‘Once It’s Gone, It’s Gone’: West Long Beach Still Awaits ‘Promised’ Park, Residents Protest New Developments

20 years ago, leaders sought to increase West Long Beach’s park space eightfold. It’s still nowhere close. On Nov. 15, the last substantial parcel of land in the nature-deprived and over-polluted area may get the greenlight for development instead.

20 minute readWest Long Beach has only one acre of park space (less than the size of a football field) for every 1000 residents, and the opportunities to create much needed green spaces are dwindling fast.

Long holding the designation as a “diesel death zone,” the nonstop onslaught of toxic emissions from the convergence of the freeways, multiple refineries, and an international port complex have caused the area to be ranked by the CalEnviroScreen in the highest percentile for pollution burden.

Back in 2002, Long Beach’s Open Space and Recreation Element, a document that is mandated by the state to be included in the city’s general plan, set the goal to increase the acreage of parkland in West Long Beach eightfold.

It has been 20 years since then and this still has not been achieved.

As these issues continue to compound, a crisis situation has been created that includes negative public health impacts such as high rates of asthma-related deaths. According to CalEnviroScreen, “The asthma rate is higher than 85% of the census tracts in California.”

As described in the “Existing Conditions” section of the current Long Beach Parks, Recreation, and Marine Strategic Plan that was approved in January, there is a big discrepancy in park space between the east and west parts of the city. “The goods movement has dominated land-use development across West Long Beach, with the needs of the port and industry prioritized over community needs,” states the plan.

For comparison, the east side of Long Beach, near the affluent and much more white El Dorado Park Estates neighborhood, has almost 17 acres per 1000 residents. Their life expectancy is also at least five years longer than folks on the westside.

When the city was discussing its Racial Equity and Reconciliation Initiative in 2020, Long Beach’s long history of redlining was acknowledged. Redlining and other racist housing policies played a big part in the demographics of the park-poor westside which is currently 76% people of color. The commitment to achieve equitable park space is now referenced in city documents as a goal.

WRIGLEY HEIGHTS RIVER PARK VISION

A grassroots group of neighbors and environmental justice advocates called the Riverpark Coalition is worried it is too late for West Long Beach.

Pushing to save what they see as the “last two opportunities” for substantial parkland in the area, the Coalition says they are just asking for what has long been “promised.”

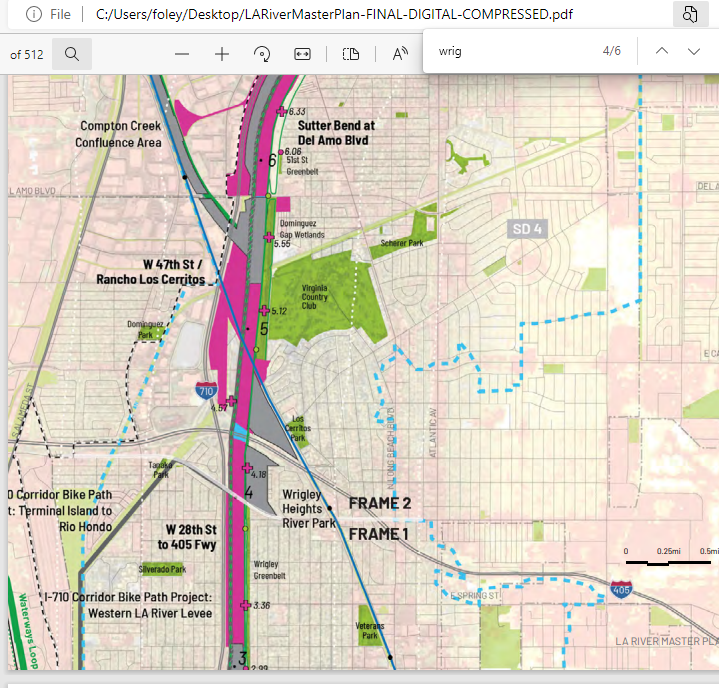

The two parcels of land in question are divided by the 405 Freeway, 3701 Pacific Pl. (to the north) and 712 Baker St. (to the south, in an area called Wrigley Heights), lay adjacent to the Los Angeles River and less than 700 feet away from the 405’s intersection with the 710 Freeway. Beginning in the 1920s, the land was owned by Oil Operations Inc. which used it as a waste pond for several decades.

Members of the Coalition, such as longtime residents Ann Cantrell, Carlos Ovalle, and David Walker, say a greenspace connected to the nearby LA River has been envisioned in the vicinity since the late 1990s.

They also point out that numerous city documents throughout the years have listed Wrigley Heights as a river park, including the Long Beach Department of Parks, Recreation, and Marine Strategic Plan (2003), the RiverLink Plan (2007), West Long Beach I-710 Community Livability Plan (2008), and West Long Beach Livability Implementation Plan (2015), as well as the LA River Master Plan (first drafted in 1996, last updated June 2020) which still has it listed as a “planned major project.”

Both parcels would need to be cleaned up from the years they spent soaking up oil industry toxins in order to become the “gem” of the Lower LA River that has been imagined. Rather than Long Beach having to pay for that work to be done, however, a self-storage unit and high-density residential development have been proposed, with the developers of each required to pay for remediation instead. Both projects are in various stages of progress.

The first proposal was for the property north of the 405 Freeway and was submitted by InSite Property Group (IPG).

In addition to 3701 Pacific Pl., which is a 14 acre plot, IPG’s project also encompasses three adjacent parcels at 3916-4021 Ambeco Rd. The latter properties are a total of 5.5 acres that formerly belonged to the McDonald Family Trust. IPG’s plans (after land remediation) include a three-story storage unit complex, 528 parking spaces for recreational vehicles, a carwash, and various buildings with office and warehouse space, as well as public access to the LA River.

Despite the protests of the Riverpark Coalition members, the project passed City Council on April 13, 2021.

After the City approved the proposal without requiring an Environmental Impact Report (EIR), the coalition joined water watchdog group LA Waterkeeper and lawyers from Chatten-Brown, Carstens & Minteer (environmental lawyers out of Hermosa Beach) to sue them for violating the state’s environmental review law.

Last month, Judge Mitchell L. Beckloff of the Los Angeles County Superior Court ruled in their favor. The court said that the city had violated the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) when they decided to waive the EIR in favor of a Negative Mitigation Declaration instead.

Current status: With this legal win, the project is halted at least until a proper EIR is done. Which means not indefinitely, stay tuned.

On Sept. 1, a project proposal for the 712 Baker St. property (Wrigley Heights South) was on the Planning Commission agenda. The 21-acre plot is sandwiched between Baker Street Mini Park and the Wrigley Dog Park. The developer would like to remediate the land and then add a 226-unit residential development that includes public access to the LA River, as well as promises to make some improvements to the existing parks while connecting them to a little under five acres of additional park space.

In exchange for providing the bare minimum of affordable housing (5%), the developer, Artesia Acquisitions Company LLC, is also now given a “menu” of state-mandated “entitlement” options. The company, which is based in Redondo Beach and Florida and just incorporated in 2021, is entitled to raise a 53-unit row of carriage townhomes from two to three stories because 12 of those units are promised to be affordable housing.

Riverpark Coalition members and many others signed up to speak against the Baker Street project proposal during the public comment portion of the planning commission meeting. As they had when the Pacific Place proposal was up for discussion, they reminded the current city staff of the long-held vision for the Wrigley Heights River Park and voiced concern that the opportunities to make it happen had run out. If not on either of those two parcels of land, where could a substantial park space go?

THE FEASIBILITY ‘SHAM’

City staff have repeatedly responded to the calls for the Wrigley Heights River Park by pointing to a study by City Manager Tom Modica from April 2021 that deemed park construction unfeasible due to the land being private property. A lack of funding and zoning issues were also cited as hindrances by the city.

In a press release regarding the feasibility study, which they refer to as a “sham,” the Riverpark Coalition disputes that the land was not able to be bought and alleges that the city never even put in a bid.

A city staff generated FAQ disputed that any property had been specifically designated for park space or that they had funds for making a purchase and cleaning up the land themselves: “The LA River vision plan does show the option of parks and open space in this general vicinity. No funds have been received or allocated for the acquisition of private property nor for the required toxics remediation.”

The city acknowledged in the same FAQ that in 2001 it was given $5.2 million in funding towards “acquisition or development of park space in this general area” but says “no agreements were reached with private property owners.” Long story short, Long Beach basically sat on the money for two years and then transferred it to the Rivers and Mountains Conservancy, a state agency. The stated intention was for the Conservancy to work with the Trust for Public Land to acquire park land. Eventually, according to the city, it was “clawed back by the State of California for budget balancing purposes.”

The Riverpark Coalition recently compiled a list of two dozen potential funding sources and submitted it to the city. On it were a range of applicable conservation measures, propositions, and other funding and land acquisition efforts out there (intended for park-poor areas, for revitalizing the LA River, for climate change mitigation, etc.) along with an assessment for each one regarding why Long Beach should be able to access it.

In regard to zoning being referred to as an impediment to the creation of the River Park, the Baker Street project involves changing the zoning as well. Why can the City change the zoning from a commercial space to a residential plan that allows 15 dwellings per acre (RP-15), but cannot change the zoning into open space for a park?

Noting that Mayor and soon-to-be Congressman Robert Garcia also received $10,000 from IPG for his campaign for Congress, Walker, a former Riverpark board member said he feels like, “The purchaser threw money into our politicians’ accounts to get them to sway the zoning… and encourage the sale.”

He and the rest of the group are upset watching their Wrigley Heights River Park dream being foreclosed on.

“We need this green space. Once it’s gone, it’s gone,” Walker says.

Tomisin Oluwole

Coquette

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Photo by Erin Foley.

RED FLAGS ABOUND

The Riverpark Coalition and the lawyers from Chatten-Brown, Carstens & Minteer were glad an EIR was actually required for the Baker Street project but submitted a 20-page objection detailing the ways they found it to be deficient and in violation of CEQA. One of the main complaints stated is that the document neglects to disclose “significant impacts on land use,” including its effect on using the vicinity for equestrian purposes, among others.

The lack of disclosure of cultural significance for the local Tongva people in regard to tribal cultural resources is also in dispute.

For an example of inconsistency, the document prepared by the Riverpark lawyers points out that the EIR says that no southern tarplants (considered a rare species that is designated for protection under state law) were found on the Baker Street property. The lawyers wrote, “The conclusions of the EIR’s biological resources section are curious, given that biological resources consultant LSA documented 830 individuals [plants] on the adjoining property.”

The project also requires a traffic signal at Wardlow Road. The lawyers wrote, “The EIR fails to explain how a traffic signal that was previously considered unsafe is now acceptable.”

Since the property is desperately in need of being cleaned up, the process for doing so needs to be included in the proposal and it should be approved by the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board (LARWQCB). Though a Remediated Action Plan (RAP) is included, the lawyers write it is not detailed enough, it is “too speculative” and has not been “fully defined,” nor has it been approved by the LARWQCB yet.

To sum up their assessment, the lawyers write, “The Project’s elimination of the last remaining large piece of open space in western Long Beach available for park purposes would unearth toxic soil, increase air contamination, traffic, and construction impacts in an already pollution burdened and nature-deprived community, and subject residents to a host of environmental harms.”

GARCIA ADVISED TO RECUSE HIMSELF FROM UPCOMING COUNCIL HEARING

Earlier in the afternoon on Sept. 1, a few hours prior to the Planning Commission meeting for the Baker Street project, Cantrell noticed a letter from Mayor Garcia to the commission’s chair Dr. Joni Ricks-Oddie included with the submitted public documents.

In the letter, Garcia encouraged Ricks-Oddie and the rest of the commission to cast votes in favor and recommend approval of the project. In addition to advancing climate change goals, he wrote, “This will move our city closer to accomplishing not only our own housing goals, but the goal set out by the State – upholding our city’s record as a national leader and model.”

Cantrell emailed the City Attorney’s office alerting them to what she saw as an impropriety, asking if the meeting should be postponed for legal reasons.

Two hours later, Cantrell received a response from the Assistant City Attorney Dawn McIntosh. In the email was the assurance that Garcia’s actions were not “illegal,” but that the mayor had been advised to now recuse himself when the project later came up before City Council.

The meeting then went on as planned.

During public comment, former 8th District Councilmember Rae Gabelich remarked that when it came to securing funding and bidding for the land, “chances are the efforts have never really been there.” Gabelich (who worked with Garcia back when he was the 1st District’s councilmember) says she has observed minimal effort to change the reality of park-poor West Long Beach.

Garcia’s claim that the dense residential project would help affordable housing and climate change goals was also challenged by each of the public speakers.

No one disputed that affordable housing is something Long Beach has dropped the ball on for years. Their issue was that 12 units is not going to make a big enough dent in the city’s goals to warrant the ensuing environmental and health impacts.

The Riverpark Coalition lawyers point out that, “the DEIR (Draft Program Environmental Impact Report) admits that the project site’s freeway-centric location, alone, would expose new residents to levels of pollution beyond the South Coast Air Quality Management District’s (SCAQMD) threshold of significance for excess cancer risk.”

Housing advocates have pointed out that the development is likely to cause the rates for rent to rise in the area as well.

Climate change concerns and further CEQA violations were alleged by several speakers.

Coalition members have pointed out that both projects are likely to exacerbate the problems that Long Beach’s 875-page Climate Action Plan (CAP) was intended to address when it was approved in August. On the flipside, each of the main goals of the CAP in regard to dealing with poor air quality, rising temperatures, sea level rise, and drought, are generally positively affected by the addition of parkland.

When it was Ann Cantrell’s turn to speak, she mentioned the harmful effect of adding such a dense housing project. If the city was going to go through with the developments instead of greenspace, Cantrell said, at the very least, “the projects should reflect the goals of the CAP.”

Tilly Hinton said she had been living in and researching the LA watershed for the past decade. She has been corresponding with the city since 2021, “enumerating” the many issues she has with the projects’ use of the land.

One of Hinton’s main worries was that, “such a significantly sized development—the roof acres, the sealed road, and so forth—would create potentially catastrophic urban heat island acceleration.”

Mentioning the city staff’s “enthusiastic advocacy” for the projects, she expressed “extreme dissatisfaction” with the decision for Long Beach to “abdicate its responsibility to provide equitable access of green space purely on the basis that the land is a private space.”

Citing the city’s “civic responsibility” and the need to protect the ecology of the land, Hinton also mentioned the “opportunity cost of not planting this crucial site with trees, plants, and shrubs.”

“It’s not a once in a generation opportunity, it is a once in many generations opportunity,” she said.

Some of the speakers asked if construction had already started as they saw a 15-foot pile of dirt dumped on top of the space. Amy Harbin, Project Planner for the city, explained that it was not construction but simply a “surcharge” being used in the ongoing state mandated process of soil remediation.

A public commenter named Michelle, who said she lives across the street from the proposed project site, related to the council that she had “smelled petroleum” when that dust was being kicked about.

Another neighbor named Kailen Williams reported the same smell during his turn. He also lamented never getting to enjoy the park he had seen plans for when he moved into the neighborhood seven years prior with his then one year old son.

After public comment finished, City staff responded to the smell complaint saying that they were watering the dirt to make sure that the toxic dirt didn’t fly about and that the onus was put on the SCAQMD or the LARWQCB to investigate in times of ill smells. The agencies don’t have anyone monitoring air quality, so the presence of a high volume of calls is the main alarm system.

“You have to call continually,” in order for the SCAQMD to take action if you smell something, city staff advised, “get your neighbors to call, too.”

Despite the many other concerns of the public commenters, only one member, Commissioner Mark Christoffels, expressed uncertainty about the vote. Saying he wasn’t “comfortable” voting on it, he also acknowledged that it was “going to City Council anyway.” It passed with his vote remaining the only dissenting one.

Next step for the Baker Street project: a City Council hearing on Tuesday. Members of the public are encouraged to participate in the discussion.

If the project EIR and zoning change is approved by the City Council, Cantrell said they just “may end up in court again.”

erin@forthe.org

erin@forthe.org