Trove of LBPD Records Destroyed Weeks Before New State Transparency Law Takes Effect

8 minute readThe Long Beach Police Department said a year-end destruction of decades worth of internal investigation records was not influenced by an impending state law that would have opened them up to the public for the first time when it goes into effect on Jan. 1. Instead they said the decision stemmed from recommendations made by a consultant that were meant to tighten up the department’s recording-keeping guidelines and free up space.

The purge of a 23-year backlog of internal affairs records, ranging from 1978 to 2001, comes on the heels of a Los Angeles Times report that the Inglewood Police Department also planned to destroy police records weeks before the new transparency law kicks in.

“I get with the other stories that are coming out, [some might ask] ‘Is it related to [Senate Bill] 1421 or not?’ and it’s not,” said LBPD Cmdr. Erik Herzog.

SB 1421 will require law enforcement agencies to divulge some records related to internal investigations of officer shootings, other major uses of force, confirmed cases of sexual assault, and lying while on duty.

Dawn Modkins, a co-founder and organizer for Black Lives Matter, Long Beach, said the timing of the destruction raises suspicion, especially considering how long the records were kept past what was required by state law.

“It’s pretty ironic that literally two weeks before [Senate Bill 1421] goes into effect [the LBPD] decides to make an unprecedented request to discard 23 years of documentation regarding complaints against them,” said Modkins. “Our history is being erased again.”

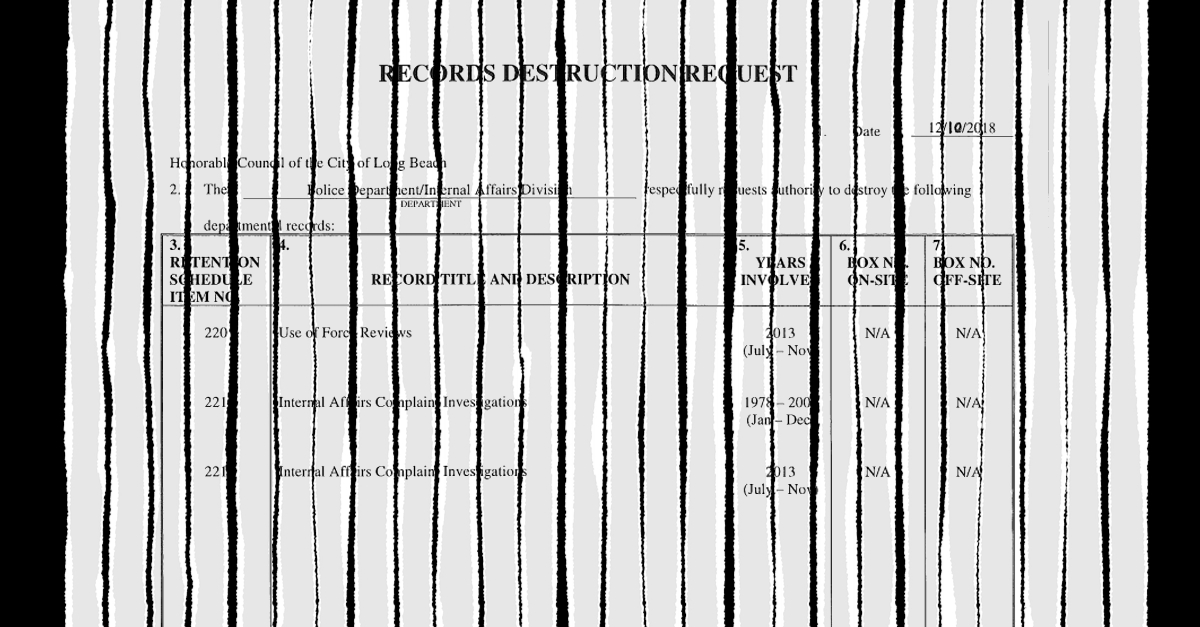

The Long Beach City Council authorized the destruction of the records on Dec. 18 during their final meeting of the year.

While the records destruction in both Long Beach and Inglewood complied with the five-year retention period required by the California Public Records Act for these types of records, civil rights and criminal justice reform advocates said the record dumps violated the spirit of SB 1421.

But unlike in Inglewood’s case, Herzog stated that records from the LBPD’s purge did not include any material related to officer shootings or in-custody death investigations. However, Herzog said the records “likely” contained cases related to lesser use-of-force complaints and may have also contained records related to probes of other types of serious police misconduct.

“The other part of [SB] 1421 is sexual assaults and untruthfulness. The way we track cases I don’t know if there were any in there. Those things are extremely rare so I guarantee you the vast majority of them had nothing to do with that at all,” Herzog said.

Exactly what types of cases were among the records destroyed is unknown because the department did not keep a tally.

Herzog confirmed that the records have already been destroyed and said they did not involve current employees. Though it’s unclear if any of the investigatory files pertained to personnel who have moved on to other police departments.

“The records we recently destroyed would not of come up in any criminal or civil cases in recent times as they were so old there are no legal matters involving them,” Herzog said.

Modkins said that while the records were old, they would have still presented some value to the public.

“Those 23 years are just as relevant as yesterday. It enables the public to see patterns, to see where there are improvements, to see where departments have gotten worse. It removes also the possibility for police to show improvement. There’s no record now. It takes away measurability to their abuse,” she said.

A week prior to approving the records destruction request, the City Council approved numerous changes to the Long Beach Police Department’s records retention schedule. Among those changes, the amount of time the department has to hold on to records related to sustained complaints of police misconduct was shortened from indefinitely to five years after a case is closed. This rule change—which is still in alignment with state law—opened the door for the decades-old records to be shredded last week.

The LBPD said those changes were part of a citywide effort to update various department’s record-keeping guidelines and were recommended by a records management consultant in 2017.

“We started on this a long time ago and [SB] 1421 happened to come up,” Herzog said. “The timing, we get it, but hey we can’t stop business. No matter what, people are going to ask that question.”

Responding to the Inglewood case, the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, told the LA Times that the destruction of records “undermines police accountability and transparency against the will of Californians.”

Among the organizations endorsing SB 1421 were the ACLU of Southern California, California chapters of Black Lives Matter, and the Long Beach chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice. Opposing it were various police officer unions, the California Police Chiefs Association, an the Association of Deputy District Attorneys.

Tomisin Oluwole

Fragmented Reflection I, 2021

Acrylic on canvas panel

24 x 30 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Protests against the records destruction were held outside the Inglewood city hall last week, while the city’s mayor James T. Butts defended the purge as “routine.”

The LBPD records destroyed covered a span of time when the department was plagued with allegations of bigoted behavior and police abuse against members of the LGBTQ community and minorities.

In 1986, 56 lawsuits were lodged against the department and in 1989, 746 complaints were filed against its officers.

One prominent case from 1989, involved a traffic stop that led to Ron Jackson, a former Hawthorne police officer, being smashed through a plate glass window by an LBPD officer during a traffic stop. The encounter was videotaped by an NBC camera crew as part of a sting operation to show the department’s abuse of minorities.

The incident was nationally televised and eventually led to voter support for and the formation of a Citizen’s Police Complaint Commission.

“Over the years, Long Beach’s 644-member police force has been subject to the same kinds of allegations of mistreating minorities that are being leveled at the Los Angeles department,” wrote the LA Times in 1991, months after the Rodney King police beating.

The staff report accompanying the LBPD destruction request did not mention SB 1421 nor did it enumerate what cases were among those marked for destruction, as was done in Inglewood. Instead the records were labeled as “Internal Affairs Complaint Investigations.”

An email to the city attorney’s office asking if they notified the police department of the incoming state law before deciding to destroy the records was not returned by press time.

Records destruction requests for all city departments are typically placed on a portion of the City Council’s meeting agenda called the consent calendar by the city clerk. The consent calendar ostensibly serves as a place for items deemed routine and non-controversial and therefore don’t get public discussion before being voted on unless the mayor, a council member, or city manager requests it be discussed.

All nine members of the City Council signed off on the Dec. 18 consent calendar, which included the LBPD’s records destruction request.

For years the police department has generally gotten rid of internal investigation records twice a year in six-month batches as they become eligible for the circular file. However, in terms of the time encompassed, this is the most far-reaching destruction request for LBPD internal investigation records in at least eight years, a review of those requests shows.

“Historically, [the department] has not been good at cleaning stuff out,” said Herzog, who noted that the records in question were never digitized.

Modkins said the destruction was part of a larger pattern by the department of whitewashing police abuses against marginalized communities.

“How are you going to establish equity, with no history of inequity?” said Modkins. “It’s intentionally destroying the opportunity to create equity. It’s intentionally destroying the opportunity to make space for justice.”

Earlier this year the LBPD was accused of breaching the state’s records retention laws after it was revealed that some of its personnel were using the self-deleting messaging app TigerText (rebranded TigerConnect) on their department-issued cell phones.

However, a review commissioned by the city and completed earlier this month concluded that there was “no evidence to support claims of illegal use or misuse of the TigerConnect app by the PD.”

While SB 1421’s author, Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley), said it’s provisions should apply retroactively to all qualifying records kept by law enforcement agencies, The San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Employees’ Benefit Association has asked the California Supreme Court to limit the legislation’s breadth to cases that are opened after the bill has taken effect. The court’s decision is still pending.

Notwithstanding the union’s injunction request, at least some of the records destroyed by the LBPD last week would have become open to the public for the first time on Jan. 1.

If you want to see more local journalism that doesn’t require a conflict of interest disclaimer and isn’t owned by corporate interests, please consider supporting grassroots media by subscribing to FORTHE.

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores