City Council to Decide Whether to Buy Controversial License Plate Readers

14 minute read11/21/20: The Long Beach Police Department has removed U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement from a list that appears to show agencies that have access to the data collected by the department’s license plate readers. You can view the document here.

11/17/20: The City Council approved the purchase of the license plate reader devices.

The council voted to spend $400,000 on the license plate readers despite a member of the public saying, “I’m questioning why the city is using funds for this specific issues especially at a time when the city is asking to stop the over-policing of brown and Black bodies.” https://t.co/KQ1jNBPAEZ pic.twitter.com/ioSAMakZpG

— LBC Meeting Notes (@LBCMtgNotes) November 18, 2020

This article is a continuation of our ongoing series The Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach.

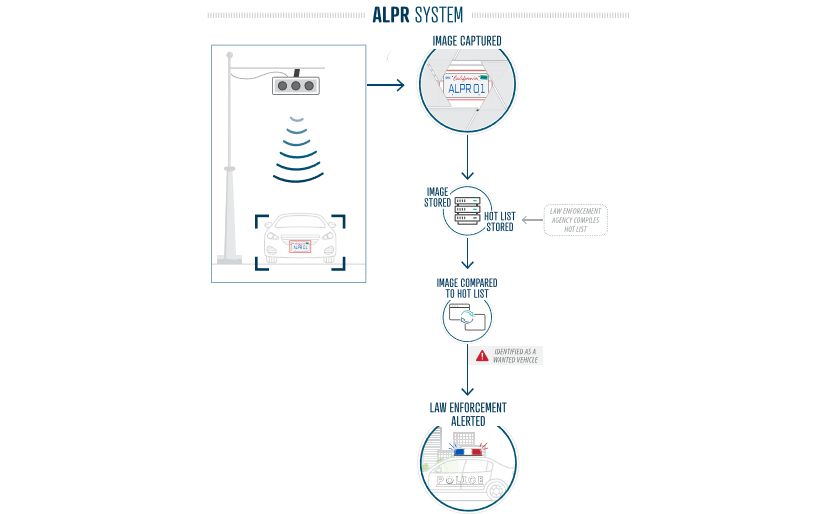

Inconspicuously placed on the consent calendar of today’s mammoth City Council agenda is an item recommending the purchase of 17 automatic license plate recognition (ALPR) devices with a price tag of nearly $400,000 for the Parking Enforcement Division.

The software and hardware the city is looking to buy comes from Northern California-based Vigilant Solutions, a law enforcement contractor and a subsidiary of Motorola Solutions. Over the years, the Long Beach Police Department has purchased dozens of ALPRs from Vigilant. The company also sells access to a vast databases filled with the billions of license plate records collected by these devices.

One agency with access to these records is U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). An internal report from the LBPD, obtained via a public records request, lists ICE as one of over a thousand agencies with which the police department shares data collected by its license plate readers.

When contacted, the LBPD said they were unsure why ICE shows up on that list, claiming that the department does not share ALPR data with immigration authorities in line with the department’s policy prohibiting officers from assisting in the enforcement of federal immigration law.

The city’s staff report to the council, which recommends the purchase of the ALPR devices, does not mention any of the potential privacy and civil liberties concerns presented by the technology. Instead it’s cast as a routine acquisition.

“The Vigilant ALPR system will replace an out-of-date ALPR system currently installed on three of the Parking Enforcement vehicles and the system will be installed for the first time on the remaining 14 vehicles,” the staff report states.

According to the company’s website, Vigilant’s cameras are capable of capturing 1,800 license plate numbers per minute and can be mounted on vehicles or traffic signal poles.

The police department made its first purchase of ALPR devices in 2005, billed as a cost-effective tool for increasing citation revenue and finding stolen cars. In 2011, the city spent $900,000 to buy over 40 ALPR devices.

Former Long Beach police Lt. Chris Morgan—who has since become a Customer Success Manager with Vigilant Solutions—implemented and led the expansion of Long Beach’s ALPR system. In a 2008 interview, he said that despite the success police had with impounding vehicles with outstanding tickets, “the biggest benefit” of the technology was “data mining,” which he claimed allowed investigators to solve numerous felonies at the time.

Since 2014, the LBPD has paid Vigilant Solution $24,999 a year to use its software and LEARN database, according to vendor invoices turned over by the department.

More recently, LBPD’s data mining of license plate records has led to innocent people getting roped into criminal investigations. Earlier this year it was reported by the Beachcomber that the LBPD attempted to use license plate numbers collected by ALPR devices during the May 31 anti-police brutality protest to track down suspected looters.

The dragnet led to two women being stopped by police in other jurisdictions and having their vehicles impounded. One was even held at gunpoint by law enforcement officers in Hesperia. Neither woman was charged with a crime, yet both had to “furnish proof of their whereabouts on the day in question” and pay a hefty fine to retrieve their vehicles. The Beachcomber reported that the fines were later refunded but that no apology was issued by the LBPD.

While ALPR data can be a tool for serious police work, it’s most commonly used to ferret out vehicles with unpaid parking tickets or other citations, though the amount of data points it collects dwarfs the number of hits produced.

In 2019, the LBPD scanned over 24 million plates—67,684 per day or a plate every 1.27 seconds, the Beachcomber reported. Of the millions of scans conducted that year, only a fraction of a percent were hits on “hot” cars, according to police records. In Long Beach, it boils down to 0.07%, meaning 99.93% of the data collected is on law-abiding drivers.

CRACKING DOWN ON PARKING TO BALANCE THE BUDGET

According to the City Council staff report, Vigilant’s ALPR devices are being recommended for purchase by the parking enforcement will connect and feed into LBPD’s existing network of ALPRs.

“The need for communication and interaction with the existing Police Department system made Vigilant the only possible provider for the service to ensure compatibility and functionality within the City’s existing systems,” the staff report reads.

Dave Maass, a senior investigator with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights organization, says this expansion of the police’s ALPR network raises serious privacy concerns.

“This means that LBPD will be collecting data on innocent people’s destinations even when they’re not driving on the road,” he said. “It means that LBPD will have a much larger and more detailed database that they can use to track your movements. Imagine if parking enforcement drives around a church or an oncology clinic: they will have ultimately collected data about your private activities that are neither criminal or anyone’s business.”

The City Manager’s Office did not reply by press time to a set of questions sent Monday morning about the potential purchase and criticism of the technology.

Vigilant’s ALPR system is capable of capturing geolocation data saved by time, date, and license plate number, meaning a plate can be recorded multiple times in a day with location coordinates tracking a vehicle’s movement. When license plate numbers are linked with the state’s Department of Motor Vehicle database, drivers can be personally identified.

An ALPR system as extensive as Long Beach’s collects enough information that it can be used to determine where someone lives, works, goes to school, banks, or receives medical treatment.

California was one of the first states to recognize the potential for abuse of the technology and in 2015 passed Senate Bill 34 to create standards for ALPR access, use, data sharing, data protections, and audit responsibility.

Examples of database misuse by officers in other cities has been found to include use of ALPR systems to stalk women, blackmail closeted gay bar patrons, track movements of spouses and children, spy on celebrities, search friends and dating partners, conduct searches related to private business deals, and selling access to the system.

A 2019 report by the California Auditor, a nonpartisan government agency, found all four of the California law enforcement agencies audited were out of compliance with SB 34 four years after its passage, including the Los Angeles Police Department.

While the state auditor did not analyze LBPD’s policy, looking at the LBPD’s ALPR policy posted online makes it apparent that department is out of compliance with state law as well.

For instance, the LBPD’s policy does not disclose how ALPR data is stored and what data security measures it has in place to protect it, which, according to the state auditor, are requirements of SB 34.

The city’s staff report recommending the purchase of ALPR equipment did not address whether parking enforcement has its own SB 34-compliant policy for license plate readers.

The requirements of SB 34 apply to other institutions as well. For example, Cal State Long Beach uses ALPR for parking enforcement, but has not posted a SB 34-complaint policy online, as the University of California, Los Angeles and other schools have.

Maass said any jurisdiction using ALPR systems for parking enforcement should have tight regulations on how long the data is stored.

Tomisin Oluwole

Coquette

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

“For one, if you’re using it for parking, then the data should be purged immediately once it’s fulfilled its purpose. I’m talking hours, not days or weeks or years. ‘Parking enforcement’ shouldn’t be an excuse for an immense surveillance operation,” he said.

According to the LBPD’s ALPR policy posted online, the department retains license plate data for two years.

The city says the technology will help parking enforcement personnel do their job more efficiently because it features “automatic chalk technology, high definition cameras, a client portal, payment validation, and the ability to interface with a managed server.”

A major selling point of this technology pushed by Vigilant Solutions’s marketing material is that it can help cities increase the revenue they bring in from parking violations. The price of parking tickets in Long Beach has steadily increased over the years, with the latest $10 bump approved with the city’s 2020 budget.

The corresponding budget proposal stated that the fine increase was a “significant factor in helping to balance the budget.”

SHARING DATA WITH ICE? IS LONG BEACH KEEPING ITS SANCTUARY PROMISE?

Concerns from civil liberties and privacy advocates about this technology go beyond just misuse by local law enforcement agencies and extend to federal agencies that have access to the records fed into Vigilant’s database.

In 2018, it was reported that ICE was accessing Vigilant’s database of billions of license plate records and could use them to track a vehicle’s location in the last five years.

“Knowing the previous locations of a vehicle can help determine the whereabouts of subjects of criminal investigations or priority aliens to facilitate their interdiction and removal,” said a 2015 Department of Homeland Security assessment of the technology.

After ICE had began having trouble accessing Vigilant’s database due to contracting problems, privacy concerns, and accusations that it was targeting non-criminal undocumented immigrants at shopping malls, someone created three accounts for ICE and U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents on LBPD’s system. This continued until July 2017—three months before the California Values Act would have forbidden the practice.

But police records show that as recently as August, the LBPD may have been sharing license plate information with ICE—though it’s unclear how much or for what purposes.

The LBPD listed ICE on an “Agency Data Sharing Report” generated by its Vigilant Solutions system. The internal report was obtained via a public records request by CheckLBPD—a local police transparency website—and reviewed by FORTHE Media.

Asked about the report, the LBPD said it does not share information with ICE.

“Now that this report has been brought to our attention, we have confirmed we are not currently sharing information through the ALPR system. The Department will conduct an administrative review of why they are listed in the August report,” said LBPD spokesperson Arantxa Chavarria in a statement.

The California Values Act only allows law enforcement agencies to provide immigration authorities with information when it relates to a person with a criminal history.

To further clarify the restrictions imposed by the Values Act, the California Department of Justice issued a bulletin in 2018 that provided law enforcement best practices for handling databases in light of the California Values Act. It states that any data-sharing agreements with other law enforcement agencies should include “policies that prohibit the use of non-criminal history information for immigration enforcement purposes.”

The state auditor later said that law enforcement agencies should apply the guidelines in the bulletin to ALPR databases.

But in response to a records request for all data-sharing agreements going back to 2013, the LBPD did not produce an agreement with ICE, meaning if data was being shared between the agencies, there would have been no restrictions in accordance with the California Values Act.

In 2017, when Long Beach passed its own Values Act, becoming a so-called sanctuary city, Mayor Robert Garcia told KPCC that the resolution would “ensure that we are not sharing information that is inappropriate with federal authorities, and that we are really protecting people’s information.”

In addition to ICE, the data-sharing report appears to show that the LBPD shares their ALPR records with over 1,200 other public agencies, including the San Diego Sector Border Patrol.

“Unless a law enforcement agency verifies each entity’s identity and its right to view the ALPR images, the agency cannot know who is actually using them,” the state auditor’s report said.

Maass said that based on LBPD’s internal report, the department is sharing license plate data with a “ridiculous number” of entities.

“There’s no reason small police departments on the East Coast need to access Californians’ travel records and sharing with ICE flies in the face of the California Values Act,” he said.

ITEM PLACED ON THE CONSENT CALENDAR

SB 34—the law that set standards for the use of license plate reader data—also requires cities intent on setting up an ALPR system to give the public a chance to comment on it before implementing the program.

Because Long Beach’s network of licence plate readers was established long before SB 34 went into effect, it’s uncertain if the public will ever get a dedicated hearing on the city’s use of the technology. Other cities, such as Montclair, that had ALPR programs in place before the state passed SB 34, have interpreted the law as requiring a public hearing on their existing ALPR programs in order for them to continue.

Placing the purchase of ALPR equipment in the consent calendar, among 48 other items, certainly violates the spirit of SB 34, especially because it won’t get any council discussion unless flagged by a councilmember.

Will councilmembers give this item the consideration it deserves when it involves the data and privacy of their constituents?

While waiting to find out, individuals concerned about their privacy are empowered by the California Consumer Privacy Act to request, delete, or stop the sale of their personal data.

To do so, follow the instructions here to remove yourself from any database Vigilant Solutions may have added you to.

Additional research by contributor Greg Buhl, an attorney who runs CheckLBPD.

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores