Community Hospital Long Beach to Close in Less Than Two Weeks

14 minute readDespite overtures from the mayor and councilmembers that aimed to strike a deal to keep MemorialCare Community Hospital (CHLB) open while a potential operator change is finalized, the city and the head of the hospital said a months-long closure of the facility will begin July 3.

The announcement comes after preliminary deliberations Thursday during which the facility’s current operator, MemorialCare, agreed to suspend its hospital license at the request of city officials and begin handing off the site to a new company, the hospital’s CEO John Bishop told FORTHE Media.

This development was also confirmed by the city’s Director of Economic Development John Keisler.

“We are happy to report that both the city and MemorialCare staff are meeting collaboratively to discuss a plan for suspending the hospital license and transition the facility to the new operator,” Keisler said.

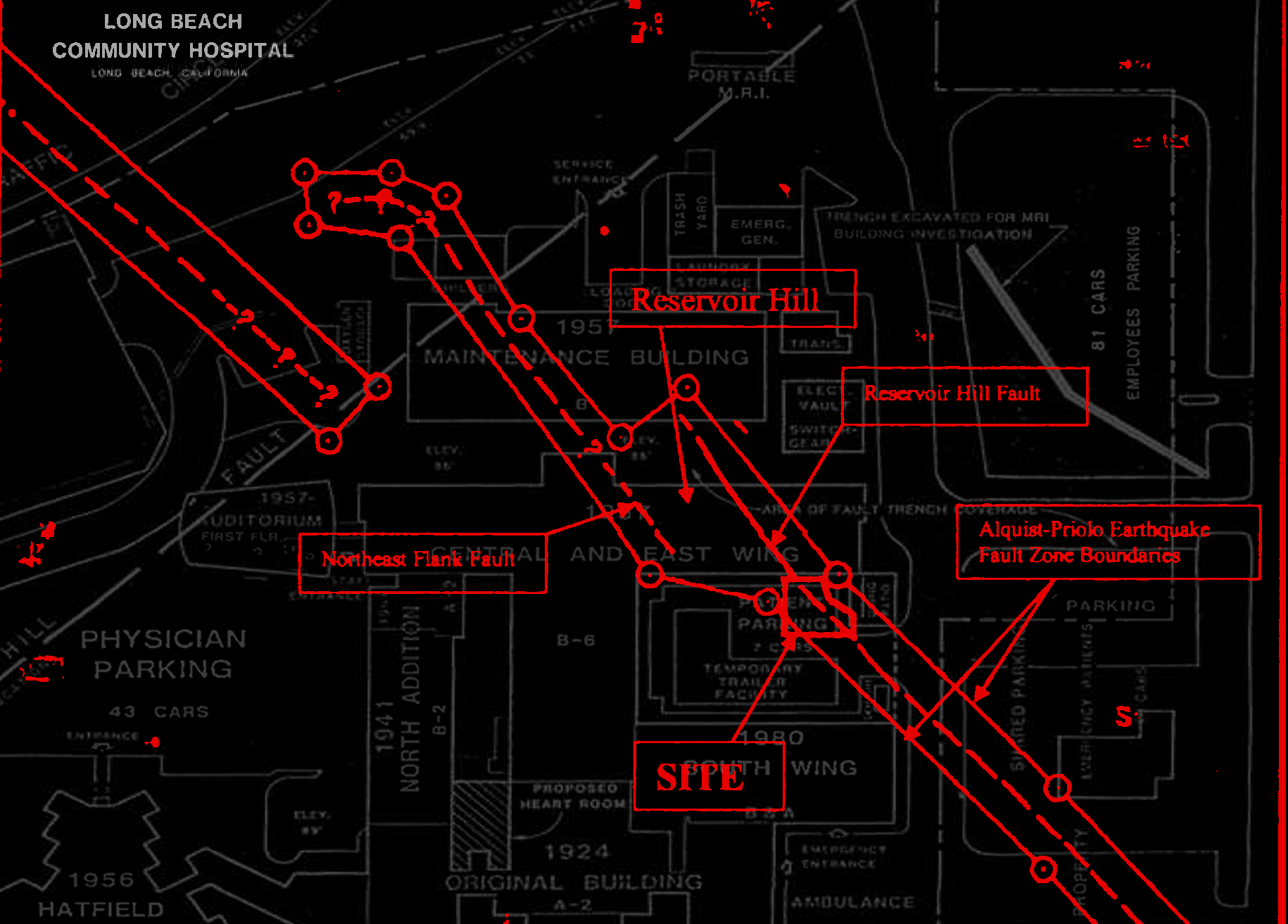

Indications of a possible closure began swirling last year when it was discovered that a fault line running beneath the hospital is larger and more active than previously thought, meaning the site would fall out of seismic compliance next year when new state safety requirements kick in.

Without proper upgrades, state law would require the hospital to cease providing acute care no later than June 30, 2019.

First responders, nurses, and area residents have said that the loss of the 158-bed hospital, even if it’s temporary, would increase patient transportation time, which could have fatal consequences. The hospital houses the only emergency room on the Eastside.

MemorialCare said they decided against retrofitting the facility because it would not result in a large enough hospital to carry out acute care services, and since then the large amount of staff resignations has forced them to set a July 3 closing date. The ER will close earlier, on June 25.

On Tuesday, the Council voted to enter into eleventh-hour exclusive negotiations with a for-profit company composed of Long Beach businessmen Mario and John Molina and two other healthcare executives to take control of the city-owned hospital. They plan to retrofit and reconfigure the site to accommodate an ER.

Even so, Bishop said a six to nine month lapse in service is expected because of a complex web of regulatory hurdles—spanning a myriad of state and federal agencies—that the potential new operators will have to clear before taking over the site.

The regulatory roadblocks were not addressed by electeds or city staff last Tuesday, who had hoped for a smoother transition, but had been publicly reiterated by Bishop for weeks. Because of the regulations, he said it would be impossible to enter into any type of interim management agreement that would keep the hospital’s doors open during the transition.

“We’re at stage zero as far as progress. The management agreement [the city is] proposing is simply impossible to get done in two weeks. The number of regulatory approvals are very significant,” he said.

Hospital employees said that Bishop criticized the city for not being more proactive in avoiding the closure during a staff town hall meeting Thursday.

But efforts to get bureaucratic greenlights have begun, according to CHLB nurse Jackie Mckay. She said a workgroup comprised of hospital and city employees formed weeks ago to tackle some of the requirements involved in the handoff, including a community impact review from the state attorney general’s office.

Changing Hands

The site’s prospective operator, Molina, Wu, Network, LLC (MWN), is comprised of Mario Molina of Golden Shore Medical Group; John Molina, a founding partner at Pacific6; Dr. Jonathan Wu, chairman of Alhambra Hospital Medical Center; and Dr. Kenneth Sim, chairman of Network Medical Management.

Although the company was formed only a week ago, the quartet have over a hundred years of combined experience in the healthcare industry. Within the last year, both Molina brothers resigned from Molina Healthcare’s board of directors. The company reported a $512-million loss for 2017.

Under the staff recommended lease terms between MWN and the city, the 8.7-acre site currently occupied by MemorialCare would be rented to the company for a dollar per year for 40 years. They would then work to create a smaller 40-bed acute-care hospital, a reduction of 118 beds over the current facility.

“We have completed an extensive conceptual design for the consolidation of basic services to support an emergency room in the seismically safe Heritage Building,” Keisler said.

The Heritage building, built in 1924, is the oldest structure on the campus.

During a presentation about the potential MWN lease, Keisler said that with MemorialCare’s cooperation, control of the hospital could be transferred in as little as two weeks, avoiding a disruption of service. Throughout the Council meeting lawmakers cast an unwillingness by MemorialCare to come to the negotiating table as the only obstacle in keeping the hospital open.

“We need and have asked MemorialCare formally to please work with us … to ensure the process continues and that there isn’t a lapse in service. That would be disruptive first and foremost to emergency care,” Mayor Robert Garcia said.

Councilmember Daryl Supernaw (CD-4)—who spearheaded the effort to find a new operator—echoed the public plea to MemorialCare, which also operates the Long Beach Medical Center and Miller Children’s & Women’s Hospital Long Beach.

“Here’s your chance to save face. If you can step up and make this transition now, that would really reinstate faith in MemorialCare doing the right thing for the community,” he said.

We reached out to Supernaw’s office for comment but did not receive a response at press time. We will update this story when we do.

As a solution, the city asked nonprofit MemorialCare to either continue operating the hospital until its current license expires in April 2019, enter into an interim management agreement with the new operator, or suspend its hospital license.

Bishop denied accusations of resisting new operators and said only the latter option given by the city was ever feasible. He explained it would allow a new operator to reinstate MemorialCare’s hospital license under a new name once they’ve jumped through all of the necessary hoops instead of having to reapply from scratch, a costly and time-consuming process.

“We would just be, effectively, the name on the lease and the license and the beds, allowing the city to then work with the [new operators] to see if they can get all their regulatory approvals, seismic approvals, etcetera,” Bishop said.

While the agreement currently in the works gives the new operators a head start by allowing them to be grandfathered into the existing hospital license, it would still require the nearly-century-old facility to temporarily shutter while the government vets the transaction, and Bishop says there’s no way around this.

“It will take six to nine months to do the actual change of ownership, and we can’t keep the hospital open for that long,” Bishop said, pointing to the large amounts of staff that have resigned since the seismic findings were made public, despite bonus offers of up to 20 percent for employees willing to stay onboard.

“Many nurses are the breadwinners in their family, so many people have left because they need a job, they need health insurance, and they can’t wait wondering when this will be resolved,” said Ellen Mockridge, a nurse who’s been at Community Hospital for 35 years.

CHLB nurses said the tumult of the past few months has left many of the remaining employees upset.

“The fact that [Community Hospital] has made money makes us feel like [MemorialCare] can put money into this institution and they should have to. There’s a lot of anger,” Mockridge said.

MemorialCare reported a net revenue of over $200 million last year.

Mckay, who’s been at the hospital for 33 years, said the constant goodbyes to coworkers leaving to work elsewhere throughout the process has had her in a “puddle of tears.” Until recently, the hospital employed some 400 full-time personnel.

“I love this place, it’s my home, I met my husband here, I had my kids here,” she said.

The city’s plan with MWN does include a staff retention component that promises to provide jobs to every impacted employee.

Tomisin Oluwole

Coquette

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

The last time the hospital closed was when a previous operator, Catholic Healthcare West, shut down the facility in 2000. It was reopened after nine months of mounting pressure from the community.

On Shaky Ground

The hospital’s closure has been months (if not epochs) in the making. Last June, MemorialCare notified city officials that a peer-reviewed study it commissioned found that several structures on the campus, including the 30-bed Hatfield building, posed a significant risk of collapsing during an earthquake.

Geologists who conducted the study concluded that the Reservoir Hill fault beneath the hospital was still active. The fault is a segment of the Newport–Inglewood fault system responsible for the devastating 1933 Long Beach earthquake, which ironically enough the hospital—made up of mostly just the Heritage Building back then—survived nearly unscathed.

The discovery means that without a costly retrofit that would require “sawing the [Heritage] Building in half,” according to Bishop, the hospital next year would be in violation of stringent state seismic safety laws governing acute care hospitals. He said the 20-bed facility resulting from the retrofit MemorialCare previously considered would not be capable of offering the level of services it does now.

In a Nov. 13 letter, Bishop told city officials that after consulting with experts, MemorialCare—which acquired CHLB in 2011—determined that they “cannot meet the seismic compliance standards effective June 30, 2019.”

MemorialCare submitted a four-month lease termination notice to the city in March.

The decision caused an outcry from the surrounding community over concerns that the hospital’s loss would create an ER desert on the Eastside. One public commenter during the Council meeting Tuesday said that the proximity of Community Hospital saved her mother’s life after a car crash.

“All over the Eastside, those minutes matter to a lot of people, and if we don’t have that hospital those people are going to die. I’m so grateful that the city is on our side,” she said, adding to the full-throated chorus of speakers supporting the deal with MWN.

Community Hospital’s emergency room treated 27,740 patients last year, and the hospital receives about a fifth of the patients transported by Long Beach Fire Department paramedics.

According to Bishop, the hospital closing would have only a minimal impact on the healthcare services available to Eastsiders. He said that on any given day there are about 800 empty hospital beds in the Greater Long Beach Area.

And while the closure would reduce emergency beds by 6 percent in a 10-mile radius, Bishop said the loss would be blunted by recently completed or planned expansions of emergency services at surrounding hospitals, including at Long Beach Memorial and St. Mary’s Medical Center.

An Acute Care Needs Assessment commissioned by MemorialCare last year found that “three hospitals are located within four miles or less and have sufficient available capacity to absorb the volume from [Community Hospital].”

When asked if patient transportation time would be negatively affected by the hospital’s shuttering, Bishop said: “It would, depending on the traffic, but [Community Hospital] isn’t a primary stroke center, they dont treat acute cardiac patients, they don’t have obstetrical services, they don’t see trauma patients, and they don’t treat kids.”

However, Mckay said that CHLB’s emergency room regularly receives patients with life-threatening injuries who need to be stabilized before they are transferred to bigger facilities.

An impact evaluation from the Los Angeles County Emergency Medical Survives Agency (EMS) also found that “patients with non-life threatening illness or injury will most likely experience longer wait times in the emergency departments of surrounding hospitals.” There are four other acute care facilities within five miles of Community Hospital.

“We get a continuous stream of just simple, ordinary things. People come in with a headache and they only have to sit there for two hours before they figure out if they’ve got a brain tumor or not instead of the 10 hours at the bigger hospitals,” Mckay said.

Another critical service provided by CHLB, the Sexual Assault Response Team, will continue to operate despite what happens with the facility and will be moved to a nearby medical office building, Bishop said.

An earlier bid to convert the site into a non-acute mental healthcare facility by MemorialCare was turned turned down by the city, Bishop said.

CHLB houses 28 of the 144 psychiatric beds within a 10 mile radius. Both the EMS analysis and the third-party community needs assessment found that the area is lacking in mental health services.

But the city has made it clear it is intent on finding a new operator that could retain the emergency room, a position that was reaffirmed by Suzie Price (CD-3) on Tuesday, who recounted recently being rushed to CHLB for emergency spine surgery.

“Every speed bump was felt, every pothole was felt, every stoplight was felt … It was a huge reminder to me of how important it is for us to have an emergency room in the Eastside of Long Beach,” she said.

Verbal Tug-of-War

In what appeared to come across as a big reveal at Tuesday’s Council meeting, Keisler said the city confirmed with the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) that MemorialCare never formally submitted retrofitting plans to the agency, which oversees new infrastructure construction in healthcare facilities.

But that’s a moot point, says Bishop, since retrofitting the existing structures was ruled out by MemorialCare last year, and thus no plans would have been submitted.

Keisler also said that the city was told by OSHPD that the agency never commented on the future of the hospital because it would be against their policies.

But a letter sent last June by Bishop to OSHPD’s Los Angeles Deputy Division Chief Gordon Oakley summarized a meeting the two had previously attended last June: “We all agreed that given all of these circumstances, [Community Hospital] cannot reasonably continue to operate as an acute care hospital in light of current seismic requirements for such facilities.”

In an emailed reply, Oakley said the summary provided by Bishop was accurate.

When asked about this, Keisler provided an evasive answer, saying only that conversations between OSHPD and the city’s contracted architect have so far been “very positive.”

Looking Ahead

If everything goes as planned, the arrangement currently in the works does provide a pathway to getting CHLB’s ER back up and running as early as this winter.

Some challenges still lie ahead though, including a deed restriction on the property requiring that the land be used only for a nonprofit hospital. Under the operation of MWN, the facility would be for-profit.

“The city attorney has indicated that the city council may remove or amend this restriction,” Keisler said.

Another line in the plan that has not been fully fleshed out requests “the city to explore financial participation in the immediate transition and seismic retrofit,” indicating that the city may subsidize some of MWN’s startup costs, despite the cohort’s deep pockets. Keisler estimated that startup costs could be up to $30 million.

Another point of contention might be the millions of dollars currently invested in community benefits by CHLB. They include health education programs and financial assistance for medical bills to low-income patients. Any impact from the potential loss of these benefits would have to be evaluated by the state attorney general as part of the transaction’s review process, and the new operators could be mandated to continue them.

Additionally, the plans being drafted by architect Perkins + Will for the planned CHLB reconfiguration need to be approved by OSHPD, and the Council will still have to vote on any final lease agreement with MWN.

If you appreciate journalism that doesn’t require a conflict of interest disclaimer, please consider supporting local grassroots media by subscribing to FORTHE.

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores