Emails Show Long Beach Police Pushed to Scrub Racist History from Independent Report

by Kevin Flores | Published May 31, 2020 in Journalism

18 minute readA reference to the Long Beach Police Department’s Prohibition-era ties to the Ku Klux Klan was nixed from an independent report on racial equity after it was published last year, prompting the report to be reissued days later without the passage, an investigation by FORTHE found.

Emails and other records we obtained indicate that concerns over the historical reference stemmed from the police department and the Long Beach Police Officers Association.

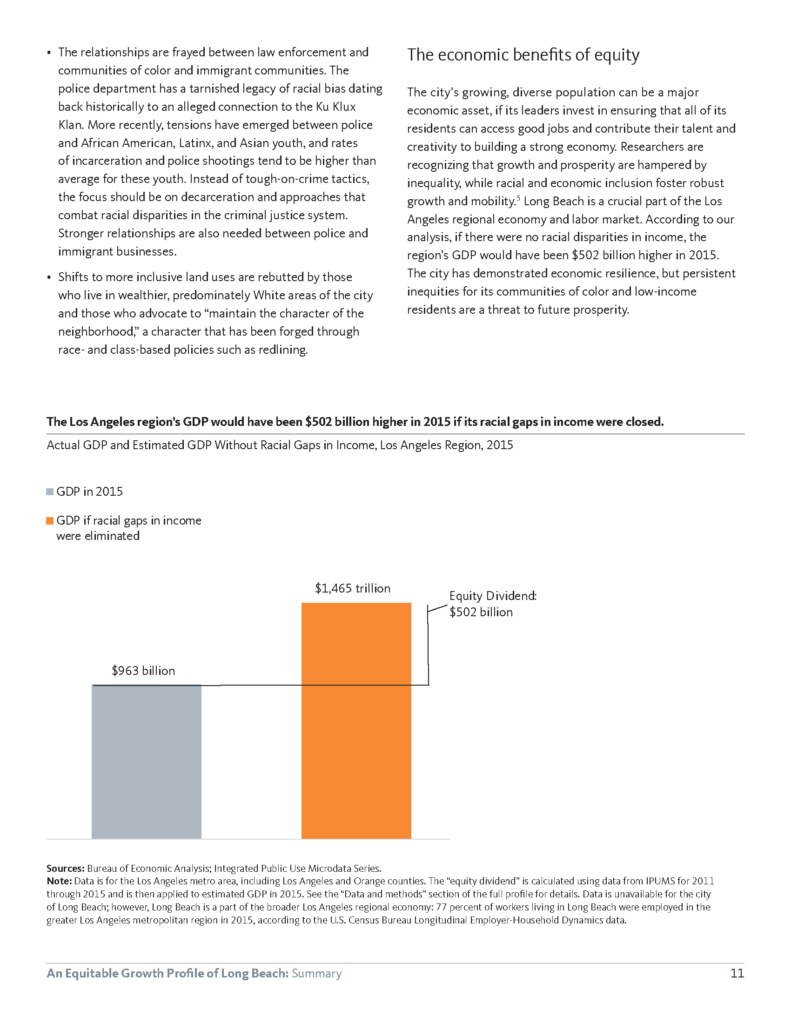

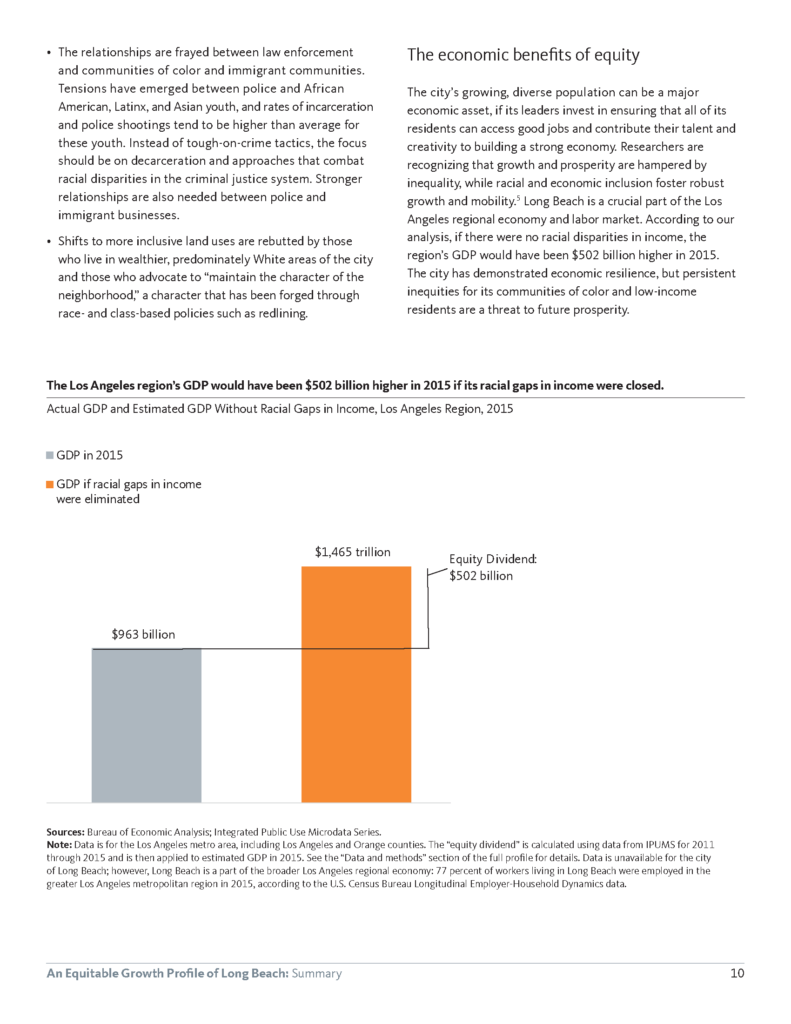

The line in question was contained in a 19-page companion summary of the Equitable Growth Profile of the City of Long Beach, jointly released by PolicyLink and the University of Southern California in February 2019. Before it was removed, the passage appeared in a section discussing relations between the police and communities of color and read: “The police department has a tarnished legacy of racial bias dating back historically to an alleged connection to the Ku Klux Klan.”

Newspaper articles, writings by historians, and archival material from the 1920s we reviewed confirm that connection, which was true of many police departments in the state at the time, as Klan recruiters specifically targeted law enforcement officers. The Long Beach Daily Telegram reported in 1922 that local KKK membership ledgers contained the names of numerous LBPD officers. Two years later, multiple newspapers reported on allegations that LBPD officers dressed in Klan garb had tortured three Black teens on the outskirts of town.

READ THE COMPANION PIECE TO THIS ARTICLE • Hoods and Badges: A Look Back at How the KKK Infiltrated the LBPD in the 1920s.

The pressure from the police department to whitewash this history put researchers in an unprecedented and unusual position, according to PolicyLink Senior Associate Jamila Henderson, who said the line was originally included in the report because community members interviewed by researchers cited the history as a reason why they felt wary of police.

“It was a hard decision. We hadn’t really been put in that position before,” she said.

Ultimately, the line was removed and a new version of the document was published. Community members, some of whom were involved in the report’s creation, expressed frustration at the line’s removal.

“Let’s acknowledge our history, our full history. And part of that is the past relationship between the (police) department and the Klan,” said Black Lives Matter Long Beach organizer Dawn Modkins.

This comes at a time when some cities are explicitly acknowledging the racist acts committed by their police and even paying reparations to the victims of bigoted police violence.

Recently, the Stockton Police Department teamed up with a historian to integrate the department’s history—good and ugly—into its training.

Criminal justice researchers Samuel Kuhn and Stephen Lurie, who piloted a “racial reckoning” program at a handful of law enforcement agencies across the nation, say the trust-building process between police departments and communities of color must start with a shared understanding of the past, including the uncomfortable parts, which influence present-day institutional discrimination.

“The reconciliation process attempts to directly address both the current and the historic relationship between minority communities and law enforcement that serves as a backdrop to daily interactions and the periodic flare-ups that continue to embroil American cities,” the pair wrote in a 2018 report on the topic. “Owning and condemning past harms aligns the values of police with community.”

‘TALE OF TWO CITIES’

Back in November 2017, Councilmember Rex Richardson asked his colleagues to give the go-ahead to a landmark report that would measure how fairly the local economy was distributing wealth and resources across different demographics.

This was an effort that had been in the works for some time, and would come to be a cornerstone of Richardson’s Everyone In initiative. He believed the findings would provide a view of the local economic landscape through a social equity lens, something that was necessary to inform future conversations around economic inclusion in the city.

“For years we hear this term when we talk about Long Beach: ‘the tale of two cities,’” Richardson said from behind the dais the day of the vote. “And we’ve attempted many times to address that, close the gap, address the equity, but really this is the piece that I see that allows us to track and see how we’re doing over time.”

The council proceeded to vote unanimously in favor of producing the report.

In accordance, the Office of Equity—under the auspices of the Health and Human Services Department and ultimately the City Manager—was tasked with coordinating a partnership between a philanthropic entity and a research institute that would result in an economic equity profile of the city.

Brought on to tackle the research end were PolicyLink, an Oakland-based progressive think tank, and University of Southern California’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity.

Over the next year, researchers crunched figures from a vast array of sources, disaggregating data by race, income, and other indicators on topics such as employment, housing, and education.

Ultimately, two documents were produced: a full-length economic equity profile of the city and a slimmer 19-page profile summary.

Apart from highlighting the key points of the profile, the summary contains insights the researchers gleaned from over 20 interviews with community leaders about the concerns plaguing underprivileged communities in Long Beach. It also provided recommendations the city could adopt to help alleviate economic inequities.

Once a draft of the profile and summary had been prepared, there was a back-and-forth editing and planning phase between the researchers and the Office of Equity, emails we obtained through a public records request show. That process ultimately resulted in the profile summary that would initially be released to the public.

During a Feb. 5, 2019 launch event at Long Beach City College, attended by various community leaders and public officials, hard copies of the summary were handed out to audience members.

Equitable Growth Profile Event Launch happening now @policylink @PERE_USC @EquityLB #EquityLB #EveryoneIn @RexRichardson pic.twitter.com/DID3JcfPs4

— Long Beach Health (@LBHealthDept) February 5, 2019

“We need to focus not on the disadvantaged but on the structurally disempowered.” @Prof_MPastor 🙌🏾✊🏽 at the @LongBeachCity @USCDornsife @policylink Release of the Long Beach Equity Profile with support from @Citi Community Development pic.twitter.com/DpItH1TSZY

— James Alva (@JamesAlva) February 5, 2019

The researchers’ findings in many cases are eye-popping, though not surprising to those living in the often-neglected parts of town. Graph after graph shows entrenched disparities between the city’s white population and its Brown and Black residents in terms of wealth creation and economic opportunities.

Despite the city having a majority-minority population, the profile revealed that Black men are twice as likely to be unemployed than white men. It also showed that minority-owned businesses on average have significantly lower annual receipts than their white counterparts (10 times less in the case of Black-owned businesses). Researchers also found that indigenous and mixed-race residents have a life expectancy that is seven years below the city average.

By all appearances, the project had been a success.

But two days later—according to emails and digital metadata we inspected—a new profile summary was created and later quietly uploaded to the PolicyLink website. A side-by-side comparison between the original and the second version reveals two glaring omissions.

Gone is a foreword from the City of Long Beach penned by Equity Officer Katie Balderas of the Office of Equity.

Also gone is the line from page 11 that mentions the LBPD’s former “connection to the Ku Klux Klan.”

So what happened?

‘FALLOUT’

Behind the scenes, the first run of the profile summary had agitated certain parts of City Hall.

The City Manager’s Office—then headed by Pat West, who resigned in September—took issue with two aspects of the profile summary, according to city spokesperson Kevin Lee.

For one, city management felt that Balderas’ foreword gave the summary—which did not exactly paint a rosy picture of the city—the appearance of an official city report.

“The City does not make a practice of providing forewords for publications that are not City publications. This is what happened in this case,” said Lee. “The report and recommendations are those of PolicyLink and not the City of Long Beach.”

A memo making that last point crystal clear was fired off to the City Council the same day the second version of the summary was uploaded to the web.

“The research and report … reflect the opinions and recommendations stemming from data and interviews with community members. These were not approved by the City of Long Beach and are not to be considered recommendations and statements from the City of Long Beach,” the memo stated.

The whole debacle seemed to have caused some amount of interdepartmental strife, emails show.

Tomisin Oluwole

Dine with Me, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

“I am still treading lightly here to see what (if any) additional fallout there will be. It seems to have settled down once we submitted this memo to Council,” wrote Balderas in a Feb. 14, 2019 email to the PolicyLink team.

In the end, Balderas, who did a substantial amount of legwork to get the equity profile off the ground, was forced to remove her name and her foreword from the document.

She did not return a message seeking comment for this piece.

You can read the now-removed foreword below.

Another of city management’s criticisms of the profile summary related to the line referencing the LBPD’s historical ties to the KKK, according to Lee. He said city management sided with cutting the line because it “was not supported by context or data, and does not represent the Long Beach Police Department as it stands today.”

Pressed further as to who exactly made the original request for the edit, Lee said, “The Long Beach Health and Human Services department … also saw the claim that did not include support or context. The Health department made the request to have it removed. I believe that was a phone call. I’m not sure if there was any follow up on the subject. Then PolicyLink made the decision to remove it.”

However, emails discussing the project shortly after the cuts were made indicate that the request came down from the police department.

“We were happy with the partnership and are disappointed about how this turned out, particularly since we took swift action to address the concerns from the police department,” PolicyLink Managing Director Sarah Treuhaft wrote to Balderas on Feb. 13, 2019.

Reached by email, Treuhaft clarified that the concerns from the police department about the line were indirectly relayed to PolicyLink by the Health Department.

The LBPD did not return a request seeking comment on the matter.

Below you can compare the section where the line was cut in both versions of the report.

‘A HARD DECISION’

Henderson, the profile’s primary author, called the city’s request “odd.” In an interview last year, she said she had never before been asked to nix information from a report once it was published. PolicyLink has produced these types of equity profiles for numerous jurisdictions nationwide.

The Long Beach Police Officers Association also waded into the controversy, sending a letter to PolicyLink three days after the launch event expressing concern about how police were being portrayed in the summary.

In an email to FORTHE Media, LBPOA President Jim Foster confirmed the letter was sent and characterized the line in question as a “surprising remark.”

“I found that the comment was grounded on what appeared to be an unfounded allegation against a chief of police in 1922, nearly 100 years ago. To my knowledge, no one has ever substantiated the rumor, but clearly any connection between the KKK and our current police department seems to be farfetched,” Foster said.

However, he stressed that “we at LBPOA had nothing to do with (the line’s) removal.”

In the letter, which we obtained via a public records request, Foster questioned the methodology used to arrive at the conclusion in the disputed line. He also cites “two professional polls” conducted by a “validated polling company within the last few years that asked about the favorability of our police department.”

He went on to write that both of those polls showed that the LBPD “had a favorable rating across all demographics citywide.”

“I’m confident you must have used a certified source, otherwise this statement would really be nothing more than a wild supposition based on random interviews,” he wrote to Henderson about the controversial passage.

You can view the full letter below.

Henderson said the line was not included in the summary haphazardly. It was inserted only after the local history surfaced in researchers’ interviews with community members and was confirmed later on by historical records, she said.

“We’re not going to include information (in the summary) if just one respondent mentioned it. It has to be more of a common theme across respondents,” Henderson said.

Asked about the significance of the line, Henderson said: “I think if there’s a fear that community members (have) when interacting with police and that there’s this long-standing sentiment of the police having been associated with the KKK, that can really make it difficult to move forward and to bring about any type of resolution or change. It seemed (to be) something that resonated and ultimately was included in the summary.”

However, with police brass and city management rankled, the team at PolicyLink relented and pulled the line because they didn’t want the controversy to become an issue that would detract from the rest of the report, Henderson said.

The leftover stacks of the original hard copy summaries were stashed away and a new version was published without notice.

‘I’M USED TO IT. I’M NOT SURPRISED…’

In an interview in July, Councilmember Richardson said he had not been aware of the stricken portions in the profile summary and was not involved in the minutiae of the report’s creation.

“So, the Office of Equity went ahead and began the process of working with PolicyLink and others to get the study done. From there, my job kind of stops for a little until the product is delivered,” Richardson said.

Told about the changes to the profile, he likened them to the normal editing process that all reports go through. However, the changes in question were made to the published profile summary and not a draft copy. In the end, he says he was happy with how the project turned out and believes it will be a useful tool for the city in its endeavors to close demographic gaps in the economy.

“I mean, for all intents and purposes, the data shows the story that we asked for,” he said. “And I think that’s the real story of the profile. Now, how many iterations they went through—they’ve never been asked to do this before. Of course, there’s gonna be some drama.”

Others did not feel the same about the edit.

“I think the story here is the fact that the city is doing what it always does: It wants to control the narrative, wants to play public relations and censor,” said Modkins.

She pointed to the TigerText scandal and the mass destruction of police misconduct records in 2018 as examples of what she said is the LBPD’s tendency of keeping the public in the dark.

“There was supportive context because it was based on interviews with over 20 people or 25 people; the same people that were interviewed for the rest of the context of the report. So why is the rest of the context accepted, but not that piece about the Klan?” Modkins said.

Although she was not officially interviewed for the report, Modkins said that she was in contact with some of the interviewees while the report was being put together in 2018.

Claudine Burnett, the former head of the Literature and History Department of the Long Beach Public Library, trawled through reams of archival material in putting together her book Prohibition Madness: Life and Death in and Around Long Beach, California 1920-1933, which includes a section discussing the KKK’s activities in the city.

“It angers me, that angers me, but it has to be seen in perspective,” said Burnett about the decision to delete the passage.

She said that if the city wanted to temper the line, it could have asked for it to be changed to add more context instead of wholesale removal.

“If they edited the remark to say something to the extent of, ‘Like most other cities in California during the 1920s, Long Beach police as well as other police departments supported the KKK,’ that would be true, but it wouldn’t just single out Long Beach.”

Rev. Osie Leon Wood Jr., who was one of the community leaders interviewed by the research team that put together the profile summary, cast the whitewashing of local history in the profile as part of a broader national aversion to confronting uncomfortable aspects of the past.

“I’m used to it. I’m not surprised. I’m not hurt. I have never, in any part of America, have known America to deal with the real issue (of racism) in a way that really puts it on the table,” said Wood. “We’ve always had some kind of an excuse or some kind of an oversight or different set of words.”

And while the history is a century old, Wood says that it is still highly relevant.

“One hundred years isn’t that far back. I’m 79. I was born at the last of Jim Crow (laws),” he said. “You’re talking to a man who in my house I have a rocking chair of a lady who was a former slave who used to rock me when I was a little bitty boy. So it’s not that long ago when you think about it.”

READ THE COMPANION PIECE TO THIS ARTICLE • Hoods and Badges: A Look Back at How the KKK Infiltrated the LBPD in the 1920s.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores