“Suffrage is Unfinished Business”: Equality Activist Zoe Nicholson Wants You to Know That Women Are Still Not in the Constitution

Local elder’s 40-year fight for equality highlighted in a new documentary premiering Monday at SXSW

33 minute readWhen the USA Women’s Soccer Team reached a multi-million dollar settlement in its class action lawsuit for equal pay last month, local author and equality activist Zoe Nicholson applauded them for their “persistent hard work” over the course of the six-year legal battle. While celebrating the tenacity of the team and the subsequent victory, Nicholson could also not help but note that if the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) had been added to the Constitution by now, which codifies protection against discrimination based on sex or gender into law, equal pay “would [already] be universal.” If or when the ERA is ever officially added to the highest law of the land, it would be officially unconstitutional to pay women less than men for the same job.

Nicholson has dedicated the majority of her life to getting the 24-word amendment federally ratified—or to die trying. It has been a spiritual, political, and community-building calling for her, and something she sees as a necessity for true equity in the United States. As someone who offers ERA 101 presentations, Nicholson laments that most Americans are unaware that the ERA has never been ratified, or just how relevant it still is to our time. As she often explains in her talks, despite women having the right to vote, “suffrage is unfinished business” because women are still not fully protected by the Constitution.

Unfortunately, an allegedly unconstitutional deadline tacked on by Congress in the seventies remains a formidable barrier. But, thanks to the ratification by 38 states and a bill to rescind the deadline, there is a renewed hope that the ERA could be added to the Constitution prior to its 100th birthday in 2023.

Nicholson’s 40-year involvement in the struggle is highlighted in a new documentary titled “Still Working 9 to 5,” premiering March 13 at SXSW 2022 (South By Southwest Concert & Festivals). Focusing on how little has changed since the debut of the classic office comedy “9 to 5” (1980) in regard to the prevalence of sexism in the workplace and other sectors of society, the film also gives Nicholson a wider platform to make a case for the ERA.

In addition to hopefully hobnobbing with national treasure Dolly Parton (she starred in the film with icons Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, and they are all featured in the documentary), Nicholson is excited to have the significance of this amendment that is so near and dear to her laid out for a new audience. She wrote on Facebook recently, “I hope it sets people’s hearts on fire for the ERA.”

ALICE PAUL & THE ERA

Nicholson’s heart lights on fire when she starts talking about the “Mother of the Equal Rights Amendment,” Alice Paul. She has become a scholar of the suffragette and ERA author and loves to tell her stories. Referring to Paul as her “north star,” Nicholson penned (and stars in) the one-woman play Tea with Alice and Me: The Intersecting Lives Of Two Feminist Elders, which explores their similar trajectories as political activists inspired by their spiritual convictions for equality.

Paul often ruffled the patriarchal establishment’s feathers and sometimes even faced angry mobs in response to her direct action tactics. In a March 2021 op-ed, Nicholson wrote, “Did you know that before March 3, 1913 no one had marched to the White House? Not a protest, not a demonstration, not a parade. Miss Paul was the first. She was the first to bring nonviolent direct action to the United States. Long Beach activists can learn much from Miss Paul.”

After groundbreaking efforts by feminists, the 19th amendment passed in 1920, giving women the right to vote. But Paul was not ready to stop there.

“Women will not be safe until the principle of equal rights is written into the framework of our government,” she said presciently at the time, which is why Nicholson says Paul knew getting the vote wasn’t enough.

Nicholson says Paul had this epiphany back in 1906 while working in a settlement house on Rivington Street in New York City. While assisting new immigrants with acclimating to their new environment, it occurred to Paul that social services were not enough to ensure equal rights. Having the right to vote would not secure equal treatment under the law either. Paul knew constitutionally protected rights were a necessity for true equality, and was willing to fight for it.

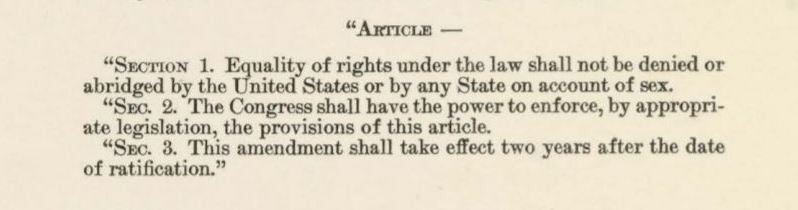

After earning three law degrees, Paul drafted the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923 and presented it to Congress that same year. Sadly, the ERA did not pass in 1923 and has continued to be presented to every Congress since.

WHY IS THERE PUSHBACK ANYWAY?

Paul’s three-sentence amendment, seemingly innocuous, has received a vitriolic backlash from the anti-ERA crowd since the day it was introduced up until present day. There were accusations of it breaking traditional gender roles by sending women into combat and encouraging homosexuality. Phyllis Schlafly’s anti-ERA group was named Stop Taking Our Privileges (STOP) because they claimed it would result in the elimination of child support for divorced women and social security for widows. Abortion and fear of gender neutral bathrooms continue to be the main issues decried by anti-ERA politicians and conservative pundits.

Nicholson says, “They are looking for any possible reason to cover up the real reason… [which] is because women make up the cheapest workforce on the face of the earth. If they actually had to pay not only equal wages but equal pension, equal social security, equal 401(k)s, equal bathroom space, equality under the law on all scores, it would cost the patriarchy a fortune because they have been running on the fuel of the oppressed since they began.”

Eleanor Smeal, president and co-founder of the Feminist Majority Foundation and former president of the National Organization of Women (NOW), testified at a Congressional hearing in October 2021: “The biggest opposition to the ERA came from the Chambers of Commerce, National Association of Manufacturers, and the insurance companies—they were big lobbyists against us.” Many insurance policies were discriminatory based on sex and gender and to treat men and women equally would hurt their pockets.

THE SECOND WAVE

In August 1970, the ERA gained mainstream momentum riding what was called the “second wave” of feminism (the suffragettes’ push for passage of the 19th amendment, women’s right to vote, is considered the first wave). In her first year in office, Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, gave an impassioned speech addressing the opposition and explaining the ERA’s relevance, saying in part:

“The argument that this amendment will not solve the problem of sex discrimination is not relevant. If the argument were used against a civil rights bill, as it has been used in the past, the prejudice that lies behind it would be embarrassing. Of course laws will not eliminate prejudice from the hearts of human beings. But that is no reason to allow prejudice to continue to be enshrined in our laws — to perpetuate injustice through inaction…

The time is clearly now to put this House on record for the fullest expression of that equality of opportunity which our founding fathers professed. They professed it, but they did not assure it to their daughters, as they tried to do for their sons.”

In October 1971, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the ERA. The following year, the Senate passed it as well but a stipulation was tacked on—38 states had to ratify the ERA within a seven-year time limit before it could become the law of the land. This deadline addendum was not required by the Constitution.

In her late 80s at the time, Paul was living across the street from Constitution Hall in Washington D.C. when a group of young feminists ran over to tell her the good news. But when Paul heard about the added condition she said, “It’ll never pass.” Nicholson says Paul knew that all the opposition had to do was stop the 38th state from ratifying it and the amendment would be killed. Paul died in 1977 at the age of 92 without seeing gender equality make it into the Constitution.

As the deadline loomed in 1979, Nicholson recalls that “10,000 women marched [to get the deadline extended] and the response from Congress was, ‘Here ladies, here’s a peanut.’”

That “peanut” was an extension of three years and three months, meaning the clock had been extended through June 30, 1982 to get the final three states to ratify the ERA.

Eight months out from the new deadline, Nicholson, who ran a feminist bookstore in Newport Beach at the time, had a fateful visit from feminist author Sonia Johnson. Johnson, who had recently gained notoriety due to her book, “From Housewife to Heretic,” had been excommunicated from the Mormon church for her support of the ERA. Nicholson and Johnson shared a deep spirituality and a questioning of religious dogmas, which only strengthened their conviction for the ERA. Johnson told Nicholson she would be planning some sort of action since the deadline was looming. Nicholson expressed instantly that to anything Johnson might ask her to do, “the answer is yes.”

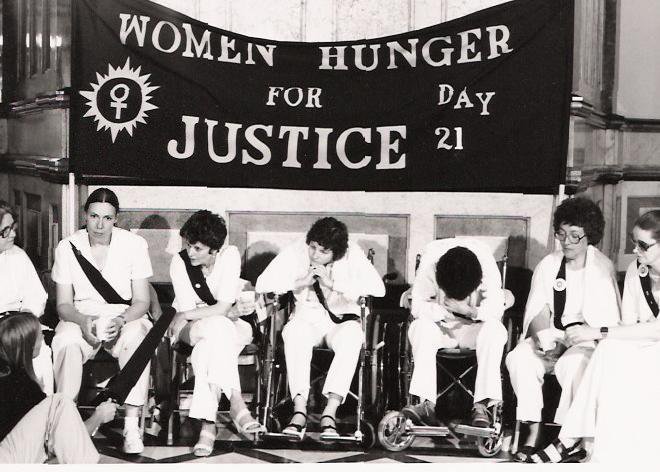

When Johnson followed up later, Nicholson was true to her word. The plan was to go to the rotunda at the Illinois state capitol and to go on a hunger strike “for justice,” with the goal to make a political statement and garner attention for the ERA. With three states needed to fulfill the 38 state requirement, Illinois seemed like a potential win so it became their focus. Nicholson was proud to join a long historical line of spiritual and political fasters, including her beloved Paul who had once led a hunger strike in prison.

Dick Gregory, a master comedian but also a master of fasting, joined them on the seventh day and sat to Nicholson’s right for a week. By this time she was feeling the ill effects of extreme hunger, including irritability, weight loss, and diminishing eyesight (which was especially unnerving because she did not know if her sight would improve) but was determined to continue. She would write in her diary to keep busy but it also served as a shield to keep people walking through the rotunda from bothering her. While Greg (as she calls him in her diary) was there, she also spent a lot of time talking to him and asking him about his knowledge of fasting. He helped them all to understand what typically would happen to their bodies, encouraging them to lean into the spiritual nature of it. In her diary (which was later published in 2004 under the name “The Hungry Heart: A Woman’s Fast for Justice”), she wrote that Greg said fasting “is a pure act and is never used for impure reasons. As he asks ‘Can you imagine anyone fasting for slavery?’”

Recently, Nicholson revealed to YouTuber Joel Marshall that Greg also warned them to only drink spring water. For the rest of their fast, Greg had spring water delivered for them and also provided a doctor for the duration. Nicholson says she was touched that he made sure it was a woman doctor.

But in the end, when the deadline passed, only 35 out of the 38 states needed had ratified the ERA. Nicholson and the other women “hungry for justice” had fasted for 37 grueling days. Thousands of feminists went home feeling dejected, but Nicholson, like her inspiration Paul, has remained forever faithful to the cause.

FEMINISTS SPLINTERED BY ANTI-BLACKNESS & HOMOPHOBIA

Hulu’s limited series Mrs. America had a star-studded debut in March 2020 in the beginning of the pandemic when most of us were quarantining and binge-watching more TV shows and movies than normal. Giving a Hollywood version of the 1982 happenings with Cate Blanchett as anti-ERA crusader Phyllis “Mrs. America” Schlafly and Uzo Aduba as Shirley Chisholm, Nicholson refers to it as that “horrible show” and takes issue with many of its claims. She regrets how many folks will watch it and think they are learning the truth.

Tomisin Oluwole

Dine with Me, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

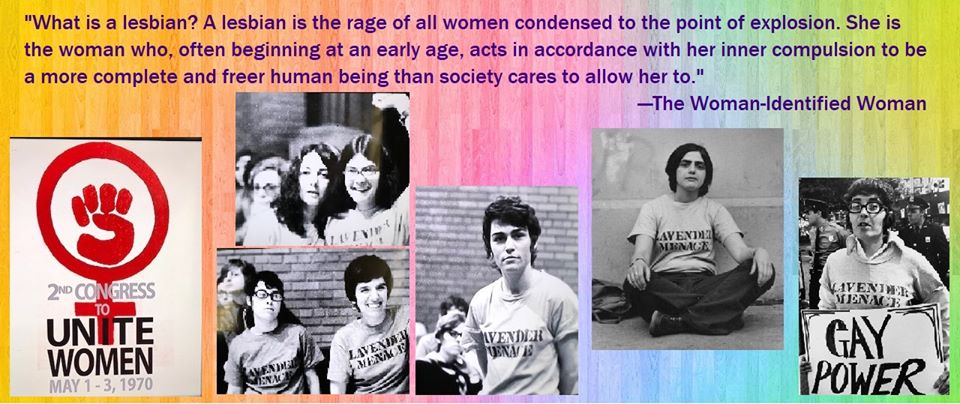

Notably though, there were a couple things she felt it got relatively right. Nicholson, a lesbian and LGBTQ activist, was also glad Mrs. America showed Betty Friedan’s true homophobic colors. Friedan, who was the first President of the National Organization of Women (NOW) and author of the seminal book “Feminine Mystique,” felt that progress was threatened by the visibility of lesbians within the movement. Projecting a fear of being lumped into the man-hating lesbian club, Frieden coined the term “Lavender Menace” at a NOW meeting in 1969. Her homophobia (as well as that of others) was very hurtful and alienating to lesbian feminists like Nicholson.

Another aspect depicted in Mrs. America that was relatively truthful was showing that Chisholm was not fully supported by Black male politicians and was pretty much abandoned by the white feminists leading the charge. Chisholm and many Black feminists dealt with both sexism and racism regularly, and if they were gay, of course homophobia was also lumped on top.

Splintering along racial lines and sexual preferences, the pro-ERA crowd struggled to stay united against its opposers. In the ‘70s, there were numerous feminist groups created to further women’s liberation, some with the explicit intention of freeing themselves from the racism within the Women’s Liberation Movements and the sexism within the Civil Rights movement. Organizations like the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO) with Eleanor Holmes Norton and Margaret Sloane-Hunter centered on developing and implementing Black feminism. The Combahee River Collective, originally the Boston offshoot of the NBFO, with writers like Barbara Smith, sought to raise the consciousness of Black women. A revolutionary group that was anti-capitalist and socialist, the actions of the Combahee River Collective (1974) and many others would impact society greatly for decades to come.

Barbara Smith would later on join a diverse editorial team that included Wilma Mankiller, Gwendolyn Mink, Marysa Navarro, and Gloria Steinum to produce “The Reader’s Companion to U.S. Women’s History” (1998), which helps paint a fuller picture of the history of our nation and the myriad of Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latina women putting in work to actualize the liberation for women regardless of race, class, ability, or immigration status.

Lawyer and activist Pauli Murray is one example (of many) of an integral historical figure who has been marginalized for living in the intersection of Black, non-binary, and gay. (Well before Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” and put a name to why it is important to practice feminism that includes all women.) Murray’s mark on social justice is indelible even if her name is not. A non–exhaustive list of her accomplishments: directly impacted Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, and Ruth Bader Ginsberg, influenced the strategy of the NAACP lawyers working on Brown vs. Board of Education, helped form the National Organization of Women (NOW), coined the term “Jane Crow” to explain Black women’s unique issues, sainted by the Episcopal church. How can it not be due to the triple whammy of racism, sexism, and homophobia/heteronormativity that someone as accomplished as Pauli Murray is omitted from public school history textbooks?

Ayanna Pressley, the first Black Congresswoman from MA who was elected in 2018, reminds us, “We’ve seen this [narrative repeated] throughout history, in an effort to erase the women of color who have served as trailblazers, table shakers and justice seekers in the fight for gender equality.” Pressley also cautions against the “false narrative” of the ERA as a white woman’s issue only.

Contrary to the more conservative arguments, the fight for equity remains relevant and unequal pay still exists. During the pandemic, FORTHE reported on a concerning rise in domestic violence. Statistics show a higher percentage of women without employment (especially women of color) and other serious causes of concern. Many other issues have persisted for quite some time, such as the wage theft of domestic care workers (which are predominantly women of color and/or immigrants), as well as the continued evidence of “misogynoir” (discrimination against Black women) in health care, which we reported on briefly here in 2019.

At a historic hearing held by the House Oversight and Reform Committee to discuss the ERA on the 50th anniversary of it passing Congress, Cori Bush, a newly elected Missouri Congresswoman and Black Lives Matter activist, petitioned the committee to see the disparities experienced by Black and Brown women and “recognize and acknowledge the impact the ERA would have on our communities.” Bush pointed out that Black women are “more likely to be evicted, be underpaid, die during childbirth, lack access to abortion, and be victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and police brutality.”

Bush testified, “It is not surprising that the slave holders, all white men, who wrote the Constitution, did not write in equal rights across genders, and it is not surprising that their disregard for gender equity has disproportionately harmed Black women, Brown women, Indigenous women, and trans women.”

Jennifer Macleod, the national coordinator of the ERA Campaign Network (and someone Nicholson is grateful to “for lighting the way”), wrote in 2020, “American women’s status and opportunities have greatly improved. But this has been the result of them continually and painstakingly working to convince Congress, legislators, and the courts, issue by issue, often state by state, that they should be accorded the equal rights with men that should be their birthright under the Constitution.”

If the ERA is codified into law by being added to the Constitution, all the rest of the piecemeal legislation out there to help combat discrimination based on sex or gender will be strengthened. Until then, as Macleod points out, “Even when anti-discrimination laws are passed, they [unlike Constitutional Amendments] can be weakened, changed, or even overturned by a simple vote of Congress or a state legislature—and often are.”

To explain the lack of efficacy of piecemeal legislation for women’s rights, Nicholson refers to the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act as an example. Notably, former President Barack Obama signed the legislation on his first day in office and commemorated it with dramatic flair.

“There were all these women in red jackets standing around him as he was signing the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act into law. But here’s the problem, here’s what the patriarchy does: The Fair Pay Act says you have to pay men and women the same. But in order for it to add teeth, we needed the associated act, which is the Fair Paycheck Act, which would require employers to make public what they’re paying … and that act has never passed.”

Nicholson continues, “So you might very well work for a company, for Goodyear, and you might believe that the Ledbetter Fair Pay Act is taking care of any disparity of wages. But that would be a false notion, because they are not required by law to make public what they pay. So the end result of that mishap is how the patriarchy always gets us, it’s very interesting to watch. They use the same tricks again and again.”

Looking back, the very idea of adding a deadline requirement was also a strategic tactic to maintain the patriarchal status quo. Nicholson explains that “the patriarchy works in patterns. They attach time limits in particular, obviously to the rights of women, but moreover, to the testing of rape kits, and the statute of limitations on rape. There’s no statute of limitations on murder. There’s no statute of limitations on most things, but if it involves women, oh, there’s limitation. ‘I’m sorry, miss. You cannot press charges. It’s too late.’

‘Oh, you were too upset at the time of the rape to actually report it?

Well, it’s too late now. You’ve waited too long.’”

When Nicholson fasted in 1982, the ERA was up to be the 27th amendment. Nicholson points out, “What became the 27th Amendment is an amendment that guarantees incremental raises for Congress, in their salaries, without them having to ask every time. It just happens as a matter of course…That amendment took 203 years to pass. There was no time limit on that amendment.”

A PREPONDERANCE OF WOMEN

Nicholson stresses that the current resurgence of the ERA is largely due to State Senator Pat Spearman and to the “preponderance of women elected” around the country. Nicholson says Spearman was determined to get more women elected in Nevada and was largely successful.

“If there is any woman who deserves to be lifted in our country right now in regards to equality under the law,” Nicholson said, “I’m going to say her name again for you, it’s State Senator Pat Spearman.”

Elected in 2012, Spearman, who is also a Black woman, a veteran, and has the distinction of being the first openly gay lawmaker in Nevada, is a strong proponent for equal rights. Thanks in large part to her efforts and success at helping women get in office, the ERA was finally ratified by Nevada in 2017. Spearman has now set her sights on becoming mayor of North Las Vegas, throwing her hat in the ring last October.

With inspiration from the momentum in Nevada, the state legislature for Illinois addressed the ERA again in 2018. Current anti-ERA proponents, such as Illinois State Rep. Peter Breen, complained that it was a pro-abortion vote but was outvoted. The state where Nicholson had fasted for 37 days, and faced everything from food taunts to death threats, would become the 37th state to pass the ERA.

In 2020, Nicholson flew to Virginia to witness the (majority women) lawmakers cast the historic vote to make it the 38th and final state needed to ratify the ERA. She watched it from the balcony with the film crew from “Still Working 9 to 5” catching her reaction.

Unfortunately, when the Virginia documents were sent to the National Archivist, they were denied due to a memo from the Trump Administration (specifically Attorney General Bill Barr) to not archive it. The memo pointed to the deadline.

ERA activists are now pushing for the nation to recognize the unconstitutional nature of the deadline. As Nicholson points out, “[The time limit] was an addendum, the reason that’s important is that Congress attached it—which means, Congress put it in there, Congress can take it out.”

A resolution to dissolve the ERA deadline passed the House on March 17, 2021 but remains stalled by, in Nicholson’s words, the “plantation owners in the Senate.” If ratified at this point, it will be the 28th amendment to the Constitution.

NICHOLSON NOW

Back in March 2020, the Women’s Advisory Board and West Hollywood City Council honored Nicholson with a banner on Santa Monica Boulevard for Women’s History Month for her longtime activism. Speaker Mel Lubey, who introduced her, noted that even if or when the ERA is finally officially added to the Constitution, Nicholson will surely not rest because there will still be work to do. After all, as Nicholson continues to say and history has repeatedly shown, “suffrage is unfinished business.”

The current White House administration published a proclamation on Feb. 28 of this year in celebration of March as Women’s History Month saying, “The Congress sent the Equal Rights Amendment to the States for ratification 50 years ago and it is long past time that the principle of women’s equality should be enshrined in our Constitution.”

Activists are calling on the Biden Administration to put their flowery proclamation into real action before the next November election.

The next order of business after getting rid of the barrier of the old deadline and adding the ERA to the Constitution? To make sure it is enforced.

“Still Working 9 to 5” premieres on March 13 at SXSW 2022. To find showings of Zoe Nicholson’s one-woman play, Tea with Alice & Me (The Intersecting Lives Of Two Feminist Elders), or to schedule an ERA 101 presentation, you can find her online hub here. Nicholson’s autobiography “The Engaged Heart: An Activist Life” and her 1982 diary “The Hungry Heart: A Woman’s Fast for Justice” are also available through the same website.

erin@forthe.org

erin@forthe.org