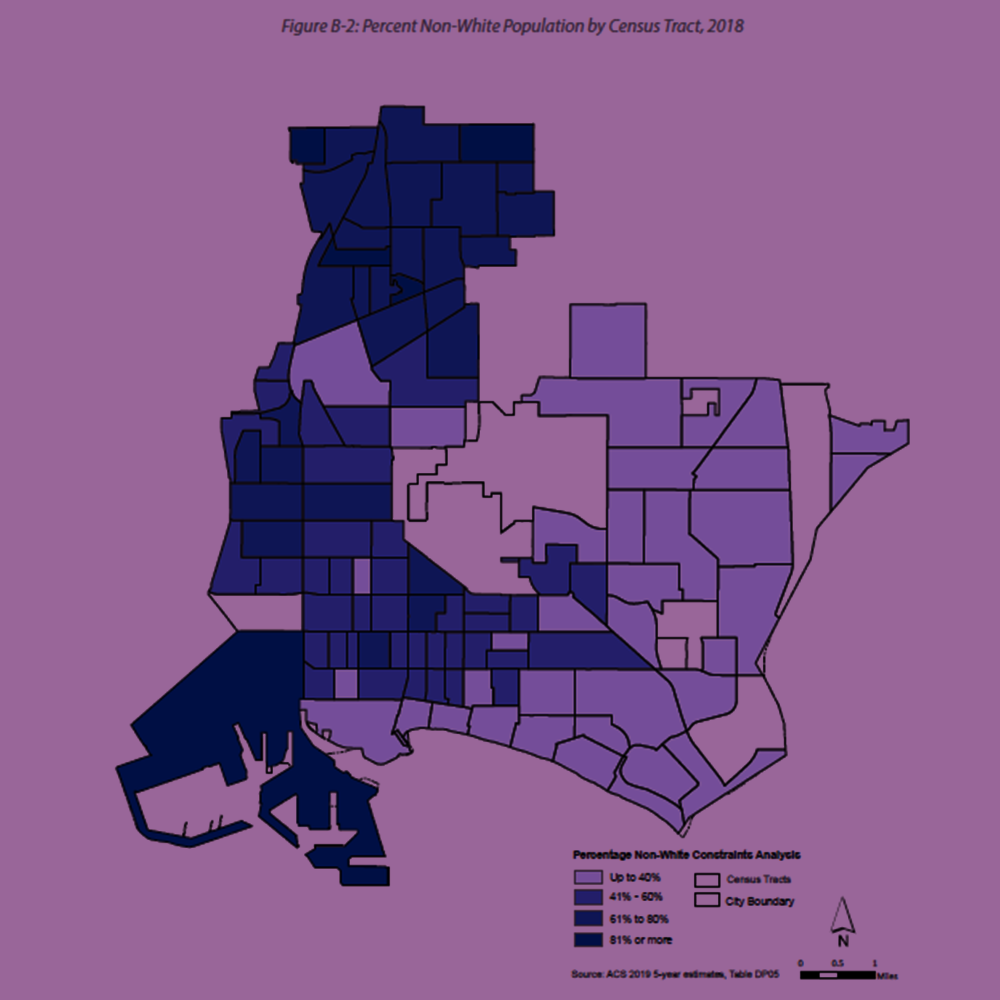

Long Beach is a highly segregated city, even in the year 2022. Below is a map from the Housing Element showing the spatial distribution of white and non-white residents across the city.

Using what’s called a dissimilarity index to measure housing segregation, the city found not only that segregation between white and non-white residents is high but that it has been increasing since 1990. According to the Housing Element, this segregation is due to “longstanding and ongoing political, social, and other factors.”

Breaking down exactly why this map looks the way it does could be its own article but, essentially, you can chalk up the east-west segregation to two main factors: One, the racist housing policies of the last century—things like redlining and blockbusting—that forced people of color into the most undesirable areas of town. And two, the present-day zoning scheme that largely keeps affordable, multi-family residential buildings out of the city’s bedroom communities in the east, perpetuating the overtly racist land use policies of the past.

According to the Housing Element, the neighborhoods with less pollution and better schools are “inaccessible to low-income communities of color which continue to suffer from the legacy and continued impacts of exclusionary and discriminatory policies and systems that are reinforced by market forces.”

Crucial to this story is remembering that city leaders had a chance to take a big swing at the housing segregation problem back in 2019 when they made the first updates to the Land Use Element (LUE) in nearly 30 years. The LUE is a map the city is mandated to draw up that suggests changes to local zoning and designates where certain types of buildings can be built.

Over the course of several public outreach sessions, pressure mounted from mostly white single-family homeowners demanding lower density in eastside neighborhoods. In response, the city whittled down the density in the LUE—most notoriously in District Five. By the time the LUE was passed by the council, the density in the eastside had been significantly scaled down compared to the original drafts.

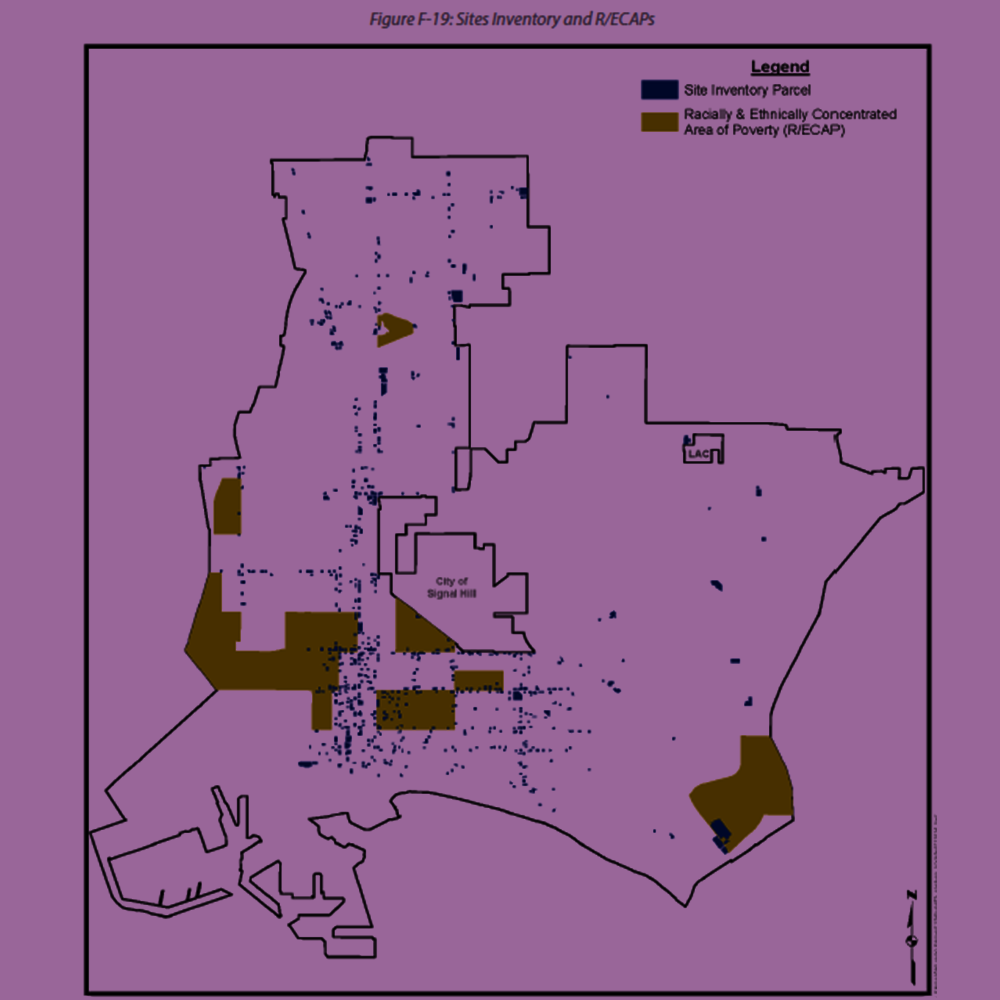

In doing this, the city greatly narrowed its options when it came time to identify sites that are “eligible and likely to be developed” into housing over the next eight years to accommodate future growth, a statutory requirement of the Housing Element. A close look at this inventory shows that city planners had to cram much of the city’s potential housing sites into lower income areas already saddled with pollution, poverty, and displacement. This means there could be an onslaught of (more) displacement in the years to come—especially if renter protections aren’t proactively strengthened.

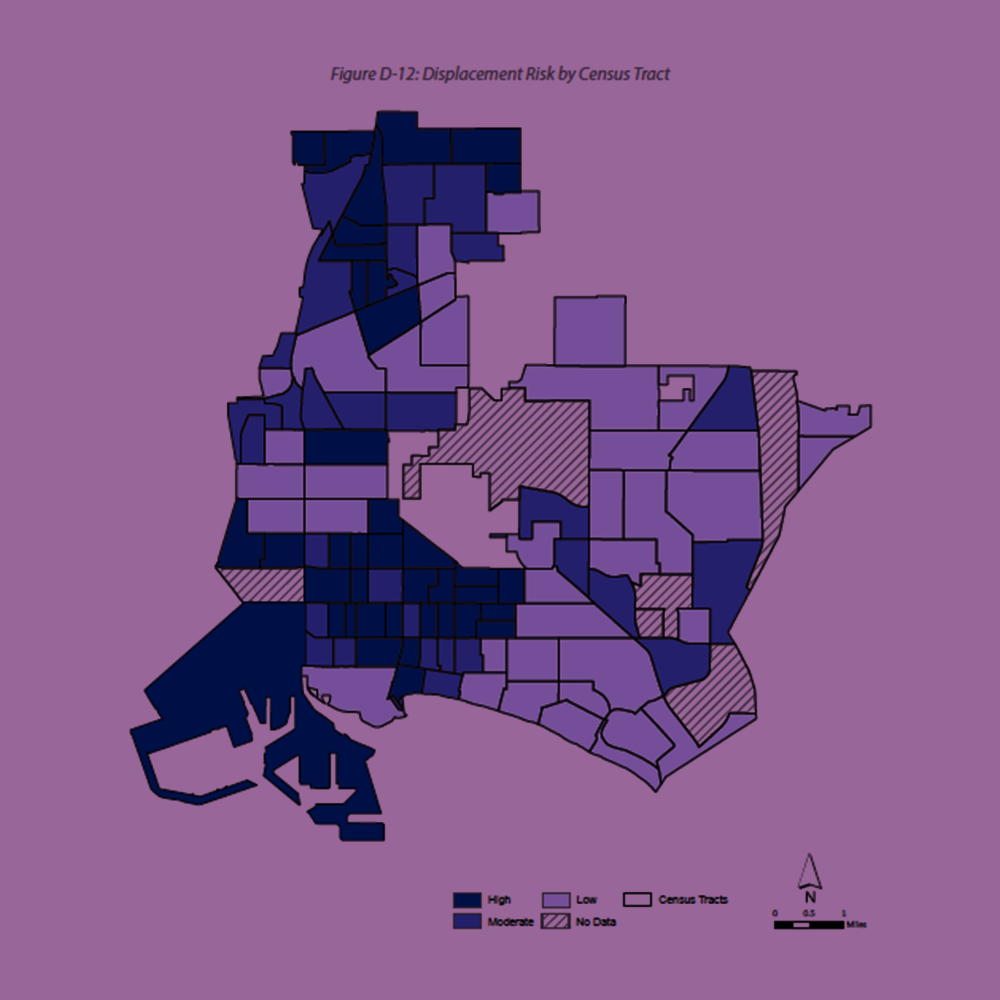

The Housing Element includes a map showing the displacement risk of neighborhoods across the city. Downtown, Central, and North Long Beach, as well as Cambodia Town, all have a high to moderate displacement risk. Comparing that map to the city’s site inventory map shows that many of the parcels the city hopes will be turned into housing lie in those areas.

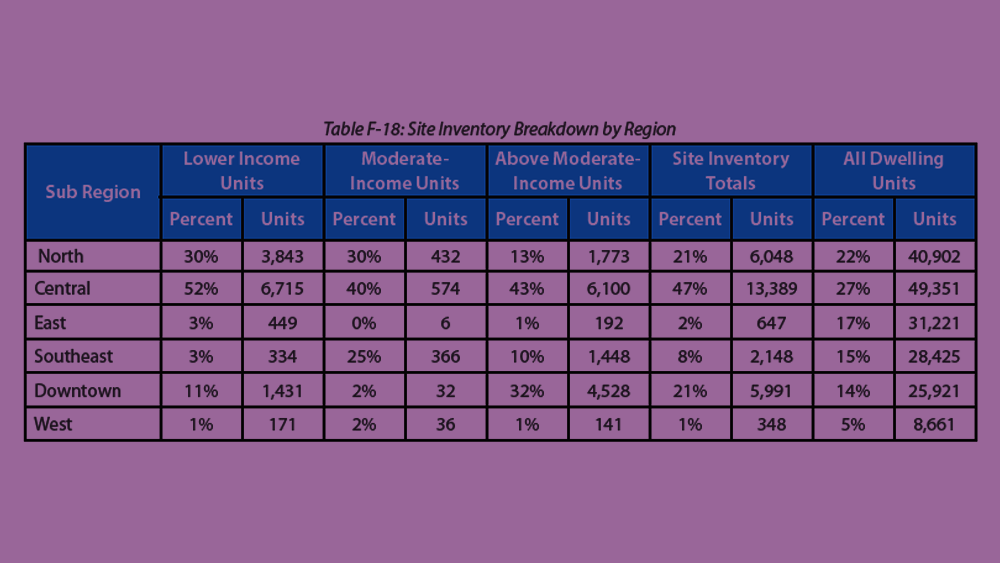

According to the Housing Element, Central Long Beach contains a whopping 47% of all the potential housing sites identified while the east and southeast parts of the city contain a combined 6%. Downtown and North Long Beach each contain 21%. Moreover, 82% of sites for future low-income units are in North and Central Long Beach, areas that already have a high amount of concentrated poverty and lower access to resources. Apart from the constraints put in place by the LEU, city planners have said these areas contain major transit stops.

The Housing Element shows that about 46% of all potential housing sites are in neighborhoods with high poverty/low resources, accounting for 13,086 housing units. Meanwhile, areas with low poverty/high resources are only assigned 14% of the housing share, or 4,041 housing units.

Councilmember Suely Saro, whose Sixth District includes much of Central, touched on this disparity during a hearing for the Housing Element in November: “I know that the LUE has been an element of challenge, but I want to know how can we continue to work at this so that there are housing sites identified that are evenly spaced out because there’s [only] so much density we can put over the next eight, 10 years in the region that already has high density.”

She went on to say: “That’s why I’m concerned that we’re having less identified sites in areas that are less dense … I’ll speak to my district, I feel that I’m carrying a lot of the burden of the housing production.”

In response, city staff pointed to a monitoring program baked into the Housing Element that will track the geographic distribution of residential units over time and could trigger additional fair housing strategies if disparities continue or get worse. One possibility mentioned by Planning Bureau Manager Patricia Diefenderfer is that the council could decide to make adjustments to the LUE if it is impeding housing production.

The conversation around neighborhood segregation came up recently in July when the City Council addressed the new Belmont Aquatic Center, drawing a notable contrast with the Housing Element. When the council was pressed about the new $85 million pool being located in one of the whitest most well-to-do parts of town their justification was that it would help to integrate Belmont Shore. The council cited the free shuttle service that will bring Black and brown residents to the facility.

“People were also talking about, ‘Why are you building [the pool] here in the Third District, in one of the most highest rent districts in the city? Why don’t you build it somewhere else where people can have more access?’ Well that’s segregation,” said District Seven Councilmember Roberto Uranga, who is also on the California Coastal Commision. “What’s the matter with integrating the Third District?”

District Three Councilmember Suzie Price also made similar remarks: “The whole idea of equity and integration is bringing people together in different communities.”

The contradiction here is what city leaders choose to call integration varies starkly depending on the community. When an affluent white neighborhood gets a public pool—largely to be paid for with oil extraction revenue, an industry that disproportionately harms the health of people of color—it’s called integration, even though Black, brown, and poor people bussed to the facility will inevitably return to their homes in Central and North Long Beach. But, as the Housing Element shows, when it comes to denser housing, high-income neighborhoods are largely spared. That burden is instead disproportionately hoisted onto the city’s most impoverished low-resource communities—all in the name of integration.

#5 CITY TO CONSIDER RENT STABILIZATION… BUT DON’T HOLD YOUR BREATH

The city’s housing challenges are obviously steep and it will need to build a lot of housing to get out of the hole. But as we saw with the Downtown Plan in 2012, building housing without strong safeguards for renters can have disastrous effects for lower income communities, where most of the new housing is projected to be built in the next eight years. So what does the Housing Element propose in terms of future renter protections?

The document’s most eye-catching commitment is the city’s willingness to explore rent stabilization. Rent stabilization regulates how much rents can be increased, usually capping it at a small, set, annual percentage. The state already caps rent increases at 10%, but the city could go even lower. Usually buildings with few units are exempt from rent stabilization and landlords are allowed to reset the rent when units become vacant. Rent stabilization is often confused with rent control, which in contrast freezes a unit’s rent price until a tenant moves out.

The city is proposing to study how rent stabilization has worked in nearby cities and publish a report sometime in 2023. That timeline has been criticized by tenant advocates.

“This is not good enough—a basic report should not take two years and will only delay any eventual adoption of the policy,” the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles wrote in a letter to the City Council. “Tenants are facing extraordinary displacement pressures due to the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy options to prevent this must be explored and put into place as quickly as possible.”

Another tenant protection the city says it will look into is establishing first right of refusal for income-qualified residents displaced by developments in the areas covered by the inclusionary zoning policy, which are currently Downtown and Midtown. However, the city doesn’t anticipate such a policy being enacted until at least 2025.

According to the Housing Element, administering many of the tenant protections the city is hoping to put in place in the future will require a dedicated staff. To that end, the document proposes allocating funds to create a Rental Housing Division by 2024 and getting the approval of the City Council by 2025.

But the Legal Aid Foundation also questioned this plan in their letter, noting that a Rental Housing Division would need to be in place before other rental protections can be applied.

“This is why the current timeline, with a Division being in place in 2025 at the earliest, is unacceptable,” the organization wrote.

Finally, the city is looking to lend a hand creating community land trusts, which allow an independent community-controlled group to buy housing and take it out of the market, thus preserving its affordability.

Moving forward, the Housing Element says the city will provide technical assistance to community groups and other private organizations looking to establish “Community Land Trusts or other model for facilitating community ownership of affordable housing, including identifying and pursuing eligible funding pools.”

The city already dedicated $1 million toward researching community land trust models in the last budget.

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores