Hoods and Badges: A Look Back at How the KKK Infiltrated the LBPD in the 1920s

by Kevin Flores | Published May 31, 2020 in Journalism

19 minute readThe original iteration of the Ku Klux Klan was started by Confederate veterans in Tennessee and spread throughout the war-torn South during the Reconstruction era. These armed white supremacists inflicted terror and violence upon Black people and their allies during so-called nightrides and riots in an effort to maintain the antebellum racial hierarchy.

The group was responsible for thousands of murders during this period. Partly due to intervention from the federal government, the hate group disbanded and splintered off by the 1870s.

But that would not be the last of the hooded order. In the early 20th Century, the country saw a massive revival of the KKK, which at its height would count several million people among its ranks.

The second iteration of the KKK was galvanized into existence by the 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation—a racist, revisionist take on the Civil War filmed and premiered in Los Angeles.

The massive movement spawned by the film was in large part a reaction to a surge in immigrants to the U.S. during this period. Those who arrived in California were mainly from Latin America and Japan.

The newly revived KKK was “an emotional reaction to diversity that sees diversity as really threatening, and that’s what fed this kind of patriotism,” said Linda Gordon, author of The Second Coming of the KKK, during a talk last year.

The organization portrayed itself as a vigilante force that would fight against anyone deemed not to be a quote-unquote real American. The Klan’s hateful doctrine contained not only xenophobia, but religious bigotry, restricting membership to White Christians. Their vision easily infiltrated Protestant denominations, which at the time felt threatened by the liberalization of social norms.

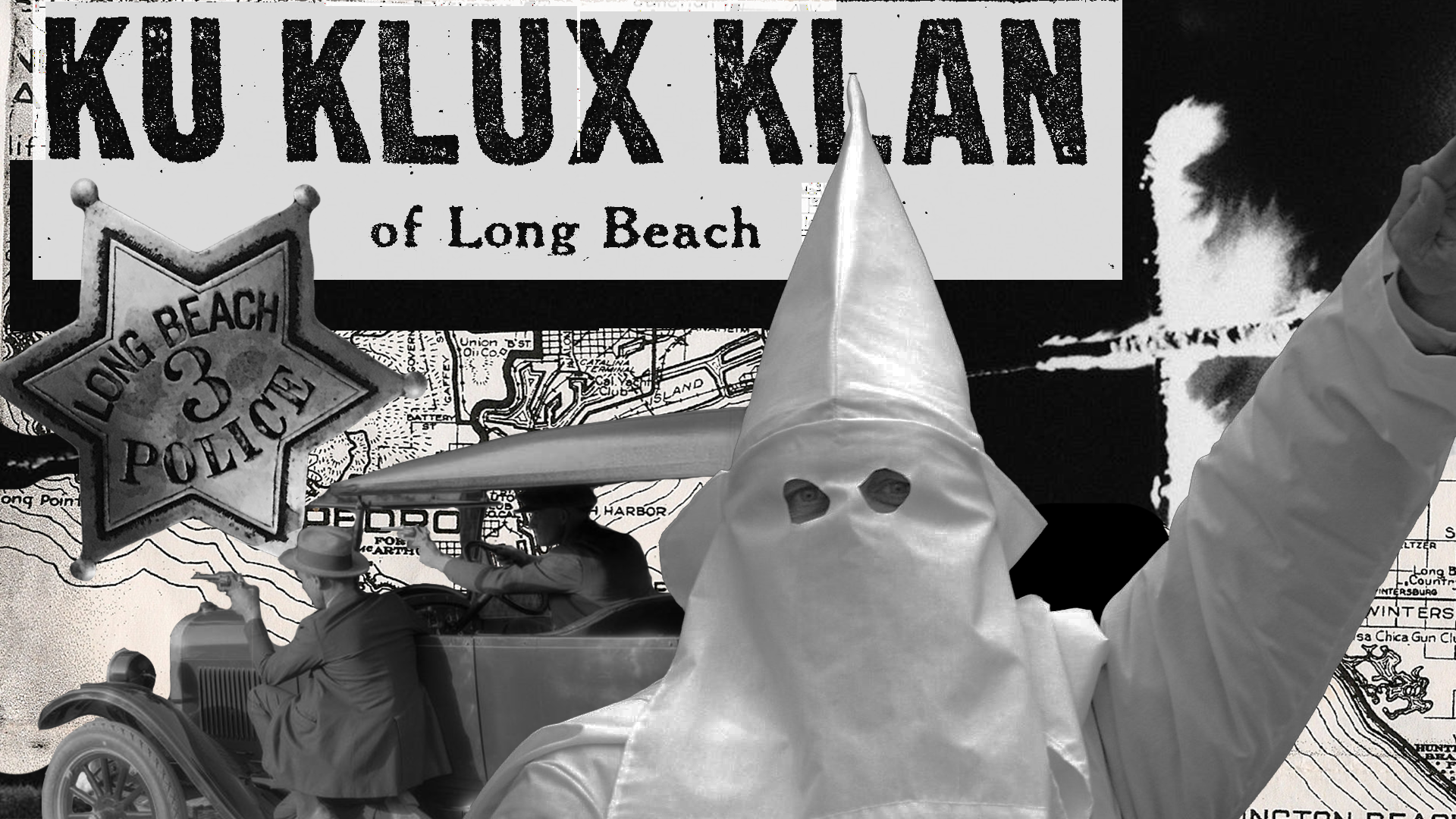

This is what happened in Long Beach, where the KKK’s resurrection bubbled up from the local Christian temperance movement that seized upon the anxieties of White Protestant Midwestern transplants, writes local historian Claudine Burnett in Prohibition Madness: Life and Death in and Around Long Beach, California 1920-1933. Fear that the “sins” of bootleggers and flappers were destroying the nation’s moral fiber begot an “America for Americans” mindset that subordinated minorities and anyone perceived to be unpatriotic.

In 1922, one of the hate group’s officers told a Daily Telegram reporter “that the Ku Klux Klan is one of the purest, noblest, cleanest, most Christian, most patriotic organizations that had ever come to existence.”

During this time, the KKK had an office at 1630 E. Anaheim St., in what is now Cambodia Town. From there, they mounted right-wing populist appeals to Long Beach’s White working-class with rhetoric pushing the idea that they, not immigrants, deserved jobs in the city’s booming oil industry, writes Letticia Montoya in The Ku Klux Klan in Long Beach, a Cal State Long Beach research paper held by the city’s historical society.

As a way to protect and forward the organization’s interests, the local KKK chapter successfully recruited city officials, including police officers.

“By day, some Klansmen exchanged their hoods and sheets for blue coats and badges as Klan membership was especially popular in the Long Beach Police Department,” then-graduate student Billy Norfleet Jr. wrote in a 2004 article for the now-defunct Long Beach literary journal The Southlander. “Indeed, the Klan headquarters on East Anaheim Street and the cross-burning ceremonies at Recreation Park … made Long Beach a ‘tough place for Blacks.’”

While Long Beach was something of a regional hotbed for the KKK—as was Anaheim 10 miles to the east—it was by no means the only city in the state at the time to see members of the white supremacy group donning a badge.

In his book Power on the Right, former-FBI-agent-turned-author William W. Turner notes that the organization’s leaders “took particular pride in emphasizing the large number of law enforcement officers … that had joined their order.” This was largely done as a way to legitimize the group’s activities.

“The police chief and police judge in nearby Bakersfield were both members, as were seven Fresno officers, twenty-five cops in San Francisco, and about a tenth of the public officials and police in the rest of California’s cities,” Columbia University history professor Kenneth T. Jackson writes in The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930.

Jackson included Los Angeles Police Chief Louis D. Oaks and Los Angeles County Sheriff William Taeger as high-profile members of the Klan who were outed in 1922.

Southern California in general had the second largest concentration of Klan chapters and members outside of the South during this period, writes Robert Salley in his 1963 dissertation Activities of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Southern California, 1921-1925.

When then-Long Beach City Manager Charles Hewes obtained ledgers containing the names of people belonging to local KKK divisions, he announced that among them were 180 Long Beach residents, including “several Long Beach policemen and firemen,” according to the May 4, 1922 edition of the Long Beach Press.

The Long Beach police chief at the time, Ben W. McLendon, actively tried to root out the Klan from the force and issued a bulletin warning officers that joining the Klan would cost them their jobs.

In it he wrote that the KKK was attempting to recruit officers for the purpose of “shielding violence, un-American and unlawful acts.”

Soon after, one motor officer who reportedly refused to renounce his membership to the KKK was suspended indefinitely.

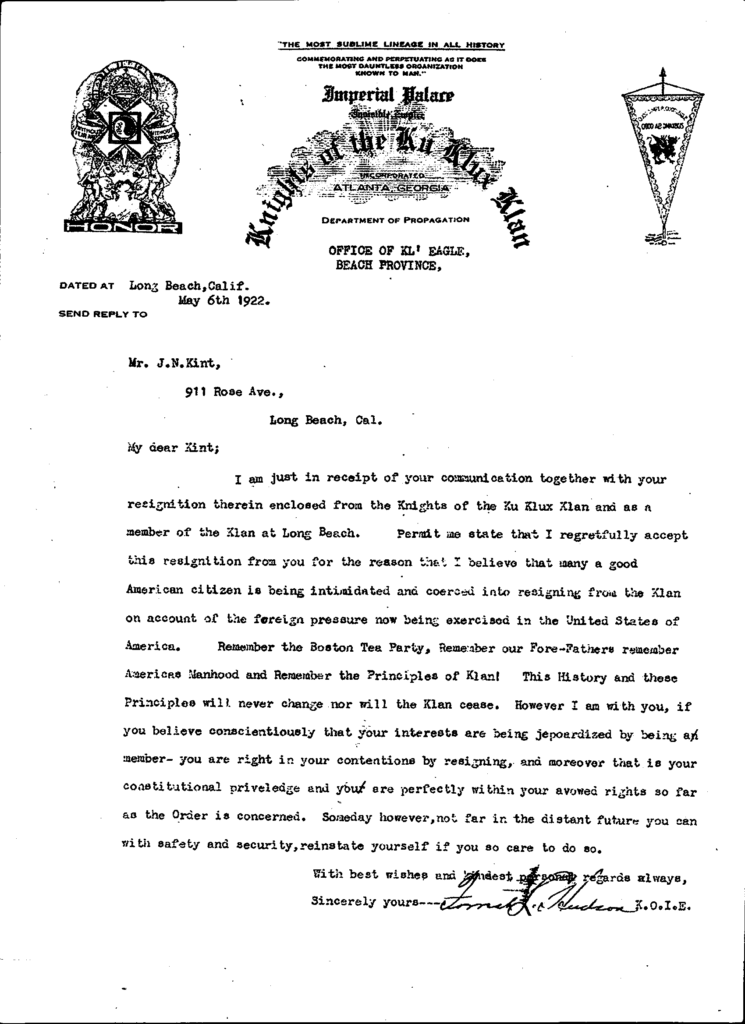

LBPD Officer J.N. Kint took a different tack and hung up his robe. In a letter addressed to him, a recruiter for the local KKK outpost regretfully accepts his resignation, but not before assailing the “foreign pressure” that was coercing members to quit.

McLendon would end up proposing a city ordinance that would outlaw gatherings of masked people in Long Beach without written consent from the City Council before the state adopted a similar antimask law the following year.

In contrast, Hewes had a softer response to the KKK’s infiltration of the police department, saying he would only fire a police officer who was a member of the Klan if the organization’s secret oath was found to contradict the department’s oath.

“I don’t propose to interfere with a man’s personal rights, as long as they don’t clash with his official duty. I shall go easy on this matter and see what has been done,” Hewes said in a statement to the Daily Telegram on May 4, 1922.

Without Hewes’ support, McLendon’s attempts to stomp out the Klan from public positions would eventually lead to his downfall.

When KKK members attempted to disrupt a political gathering in late 1922, McLendon ordered the arrest of some of the hate group’s higher-ups, which included two of the city’s ex-police chiefs—Charles Cavender Cole and James I. Butterfield. This created a firestorm that led to McLendon being suspended and demoted by Hewes, and eventually arrested, even though reports at the time show that the fallen chief was popular among residents.

In fact, by this point some Long Beach residents had become fed up by the activities of the Klan. That May, in an exasperated letter to the LA Times, one man had asked newspapers to publish “the names of the two or three hundred citizens in Long Beach who have that kind of manhood that is willing to cloak itself behind the veil of secrecy.”

Nonetheless, the ouster of McLendon energized the KKK and its presence in the city would eventually balloon to 10,000 strong, writes Burnett in Prohibition Madness.

While the KKK always contained its original thread of anti-Blackness, there weren’t many African Americans living in Long Beach at the time, less than 150, according to the 1920 Census. This didn’t stop the hate group, which also aimed their antipathy toward Catholics, communists, labor unions, tipplers, as well as Mexican and Japanese immigrants.

Many historians argue that the KKK of this era was not as explicitly monstrous as their forerunners and were more apt to engage in intimidation through political machinations, threats, and shows of force rather than actual acts of violence.

Charlotta Amanda Bass, the publisher of the California Eagle, an African American newspaper at the time, recalled to Salley in an interview that the Klan would parade near the Central Avenue District in Los Angeles in an attempt to terrify the predominantly Black residents of the area.

However, there were some reports from around the state of the hooded fraternity committing violence during this period. Across the bay in San Pedro, the group formed a mob in the summer of 1924 that stormed an Industrial Workers of the World union hall. The mob tarred and feathered various dockworkers and scalded their children with coffee.

But one particularly dark allegation that same year, said to have involved members of the LBPD, has received considerably less attention.

OFFICERS ACCUSED OF MOCK LYNCHING

On Nov. 18, 1924, three Black teenagers were pulled over by LBPD officers. The vehicle the trio were riding in had been reported stolen, according to newspaper reports at the time.

Tomisin Oluwole

Ode to Pink II, 2020

Acrylic and marker on paper

14 x 22 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

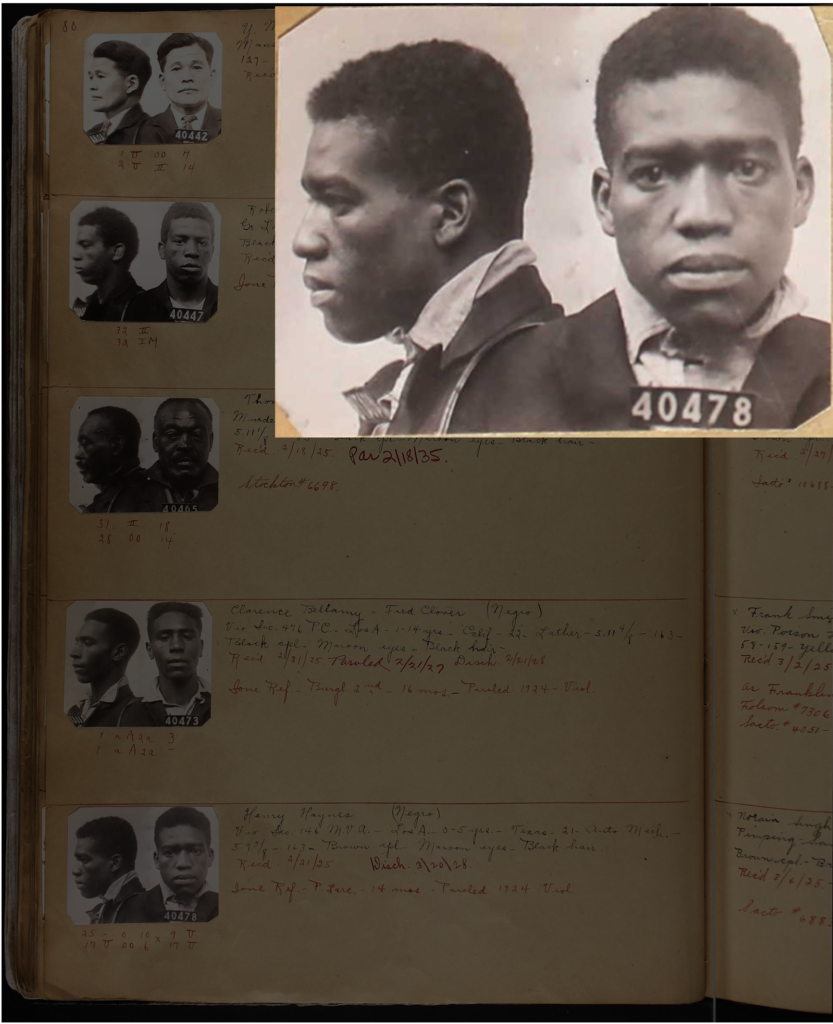

When the patrolmen searched the car, they allegedly found a saxophone, a watch, and other property that police said tied the boys to a string of burglaries that had recently occurred around the city, according to various media reports. The three suspects, George Rice, 18, and brothers Sam, 17, and Henry Haynes, 18, were arrested and taken to the Long Beach municipal jail downtown.

According to the LA Times, the teens said that night while locked up, two officers took them from their cell to a marshy, undeveloped area on the outskirts of town known as the Willows, in what is today the Wrigley District. They were led to a desolate spot that served as a police shooting range, Rice and the Haynes brothers said.

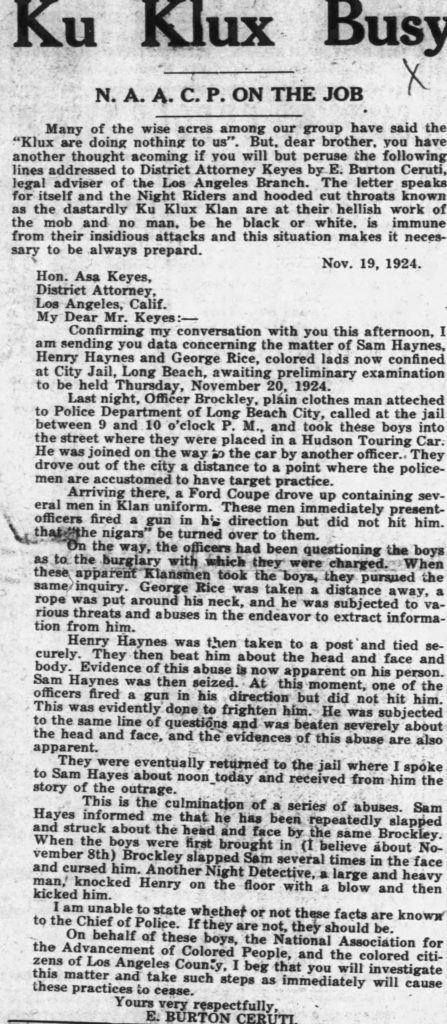

A letter to then-Los Angeles County District Attorney Asa Keyes from NAACP civil rights attorney E. Burton Ceruti, who interviewed the teens, was published in the California Eagle, an African-American newspaper, on Nov. 21, 1924 and recounted the horrors that followed.

According to the document, a Ford coupe pulled up carrying several men in Klan garb, also said to be police officers. The hooded figures quickly took possession of the teens, referring to them as “the nigars,” the letter reported. Ceruti wrote that the Klansmen proceeded to torture and question the young men about the alleged burglary:

“George Rice was taken a distance away, a rope was put around his neck, and he was subjected to various threats and abuses in the endeavor to extract information from him.

Henry Haynes was taken to a post and tied securely. They then beat him about the head and face and body. Evidence of this abuse is now apparent on his person. Sam Haynes was then seized. At this moment, one of the officers fired a gun in his direction but did not hit him. This was evidently done to frighten him. He was subjected to the same line of questions and was beaten severely about the head and face, and the evidences of this abuse are also apparent.”

Despite the terror described by Ceruti, Rice and the Haynes brothers refused to proffer a confession to their captors. This was reportedly met with threats to lynch and “burn them at the stake,” according to the Times.

Eventually, the teens were returned to the jail where they received medical care for their wounds. Centuri wrote that this was only the latest instance of police brutality inflicted upon the trio, who had previously been slapped, punched, and kicked by Long Beach police, imploring Keyes to investigate the matter and to take steps that will “cause these practices to cease.”

Keyes found the claims credible enough to order the Los Angeles County grand jury to launch an investigation.

This wasn’t the District Attorney’s first bout with the hate group. Two years prior he been part of the prosecution team that brought 36 KKK members before another grand jury for raiding and ransacking the Inglewood home of Basque immigrants suspected of bootlegging. The vigilantes were indicted by the grand jury, however, none were ultimately convicted in superior court.

Then-LBPD Chief Jas Yancy—McLendon’s successor—“doubted the accuracy of the charges” levied by Rice and the Haynes brothers, saying that the case against the suspected burglars was so strong that there had been no reason to force a confession, according to a report in the Daily Telegram on Nov. 26, 1924.

In what now appears to have been a likely attempt to gaslight their way out of the allegation, the local Klan chapter offered a $250 award to anyone who provided information that led to the arrest of the perpetrators of the alleged torture and an additional $250 if evidence was provided showing that anyone involved was a member of the hate group.

Over the course of a week, various witnesses were called to testify in the probe, including LBPD detectives Norman J. Brockley and Walter A. Jensen, who handled the robbery investigation, and Jailer Fred L. Morrison, according to an article in the Daily Telegram. The reporting from the time is not clear about what officers were accused of the beating. The same Daily Telegram article also mentions a set of “arresting officers” also summoned to testify, but does not name them. One of them could be motorcycle policeman Brooks L Gibson, who was identified as a witness in an LA Times article.

On Dec. 2, the all-white grand jury “referred the matter to a committee to draw up a report,” the LA Times reported. Coverage fell off after that and it’s unknown what became of the report or if one was even produced. There’s also no indication that any of the officers implicated in the accusations ever faced any consequences.

Brockley was forced out of the department in 1925 due to an unrelated matter, the LA Times reported. Gibson died in a motorcycle crash, along with his wife, in 1930, Burnett writes in Prohibition Madness.

On the other hand, after pleading not guilty, the Haynes brothers were convicted of burglary and sentenced to jail, with Henry receiving a sentence of over four years at San Quentin State Prison, court records from the time show. Little is known about the fate of Rice.

THE KLAN FINDS POLITICAL SUCCESS

KKK activity in the city continued to increase in the years that followed, as its influence wormed its way into the city’s political circles.

Several local newspapers published accounts of surreptitious Klan events in the city, one of which was accompanied by photos depicting a crowd of ghostly robed and hooded figures gathered in the cover of night around a giant burning cross at Recreation Park.

In 1926, the California Klan’s annual convention was held in Long Beach in which 30,000 Klan members openly marched down Ocean Boulevard—about 5,000 of whom were local, according to Burnett’s book. The procession was “spectacular in the extreme,” reported the Santa Cruz Evening News—organizers had gone so far as to have a plane fly overhead with a shining red cross attached to its fuselage.

The Long Beach Chamber of Commerce even provided custom metal badges to some participants.

This event would not have taken place without the approval of city leaders, who if not sympathetic to the cause, were outright members themselves. “In the 1920s and again in the late 1930s, Long Beach’s most influential leaders were members of the Klan,” writes Laura Rosenzweig in her 2013 dissertation Hollywood’s Spies: Jewish Infiltration of Nazi and Pro-Nazi Groups in Los Angeles, 1933-1941. She goes on to write that the “Klan was an important node in the city’s commercial network.”

Others note that both Klan members and LBPD officers became union-busting instruments wielded by local elites at the time.

“In Long Beach, real estate and port interests relied on the Long Beach Police Department and the Ku Klux Klan to suppress union organizing,” write CSULB professors Gary Hytrek and Alfonso Hernández-Márquez in their article Path Dependency and Patterns of Collective Action: Space, Place, and Agency in Long Beach, California, 1900–1960.

The local chapter of the KKK even raised funds in the 1920s to build Community Hospital out of a desire to have a “White hospital” as an alternative to the public Seaside Hospital and the Catholic St. Mary’s Hospital.

Despite such ubiquity, KKK chapters in Southern California began seeing their membership dwindle around 1925, mostly due to internal rifts and anti-Klan activism and legislation.

“Long Beach Klan Termed Dead” read a 1925 Los Angeles Times headline, which described the disbanding of the Long Beach Klan No. 11 due to a “falling off in membership.” Rifles were later found and seized by police from the organization’s Anaheim Street headquarters.

By the turn of the decade, the KKKs local rank-and-file numbers had dwindled even further. But this did not mean the Klan ideology withered away completely. The hate group’s electorate strategy had successfully placed members and sympathizers into public office across the nation from the local to the federal level, some of whom openly ran on xenophobic platforms.

A 1933 letter from the California Grand Dragon Klan leader thanking the Long Beach City Manager for helping the organization secure the Municipal Band for one of its meetings illustrates just how normalized the relationship remained between white supremacists and Long Beach city government officials well into the next decade.

Others slipped into the system more surreptitiously. The KKK badge of Long Beach Mayor Oscar Hauge, who was elected in 1927, lies in a Long Beach Public Library vault. Hauge was not ousted as a member of the hooded order while in office, Burnett writes, and later went on to become a Los Angeles County Supervisor, a post he held from 1938 to 1944.

This second incarnation of the KKK officially folded in 1944 after much scandal and mismanagement.

In more present times, the hate group has on occasion reared its head locally. At the height of the Civil Rights movement, the Klan made efforts to recruit members within the city, distributing thousands of “business cards.” In 1965, KKK members threatened to turn the Off-Broadway Theater, then on Lime Avenue, into a “pit barbeque” when one of their productions featured a mixed-race cast, the Los Angeles Free Press reported.

White supremacists attempted to infiltrate the punk scene in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and would show up at Southern California music venues, such as the long-gone Fender’s Ballroom in Long Beach, but were roundly rejected by the scene.

Last year, the letters “KKK” were seen scrawled on a bench at Pan American Park in the Lakewood Village neighborhood hours before 57-year-old Frederick Taft was shot to death in a park bathroom. It remains unclear if the murder was directly connected to the hate group because the crime remains unsolved. Nonetheless, the Taft family believes it was a hate crime.

Today, the KKK is fractured among numerous independent chapters that use the name, one of the most prominent being the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which is classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Altogether, the SPLC estimates that there are between 5,000 to 8,000 Klan members nationwide, though hate groups in general have been on the rise in the last few years.

Updated 9/23/21 with newly uncovered letter from NAACP civil rights attorney E. Burton Ceruti to Los Angeles County District Attorney Asa Keyes.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores