LBPD Facial Recognition Use Saw Major Increases This Year Due to Civil Unrest

20 minute readThis article is a continuation of our ongoing series “The Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach.”

The Long Beach Police Department has used facial recognition technology for investigative purposes at least 3,999 times in the past decade—with over 2,800 of those queries coming between January and September of this year, records show.

Besides accounting for over two-thirds of the overall use, the partial figures from this year represent a roughly four-fold increase in facial recognition queries over last year’s numbers—which totaled 622, according to police records. These numbers do not include the department’s use of commercial facial recognition systems at various periods in the last two years.

The spike is attributed to investigators using the technology to scan faces caught on camera during the May 31 civil unrest in an effort to track down looting suspects, said LBPD spokesperson Arantxa Chavarria. These images could have come from a variety of sources, including closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras and social media.

As of Nov. 23, the LBPD said its Looting Taskforce had arrested 54 people in connection with the May 31 looting. It is unknown how many of those arrests were actually aided by facial recognition technology.

“We do not have statistics for the [facial recognition] usage of the looting taskforce, since they are still in the process of conducting investigations,” said Chavarria.

But the number of looting arrests compared to the increase in facial recognition use raises concerns about how big of a digital dragnet police have cast and the chilling effect it can have on free speech, according to Mohammad Tajsar, a senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California.

“It is disturbing, but not surprising,” he said, noting that law enforcement agencies across the country have been using surveillance technology to track people involved in this year’s civil unrest. “Just the idea that the police department is doing this is enough to make people nervous about participating in the next protest.”

While the department has emphasized that facial recognition technology is only being used to aid in identifying people suspected of criminal behavior, the department’s use of surveillance technology has already roped innocent protesters into criminal investigations.

“There were a whole lot of cameras out there,” Police Chief Robert Luna said at a press conference on June 1, the day after protests broke out around the city in response to the death of George Floyd. “And if you were looting we have your license plate number and we have your face. We’re coming after you and we’re going to arrest you.”

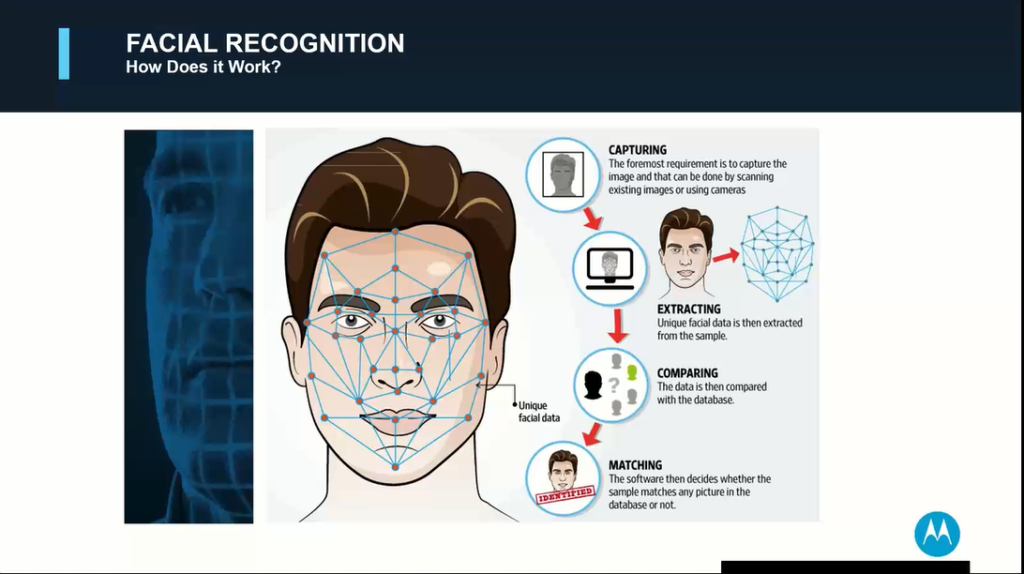

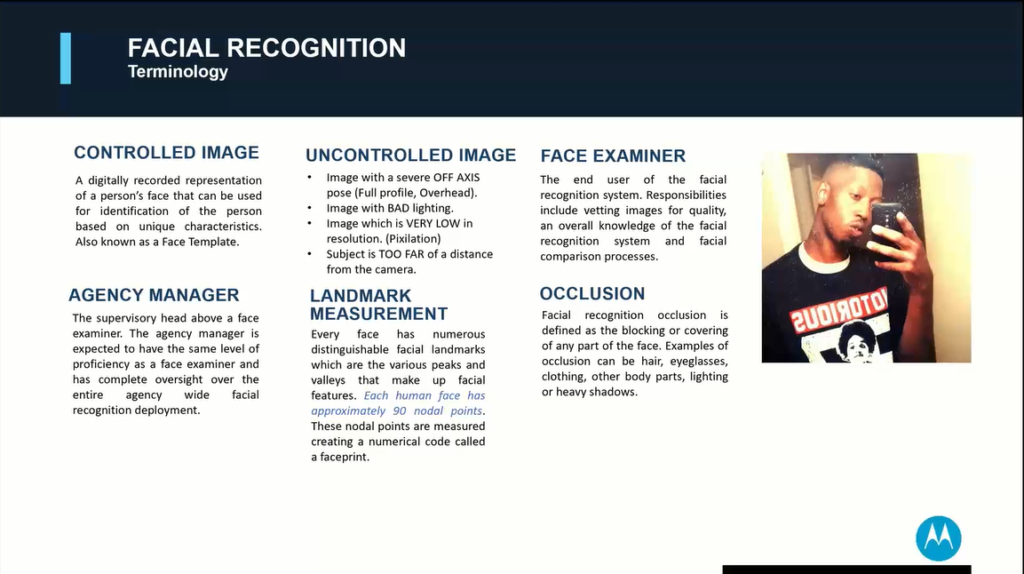

HOW DOES IT WORK?

Facial recognition technology generally works by mapping a photo of a person’s face and measuring certain facial features and variables, such as the length or width of the nose and the curve of a chin, then comparing the measurements against those of photos in a database processed by the same algorithm.

Chavarria says the technology provides investigative leads and that officers are responsible for following up with additional evidence to verify the lead produced by the software before making contact with a suspect.

“Employees are required to evaluate those candidates and establish articulable facts for reasonable suspicion before they make a detention or probable cause before they make an arrest,” she said.

Like all biometric technology, facial recognition software has its limitations. For example, images inputted into these systems have a better chance of producing a useful lead if the photo is of high quality and a person’s face is unobstructed.

While LBPD officers have searched facial recognition systems thousands of times over the years, they have produced relatively few leads.

In response to a public records request by local police transparency website CheckLBPD.org, Long Beach police detectives estimated that facial recognition software had assisted investigations in “approximately 60 cases” through Aug. 16.

STUDIES FIND RACIAL AND GENDER BIASES IN FACIAL RECOGNITION TECH

Studies have shown that facial recognition algorithms can have serious racial and gender biases baked into them.

In 2018, researchers with MIT and Microsoft found that leading facial recognition software had trouble identifying women and people of color, misclassifying Black women nearly 35% of the time. Meanwhile, the study found that white men were nearly always identified correctly.

One of the co-authors of the paper, Joy Buolamwini, said in a TED Talk that these algorithmic biases can lead to law enforcement agencies mislabeling someone as a suspect, especially people of color.

This very scenario played out in Detroit last year when a Black man was wrongfully arrested by police and accused of shoplifting based on a facial recognition mismatch, according to a New York Times report. Robert Julian-Borchak Williams spent 30 hours in custody before making bail.

When detectives showed him the photo they inputted into the facial recognition system, Williams said, “No, this is not me … You think all Black men look alike?”

His case was later dismissed by prosecutors, but he said the ordeal left him feeling humiliated.

A second Black man in Detroit was wrongfully arrested and jailed for three days in 2019 due to a flawed facial recognition match. Michael Oliver is now suing the Detroit Police Department for at least $12 million for botching the case.

A lawsuit has also been recently filed by a Black New Jersey man who says he was falsely arrested and spent 10 days in jail due to a facial recognition mismatch.

The federal government released its own study on the subject last year with similar findings to the MIT and Microsoft study. The majority of the algorithms tested by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology performed more poorly when attempting to identify the faces of women, people of color, the elderly, and children.

Alarming studies such as these have prompted lawmakers in cities across country to pass a raft of regulations on the use of this technology by police.

San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Santa Cruz, Boston, and New Orleans have all banned, limited, or regulated the use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement in the past few years.

Mounting pressure to restrict police from having unfettered access to this technology has also led some big tech firms—including Microsoft, IBM, and Amazon—to announce that they would not sell facial recognition software to police, at least for now. However, the move is considered largely symbolic since those companies aren’t currently big players in the industry. In fact, the leading police surveillance equipment providers are far from household names and tend to keep a low public profile.

Lately though some of those surveillance technology firms have teamed up with police groups to push back against calls to ban the technology from law enforcement use.

“Facial recognition systems have improved rapidly over the past few years, and the best systems perform significantly better than humans. Today facial recognition technology is being used to help identify individuals involved in crimes, find missing children, and combat sex trafficking,” a coalition of 39 technology and law enforcement organizations wrote in a letter to Congress last year.

But companies that hawk this technology to police departments often gloss over the research showing the algorithms perpetuate racism in the criminal justice system, waving off these concerns as sensational.

“My god, the world is going to end because we use facial recognition,” Chris Morgan, a customer success manager for Vigilant Solutions, a controversial surveillance technology vendor, sarcastically told LBPD officers in a recent facial recognition training video.

He goes on to reject various criticisms of facial recognition, including civil rights and privacy issues.

“A lot of the privacy advocates get in a bad way about good people being misidentified by these applications. They’re not good people. These are people who have been arrested and booked. Those are the only people we’re looking at. We’re not looking at DMV photos. We’re not looking at passport photos,” Morgan, a former LBPD lieutenant, said in the training video.

But the idea that only “bad people” are in facial recognition databases used by law enforcement is contradicted by the fact that people who are arrested and have their mugshot taken are not always charged with a crime. One study found that roughly half of all American adults—117 million people—are in law enforcement facial recognition networks.

And researchers say those faces are disproportionately black. A report from the Georgetown Law School Center on Privacy and Technology found that the way police use facial recognition can replicate existing racial biases.

“Due to disproportionately high arrest rates, systems that rely on mug shot databases likely include a disproportionate number of African-Americans,” the report stated.

This means that even if accuracy is perfected, this technology could replicate and possibly accelerate patterns of racial profiling that exist in policing today.

Tomisin Oluwole

Dine with Me, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

“It’s a racist data set. Precisely because it’s a data set of people who are arrested, it’s primarily people of color, because that’s who gets arrested,” said Tajsar. “And that’s to say nothing of the inaccuracy baked into the algorithms.”

POWERFUL TECHNOLOGY REQUIRES POWERFUL POLICY

In the Vigilant Solutions training video, recorded in September, Morgan mentions that the LBPD does not have a facial recognition policy.

“The other thing you have to have is a policy. You gotta have a policy because if you don’t have a policy, the privacy advocates are going to lose their minds and are going to say you’re doing whatever it is you want to do,” Morgan told LBPD officers. “I know Long Beach is working on it but you don’t have one right now.”

Not having a robust policy governing the use of the technology has added to the concerns about the LBPD’s use of facial recognition software.

Currently, the only system authorized to be used by LBPD for investigative purposes is the Los Angeles County Regional Identification System (LACRIS), which compares input photos with a database of criminal booking photos. It is maintained by the LA County Sheriff’s Department.

While LACRIS maintains a bare-bones, six-page policy on its website that touches on officer training requirements and audits of user actions, among other things, it also states that “agencies are encouraged to implement their own policy which complements and does not contradict the LACRIS policy.”

A policy template is even provided for local law enforcement agencies to adopt. Yet, the LBPD, in its 10 years using the technology, has not drafted a more comprehensive policy to govern the use of this technology. As of press time, the LBPD does not have any policies or special orders related to facial recognition on its website.

When asked why, Chavarria dodged the question, saying,“The Department has always required employees to follow state law and LACRIS policy concerning the accessing of Criminal Offender Record Information.”

California has only one law on the books that directly addresses law enforcement use of facial recognition technology. AB 1215 was signed into law last year and temporarily bans using police body cameras in tandem with facial recognition systems.

Chavarria says the department has safeguards to ensure only authorized users access facial recognition systems. She said that officers must be trained before being granted a login key to access the software.

While LACRIS—the sheriff run system—does require each user to be trained by the sheriff’s department, two commercial systems put into temporary use at various periods in the last couple of years by the LBPD appear to have been deployed with little training or guidance for officers, according to police records. Both platforms were in use around the time of the May 31 uprising.

The department made use of a free trial of Vigilant Solutions’ FaceSearch between April 2018 and September 2020, records show. According to the company’s website, its facial recognition app allows officers to share data with law enforcement agencies across the nation. Last month, we first reported that LBPD was sharing license plate data with Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials through Vigilant’s network, a violation of local and state sanctuary laws. The department later said in a statement that a contractor accidentally authorized the data sharing.

The only evidence that officers received any training with the app was the training video conducted by Morgan, which was produced over two years after the LBPD first acquired FaceSearch.

The other third-party platform being used by LBPD officers was Clearview AI. Though the department could not provide a timeframe for its use of this software, emails between officers and the company show that the earliest account was opened in July 2019, with at least 18 accounts being registered before the free trial ended in February.

Clearview AI inhabits something of an ethical gray area due to the invasive database they have created. The company has data-scraped 3 billion images from public social media posts, regular media, personal blog pages, and sites like meetup.com—sometimes in violation of those site’s terms of service.

Under the California Consumer Privacy Act, Clearview AI must provide residents of the state access to data it has collected on them, and the option to permanently delete it from their database. Out of curiosity, I submitted a request to see what images the company had on me and, unsurprisingly, my two latest Facebook profile images were included. What was unexpected was a screenshot of my face from an obscure video I recorded for the Daily 49er as a student journalist in 2015. The video has 68 views. Also included was my Venmo profile picture (?). To find out if your face is in Clearview’s database and to request your data be deleted visit www.clearview.ai/privacy/requests.

While the department acquired the two commercial facial recognition apps under the pretense of testing their capabilities, some evidence suggests officers may have been using them for investigatory purposes.

FaceSeach was used by the LBPD 290 times between April 2018 and September 2020, with 102 of those searches coming after May 31, tracking with the use patterns of the LACRIS system, according to police data. The LBPD did not provide use records for the Clearview AI system and said that the metric is “not available and is not tracked” in response to a PRA request.

In one February email, Detective Jesse Macias writes about having success with Clearview AI, stating, “I personally like it and have heard of others having success…..”

But as the LBPD’s use of facial recognition began to come under scrutiny this fall, with a flurry of PRA requests being made by CheckLBPD.org, the department reined in its unregulated use of the commercial platforms.

On Sept. 29, a watch report issued by Deputy Chief Erik Herzog set restrictions on who could authorize the acquisition and use of commercial facial recognition software for investigative purposes.

“To have a better understanding and to ensure we are maintaining records as required by law, effective immediately any employee initiating a trial of new software they intend to utilize to assist with an investigation must first obtain the permission of their division commander,” Herzog wrote in the watch report, which is essentially an internal memo from police brass to the rank-and-file.

The watch report goes on to state that the department was using the free trials of commercial facial recognition software to research “best practices related to policy and procedure” and that “prior to adopting any new technology, we must have clear guidelines and policies in place to govern the use. Otherwise, we risk losing access to the technology.”

The watch report came about after a flurry of public records requests were submitted by CheckLBPD.org that began to reveal the contours of the department’s facial recognition program.

While Herzog does not explicitly state in the watch report whether the technology had been used for unauthorized purposes, Tajsar of the ACLU said in an email that the document “suggests that members of the LBPD have been inappropriately using trial evaluations of facial recognition products to conduct searches of individuals in ongoing investigations, and not properly documenting the searches in internal records.”

Chavarria said the police department is not aware of any misuse of its facial recognition systems, but did not elaborate further.

“What we can safely assume is that the watch report is necessary to prevent future violations of these reporting requirements,” said Tajsar. “Whether such violations can result in any kind of exposure for the Department, or can materially alter ongoing or past criminal prosecutions, is unclear.”

Last month, the Los Angeles Police Department went even further than the LBPD watch report and barred its employees from using commercial facial recognition software for any purposes after it discovered some officers had used the Clearview AI system without permission.

Because the commercial systems were free trials, their acquisition did not need to be approved by the city manager or the City Council. Likewise, the department is provided access to LACRIS via the sheriff’s department free of cost. This allows law enforcement agencies to keep their use of this technology out of the public’s view.

Historically, the LBPD has been tight-lipped about its use of facial recognition software. In 2017, the department admitted to using the technology in response to a records request by a MuckRock journalist, but also claimed to have no responsive documents regarding contacts, policy, or training.

Then in 2019, the department denied having any records in response to two separate requests for documents related to facial recognition technology, including policies and vendor contracts. The first request was from the Aaron Swartz Day Police Surveillance Project and the second from Freddy Martinez, director of the Lucy Parsons Lab.

Both of these groups study police technology issues nationwide and routinely submit records requests to departments across the nation to track the spread of police surveillance technology.

Even large departments such as the LAPD managed to keep their use of facial recognition under the public’s radar for over a decade. Earlier this year, the L.A. Times reported for the first time that the LAPD used LACRIS 30,000 times since 2009. The Times also noted that the LAPD had stonewalled previous attempts to obtain that information.

In response to the report, the Los Angeles Police Commission vowed to review the LAPD’s use of the technology.

While the Long Beach City Council has not yet publicly approached this subject, the city said in its initial Framework for Reconciliation report that reviewing the LBPD’s use of facial recognition technology is a “medium term” goal, meaning within one to two years.

The report said city officials will “explore the practice of facial recognition technology and other predictive policing models and their disproportionate impacts on Black people and people of color by reviewing evidence-based practices.”

In September, newly elected Sixth District Councilmember Suely Saro said she was deeply concerned about law enforcement’s uses and potential abuses of facial recognition technology.

“Our default position on these technologies should be that they should not be used,” she said. “Any changes to that policy should have to be carefully scrutinized and evaluated through an open and public process.”

Additional research and reporting by Greg Buhl, an attorney who runs CheckLBPD.org. All of the public records used for this article were obtained by Buhl.

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores