ACLU Says LBPD’s Sharing of License Plate Data Violates State Law

6 minute readThis article is a continuation of our ongoing series The Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach.

The American Civil Liberties Union is accusing the Long Beach Police Department of violating several state laws and risking the civil rights of residents by continuing to share data collected by automatic license plate readers with dozens of out-of-state law enforcement agencies.

The ACLU of Southern California sent a letter on Monday to City Attorney Charles Parkin and Police Chief Robert Luna urging the LBPD to stop sharing license plate data and end its use of ALPR devices.

“The best way to ensure that your residents are safe from unnecessary intrusion into their safety and personal lives is to reject the use of ALPR technology altogether,” the letter reads.

According to the letter, SB 34, a state law that regulates the use of ALPRs by public agencies, prohibits sharing data collected by the devices with out-of-state police departments and federal law enforcement agencies.

An April 6 report from LBPD’s ALPR system shows that dozens of entities, including several divisions of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, continue to have access to LBPD’s license plate data. The report was attached to the ACLU’s letter and obtained by the organization via a public records request.

“This report is the latest in numerous reports which demonstrate that the Department has a long-standing, multi-year practice of sharing ALPR data with out-of-state and federal law enforcement agencies,” the letter says.

The LBPD declined to comment on the matter and directed all questions to the City Attorney’s Office, which did not return a request seeking comment by press time.

ALPRs capture photos of license plates at a rate of up to 3,600 per minute, depending on the model, and also log time, date, and location information. This data can be used to reconstruct historical travel patterns of a vehicle going back years with extreme precision. The software can even predict a vehicle’s location at a particular time.

In 2019, the LBPD scanned over 24 million plates—67,684 per day or a plate every 1.27 seconds, the Beachcomber reported. Of the millions of scans conducted that year, only 0.07% were hits on “hot” cars, according to police records obtained by attorney Greg Buhl who runs local police transparency website CheckLBPD.org. That means that 99.93% of the license plate data collected was on law-abiding drivers.

LBPD’s license plate readers were purchased from surveillance technology vendor Vigilant Solutions. The company encourages indiscriminate data-sharing among the hundreds of agencies on the company’s network with the intent of reaping large profits by selling access to this giant pool of data. In November, the City Council quietly approved a nearly $400,000 purchase of 17 ALPRs from Vigilant Solutions for the Parking Enforcement Division.

In the letter to Long Beach officials, the ACLU said the data “reveals sensitive information about where individuals work, live, associate, worship, and travel. Much of this information has traditionally been unavailable to law enforcement without a search warrant.”

The ACLU warned Long Beach officials in the letter that “ALPR systems are easily misused to harm minority communities—a phenomenon that has been documented for over twenty years. As with other surveillance technologies, police often deploy license plate readers in poor and historically overpoliced areas, regardless of crime rates.”

State Sen. Scott Wiener recently introduced legislation to limit the amount of time law enforcement agencies can retain ALPR data, calling it the “Wild West of mass surveillance.”

Tomisin Oluwole

Coquette

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

A similar letter was sent by the ACLU to officials in Pasadena, where police were also recently discovered to be broadly sharing ALPR data.

“[Pasadena] responded to our letter by dramatically cutting back on the amount of sharing they do, though they did not completely ameliorate the problem. Long Beach seems to be a much more flagrant violator,” said Mohammad Tajsar, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California, who authored of the letters.

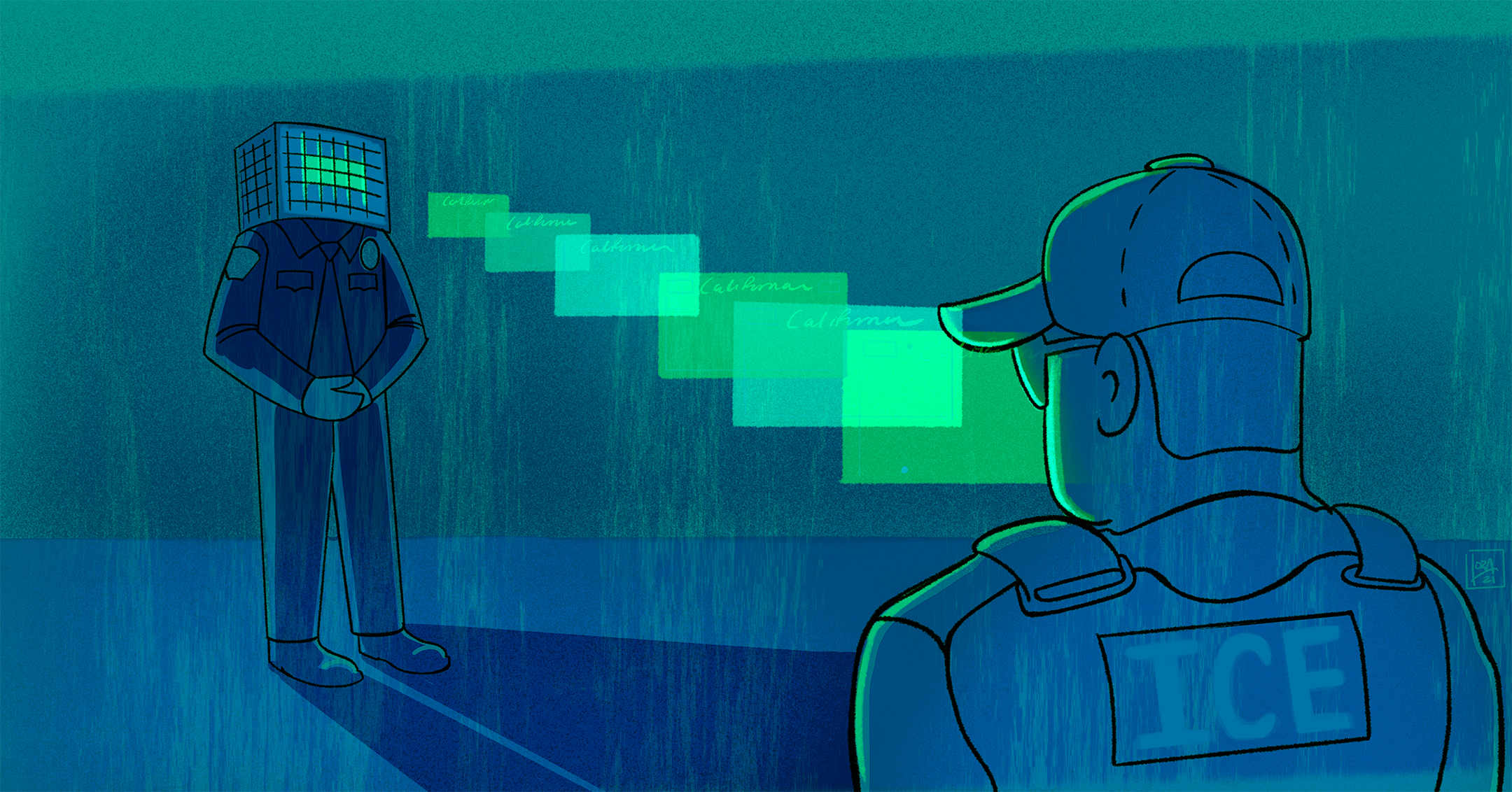

Additionally, the ACLU says the data sharing violates SB 54, more commonly known as the California Values Act, which prohibits state and local law enforcement from sharing immigrants’ personal information with immigration authorities.

“Automated license plate reader data constitutes ‘personal information’ within the meaning of S.B. 54 and the California Information Practices Act,” the letter states. “Given that Long Beach data is shared with U.S. Customs and Border Protection and with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the [Police] Department also violates S.B. 54.”

In December, the LBPD revoked ICE’s direct access to its ALPR database after we reported about it and said ICE had been granted access by error. But experts and privacy advocates we’ve spoken to have said that ICE is likely still able to get its hands on the data due to the vast law enforcement information-sharing networks through which the data flows.

“Shutting off data to ICE doesn’t mean ICE isn’t getting it. ICE just needs to find one willing partner in that chain,” said Brian Hofer, executive director of Secure Justice, a nonprofit that has advocated for better regulation of ALPR technology on the local level.

The ACLU said in their letter that the continued use of ALPRs poses “risks to civil liberties and civil rights” and that even without formal data sharing, the risk of informal data sharing is enough to justify doing away with the devices.

So far, Long Beach lawmakers have remained mum about the revelation that the LBPD shares ALPR data with federal immigration authorities, which breaks promises made by the city’s own Values Act passed in 2018.

Following an ICE raid in Long Beach in July 2019, Mayor Robert Garcia assured residents that police would not share data with federal immigration agencies.

“ICE does not and will not have access to LBPD databases,” Garcia said speaking in Spanish in a video posted to Twitter that month.

The ACLU’s letter accusing Long Beach of violating the California Values Act comes just as the city expects the arrival of a thousand migrant children who will be held at the Convention Center under federal custody as they await reunification with their families.

Local elected officials, including the mayor who himself is an immigrant, have used the occasion to boast about the city’s commitment to supporting immigrants.

The ACLU’s letter says that sharing license plate data with federal immigration enforcement agencies not only violates the plain language of the California Values Act but also “undermines the values” guiding the law, which seeks to foster a relationship of trust between California’s immigrant community and state and local agencies.

The letter asks that the Office of the City Attorney respond to the letter by May 3.

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores