PERSPECTIVE: Heineken, High Rent, and the Long Beach Housing Crisis

11 minute readWhat follows is a personal perspective of the author, and not an official position of FORTHE Media.

Introduction

During last month’s Pride parade in our city, Long Beach’s First District Councilmember—and soon-to-be State Senator, Lena Gonzalez—chose to enjoy the route atop a giant, green Heineken bus, emblemed with the multinational, multibillion-dollar corporation’s latest condescending condolence to America’s working class: “High rent means living with your six best friends.”

Upon seeing the featured photo, my first thought was, “How can we stop ads like this from appearing in our city?” My second thought was, “Wouldn’t it be swell to have leaders in our city who were conscious of the toxicity and stupidity of capitalist advertising, its relation to the corporate domination of American culture, and their shared role in perpetuating poverty, and who went out of their way to fight shitty ads instead of parading on them?”

For those reasons alone, it’s worth bringing this back into the public’s mind, one month later; but there is also now the added issue of who will replace Gonzalez on the City Council. On Tuesday, voters in California State Senate District 33 elected Lena Gonzalez to fill the vacant Senate seat. Gonzalez defeated Cudahy Councilmember Jack Guerrero by a substantial 38 point margin.

Perhaps knowing this result was inevitable from the start, Gonzalez did not try to run a very grassroots campaign. She outraised and outspent Guerrero over 20-to-1, relying largely on donations over $1,000. In fairness, when your opponent openly calls to overturn Roe v Wade, you don’t have to do much at the grassroots level to distinguish yourself to California voters. Gonzalez was not very open to public questioning, or very accessible to the local media—apparently because she didn’t need to be available to win.

A great illustration of this point can be found in last month’s Heineken campaign gaffe. Despite multiple attempts by supporters of her campaign, and members of her Council District, to reach out to her via social media with questions about her gaffe, she has still not responded. While the pictured ad is tasteless for a few reasons, Gonzalez appearing above it is particularly problematic considering Long Beach’s ongoing rental crisis, and the fact that Gonzalez’s district is feeling the worst of it.

Long Beach’s rent crisis

The same week Gonzalez got on a Heineken bus bearing the slogan, “High rent means living with your six best friends,” a study was released concerning households in America that are “severely housing cost-burdened”—defined as paying more than 50 percent of their income on housing. It found that Long Beach has the 7th highest rate of such households in the nation.

The same report released last year did not include Long Beach in the top 10. That’s because high rents have been a steadily-growing problem here for years, and are peaking now to levels obscene even on a national scale. A March report from the city found that, in the 90802 zip code (largely Gonzalez’s council area), rents have increased over the past decade by almost 40 percent (page 44). Yet another report released a few weeks prior observed the following:

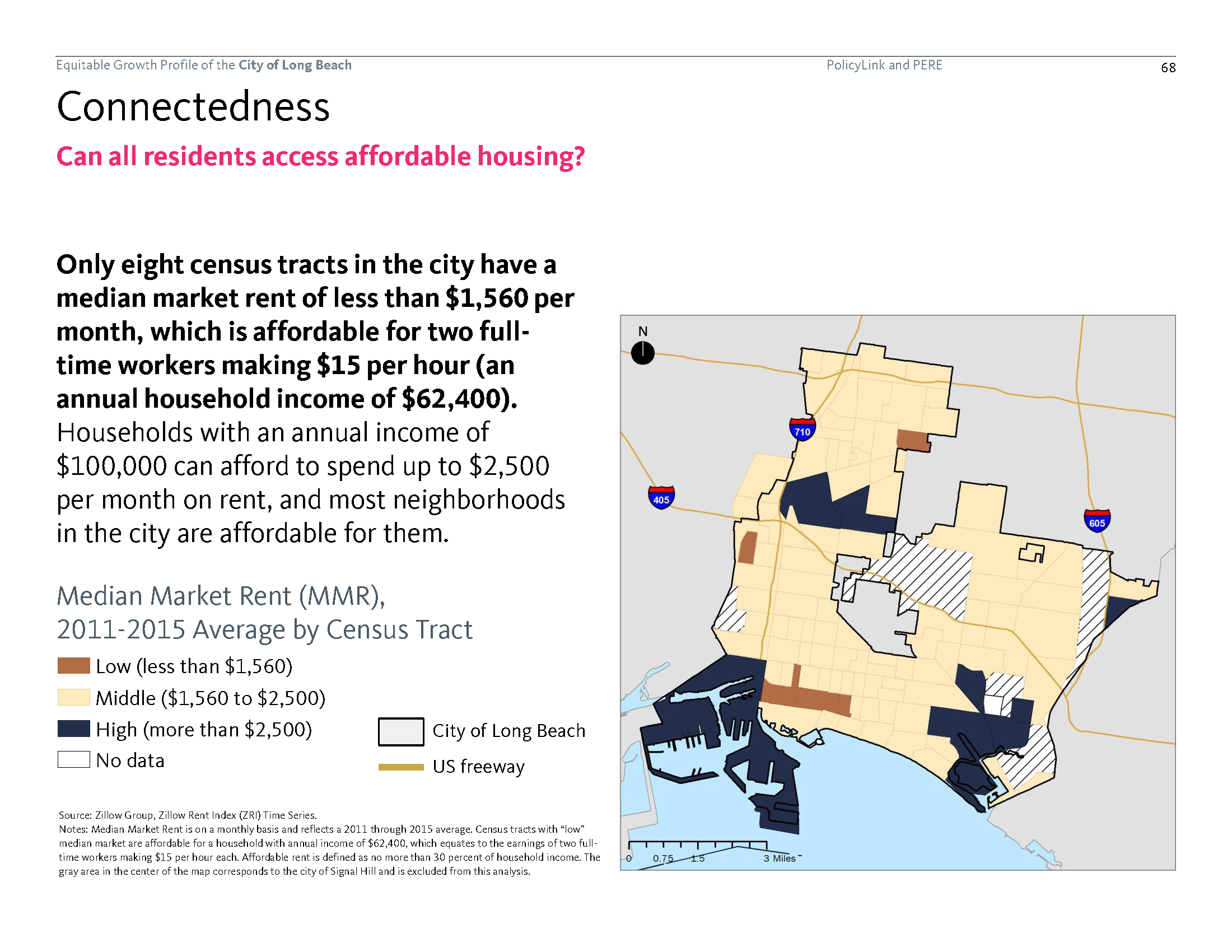

Equitable Growth Profile of the City of Long Beach (pg. 68)

The brown sliver near the bottom of the map roughly correlates with the 90802 zip code, and is a major corridor of Gonzalez’s Council district. These numbers, measuring median market rent from 2011 to 2015, do not account for the last four years of rent growth, meaning one of the city’s only affordable areas five years ago (for two $15/hour, full-time workers, mind you) is now nearing extinction.

It is the downtown area that has suffered the most radical gentrification in this city since 2012, when Long Beach passed the Downtown Plan. The plan opened up 725 acres to new, largely unaffordable development. At the time it was passed, then-Councilmember Gerrie Schipske proposed a motion to set aside a very modest 10 percent of new apartments for low-income residents, but the motion was opposed by other members of the council, including then-Councilmember Robert Garcia, who also voted for the plan.

Responding to concerns over displacement, the Vice Mayor at the time, Suja Lowenthal, said that suggesting the Plan would cause displacement was “fear-mongering.”

“To suggest that this plan invites [displacement] is specious, at best,” she said. “And I’m troubled by that.”

But no bad deed goes unrewarded. Lowenthal is now the City Manager in Hermosa Beach—her salary is over $200,000 a year. Long Beach’s Development Services Director at that time, Amy Bodek, is now the Director of Regional Planning for all of Los Angeles County. Robert Garcia is now the Mayor of Long Beach. Lena Gonzalez, who was a district deputy for Garcia during his time as a Councilmember, is now a Councilmember herself, departing soon for the State Senate. And the Long Beach City Council is now—seven years later—finally implementing some renter protections.

On May 21, largely thanks to Gonzalez, the council passed a Tenant Relocation Ordinance, which will take effect Aug. 1. During that council meeting, the State Senate candidate fought back against calls from other members of the dais to weaken the ordinance.

Back in April, when Gonzalez was also defending the ordinance, she stated that increased protections were especially important for her district, which she cited as being composed of “80 percent renters,” whom she acknowledged are facing ongoing displacement.

Unfortunately, these efforts serve to make a larger blunder of her appearance upon Heineken’s rolling, class-war billboard—especially at a time when Long Beach rents have reached their highest yet.

Tomisin Oluwole

Ode to Pink II, 2020

Acrylic and marker on paper

14 x 22 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Heineken was here

If you inspect the featured picture closely, it’s a bit hard at first to find Gonzalez. She’s barely in the frame, at the top right, wearing, naturally, green. But the image itself is dominated by the monstrous scope of the bus. Even Gonzalez’s campaign banner seems modest, at first glance unnoticed, in comparison to the striking white text of the Heineken ad.

So let’s talk about Heineken. Afterall, Gonzalez would not have had the opportunity to board the wrong bus if Heineken hadn’t decided that high rent and poverty make for a cute ad campaign. So yes, we should always hold elected officials accountable—but why stop there?

Heineken is Europe’s number one beer-producer, and operates breweries in 70 nations. During the height of Europe’s austerity crisis, its chief executive officer opined that Nigeria is “safer” than Greece—and by “safer” he meant “more profitable.”

Heineken adjusts its ads to more effectively exploit different audiences—whose experiences it essentializes and then sells back to as a kind of mirrored mirage. If we assume therefore that Heineken knows rents in California are high, then it means they very consciously chose to exploit that fact with a specific ad to a targeted demographic in the middle of a rent crisis.

Yah, screw you, Heineken.

But while the corporation’s Long Beach slogan apparently centers on ensuring impoverished and isolated renters that they can always count on having six friends in the fridge, one of its recent ad campaigns in Nigeria focused on exploiting family values under the pretense that since Heineken is still operating with a controlling interest held by a member of its founding family, it is still “family owned.” As Fortune magazine explains:

“Until her father’s passing, Charlene [de Carvalho] had no money to her name except a single share of Heineken stock—then worth 25.60 euros, or $32—that her father had given her. Now, as his only child and the sole heir to the Heineken fortune, she was inheriting about 100 million shares, equal to one-quarter of the company’s total stock outstanding. This 25% stake came with voting control, meaning that her single vote outweighed the votes of other investors on any board matter.”

The Fortune piece summarizes this rags-to-riches success story as de Carvalho transitioning from “stay-at-home mom” to “self-made heiress.” I presume it is through a similar alchemy of logic that Heineken’s family values have something to do with Nigeria, that drinking Heineken has something to do with the struggle to pay rent in Long Beach, and that the color green—symbolic of recycling and envy, money and greed—has something to do with the Gonzalez campaign flying their banner on a Heineken bus.

Such a maddening mess of symbolic allusions might appear muddled to the reader, and that’s precisely because corporate culture makes language and lived experience meaningless by co-opting each and then stripping them of their authenticity, purely in the name of profit. Heineken doesn’t give a damn about Long Beach—any more than it cares about high rent, austerity, or family values.

Last year, the brewing conglomerate was forced to apologize for, and remove, a series of ads after one particularly tasteless commercial received enough critical attention. The ad featured a beer bottle sliding down a very long bar past several Black people before gracing the palm of a lighter-skinned woman hanging out with white men. The slogan then appeared: “Sometimes, Lighter is Better.”

To what extent “removing” an ad means anything in a context where it has been eternally preserved online is a great question. As is the question of whether the controversy created by such ads helps or hurts profits. Advertisements that appear ambiguous are created that way on purpose—the double-meaning of a symbol, image, or slogan not only adds to its power, but also leaves its makers ever-innocent. The ad Gonzalez appeared with could be construed by Heineken, or even by the Gonzalez campaign, as a joke, or an ill-advised attempt to relate. That’s because the ambiguity of meaning is always the defense while the clarity of meaning attacks.

In a “free” market economy, such controversy would theoretically lead to consumers taking their money elsewhere. But privilege doesn’t work like that. Privilege means owning your competitors. Privilege means invading a space while claiming that the revenue your invasion generates is what allows that space to exist—something ad-supporters claim about ads. Privilege means corporate manipulators having a laugh at poverty with an ad campaign paid for by the wages of the impoverished.

Conclusion

In case the class dynamics of a gas-guzzling wink-and-nudge from a gigantic multinational peddler of an addictive carcinogen are missed by some—as they were apparently missed by the Gonzalez campaign staff—it would perhaps be worth it for us to end by briefly observing a few of those dynamics, however obvious:

- The ad makes a joke of high rents, as though high rents were an annoying but tolerable symptom of poverty. High rents cause poverty. People are not poor and then suddenly find themselves paying high rent. People have skills, assets, time, intelligence, value, and vision, but have to pay rent before they can use them. (“Rent” in this context means “payment for a location to exist,” not “payment for a structure to be in.”) Rent is theft from the start—the higher it is, the more is being taken from you.

- The ad romanticizes poverty, thus appealing to the myth that poverty is merely a temporary experience to be taken in stride—a part of growing up. But poverty is not an Experience™—bundled together with “finding joy in the little things” and “gaining a new perspective” in an Airbnb listing. Poverty is a global, historical, institutional epidemic caused by private property in land and exacerbated by the greed and domination of various privileged classes. Beer can’t fix that—but beer-makers can certainly profit from it.

- The ad feigns sympathy for renters, pretending to identify with their struggle, and offering up a kind of solace (at a price). Even putting aside any critiques of ads in general, this particular one is condescending and emotionally abusive. It has no place in a city being daily attacked by increased rents.

In solidarity with the struggle of Long Beach tenants, the reader may consider boycotting Heineken, which would mean avoiding “Mexican” Tecate, “Dutch” Amstel, “Australian” Foster’s, “Italian” Birra Moretti, and about 170 other beers. Privilege means no borders.

– – –

Do you have a perspective on Long Beach politics or culture that you’d like to share? We created FORTHE as a platform for the people of our city to voice our experiences and creations, criticisms and dreams. We offer you our collective editorial staff, along with a burgeoning platform, to help you express what matters most. If you have any ideas, or just want to chat about what’s on your mind, shoot an email to andrew@forthe.org, or reach out to @abolishprop13 on Twitter, and let’s make it real.

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org