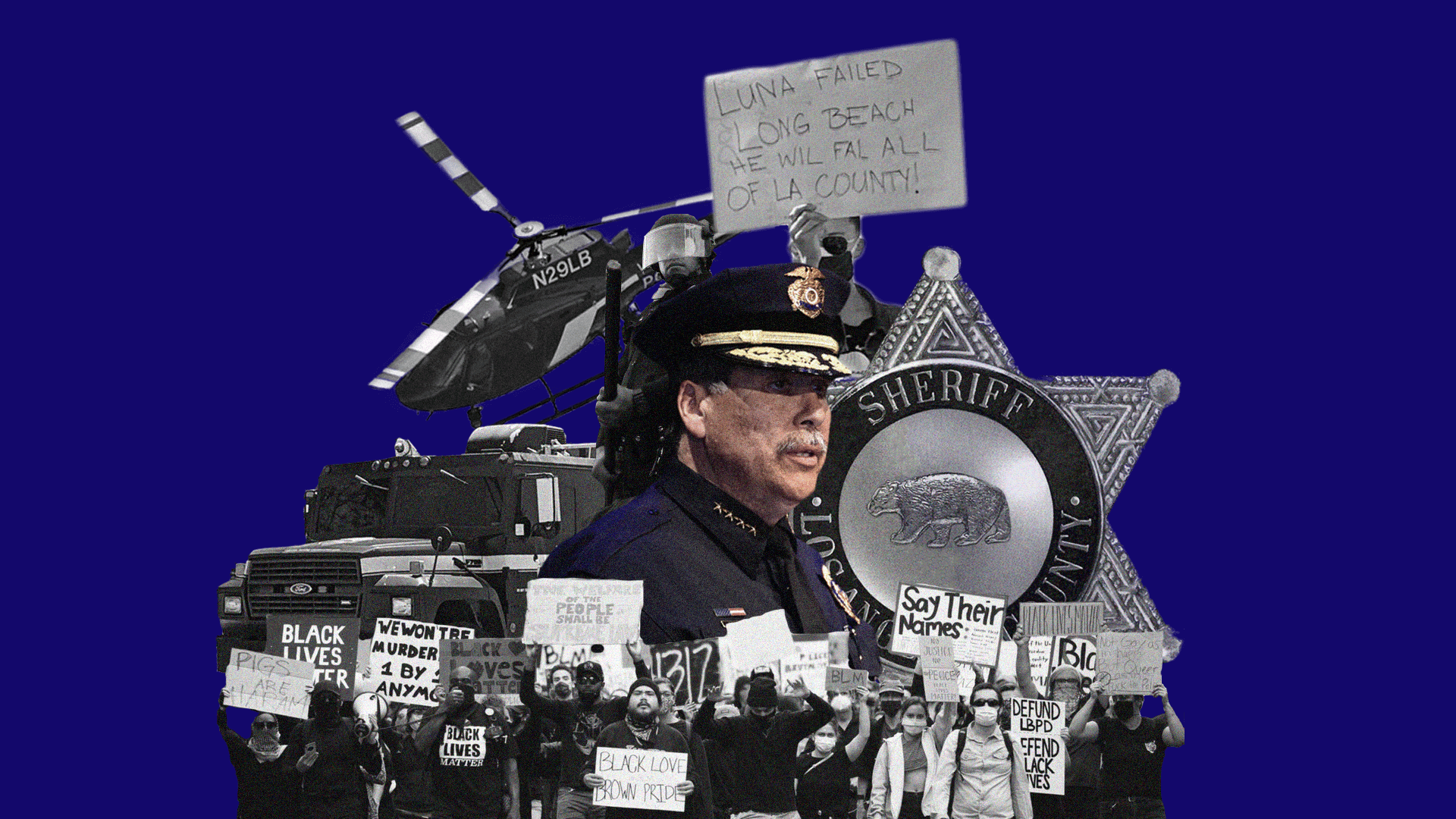

After 7 Years of Cover-Ups, Surveillance, and Costly Police Killings, LBPD Critics Say Chief Luna Unfit to be Sheriff

26 minute readWhen Long Beach Police Department Chief Robert Luna stepped up to a lectern perched atop Signal Hill to announce his candidacy for LA County Sheriff earlier this month, he expected his speech to be accompanied by a panoramic view of the city he’d policed for the last 36 years, seven as chief.

Instead, his announcement was spoiled by members of Black Lives Matter, Long Beach who held up signs warning the rest of the county that he had “failed Long Beach,” later resulting in some very strategically cropped photos shared by the Luna campaign.

“We felt like it needed to be said,” says Audrena Redmond, co-founder of BLM-LB and one of the photobombing protesters. “We don’t think Robert Luna should take his failed policies, failed thinking, and his lack of imagination to the county level.”

Luna, 55, who spent most of his adult life climbing the ranks to the top of the LBPD will be retiring from the department at the end of this year and will be replaced by Assistant Police Chief Wally Heibesh.

Since this publication’s inception, FORTHE has reported on controversies, missteps, and shady practices that have marred the LBPD under Luna’s watch—contrasting significantly with the promises he’s already begun making to voters should he be elected to be the county’s top lawman.

Here’s a rundown of key criticisms of the LBPD under Luna’s watch during the last seven years, including costly excessive force cases, misuse of surveillance technology, and inadequate COVID-19 precautions.

Editors’ Note: FORTHE reached out to the Luna campaign for a response on Monday but a representative declined to comment until Luna retires at the end of the year.

The campaign redirected us to the LBPD Media Relations Detail. After initially agreeing to provide a written response from Luna, the LBPD ultimately declined to comment for this article.

On Wednesday, the LBPD announced Luna had contracted COVID-19 at the beginning of the week and was in isolation.

We’ve done our best to include contemporaneous comments from Luna throughout this article. In the event that Luna or his campaign would like to respond, we will present those responses in a follow-up piece.

USE OF FORCE

In a presentation to the City Council last month that sounded like a preview of Luna’s campaign stump speech, he touted the great strides his police department has made in decreasing officer use-of-force incidents in recent years.

Between 2016 and 2020, he said his department saw a 50% decline in police shootings, a 28% reduction in use-of-force incidents, and a 30% decline in citizen complaints. Luna noted that these accomplishments were largely a result of over 100 policy updates since 2015.

But those figures don’t paint a complete picture of the department’s brutality against people of color, and especially Black people, according to Redmond.

“This city has a terrible record of abuse,” she says.

In May 2020, the Long Beach City Attorney’s Office reported that the city had spent more than $31 million since 2014 to settle 61 excessive force and wrongful death lawsuits against the LBPD. That’s more than Baltimore, Minneapolis, Denver, and Oakland paid out for police-related legal claims during the same period, all cities that have populations similar to or larger than Long Beach.

Due to the lag time between when the allegations occurred and when a trial takes place, a majority of the incidents that prompted those 61 lawsuits occured before Luna’s tenure as chief. Still, some of the costliest police killings and beating have occurred under his watch.

In 2017, a pair of Long Beach police officers shot and killed 37-year-old Sinuon Pream, a mentally ill Cambodian woman who was brandishing a knife in 2017. Attorneys for Pream’s family said that officers shot her in the back only 46 seconds after exiting their car. Then-Los Angeles County District Attorney Jackie Lacey, often the target of criticism for not prosecuting officers involved in use-of-force incidents, found that the two officers who shot Pream acted lawfully and they remained employed by the LBPD.

However, the fatal encounter later resulted in a $9 million settlement, the largest payout in a police shooting case in the city’s history.

Another point of contention is that the LBPD has a unique way of handling officer involved shootings, as is detailed in an investigation by the Long Beach Post. Rather than homicide investigators conducting recorded interviews with officers following a shooting as is advised by DA protocol, officers file statements which are then reviewed by investigators who may instruct officers on revisions. The original drafts of these statements are not made available. Administrators have denied any coaching on the part of homicide investigators to avoid incriminating statements but LBPD critics have balked at this assertion. Civil Rights Attorney Dale Galipo told the Post that he suspects officers don’t actually write their own statements.

The Post found that no other law enforcement agencies in Los Angeles County conducted police shooting investigations in this manner.

According to PoliceScorecard.org, which compiles law enforcement data on cities with populations of over 250,000, the LBPD is the worst-ranking police department in the state and fourth worst in the country. The website gave Long Beach police a failing grade based on a dismal score of 27 out of 100.

“Cities with higher scores spend less on policing, use less force, are more likely to hold officers accountable and make fewer arrests for low-level offenses,” the website explains.

In Long Beach, police killed 27 people between 2013 and 2020 and a Black person was over three times more likely to be killed by cops than a white person, according to PoliceScorecard.org.

In 74% of police shootings between 2016 and 2020, LBPD officers made no attempt to use non-deadly force before firing their guns, data pulled from the California Department of Justice and compiled by PoliceScorecard.org shows.

“I thought it was sadly fitting that the Chief of the worst-ranked Police Department in California on PoliceScorecard.org was running to take over the worst-ranked Sheriff’s Department,” Greg Buhl, an attorney who founded local police transparency website CheckLBPD.org, stated in an email.

Last year, we compared data on officers who were named in civil rights lawsuits closed between 2014 and 2019 and department payroll data. We found that the LBPD almost never fires officers involved in killing or injuring civilians, even after a civil jury finds that the officers in question violated a person’s rights. Moreover, some of these same officers go on to receive promotions, bumps in their paychecks, and even commendations.

Our investigation found that the LBPD promoted at least 12 officers to the rank of sergeant or lieutenant who had been named in legal complaints alleging unjustified police shootings and beatings, as well as wrongful arrests.

Downing, a former LAPD deputy chief, also said the LBPD was slow to end the use of the carotid restraint, a technique that cuts off blood flow to the brain by applying pressure to the neck and which can cause the person being restrained to lose consciousness.

The LBPD issued a special order banning the restraint on June 9, 2020, following the murder of George Floyd. This was ahead of a state ban that was at the time making its way through the California legislature and had garnered support from Gov. Gavin Newsom. But by then, most police departments in California had already banned or restricted the hold, according to a survey by the California Police Chiefs Association.

The carotid restraint has come under scrutiny for decades, with calls for its ban going back to at least the early 1980s. While the Los Angeles Police Department and the LASD both officially banned the hold around the same time as Long Beach, the Los Angeles Police Commission first placed restrictions on the maneuver in 1982—only to be used “where there is a threat of serious bodily injury or death”—following multiple deaths from chokeholds, including James Mincey Jr., a 20-year old Black man who fell into a coma and died two weeks after being placed in a carotid restraint.

Up until the special order, Long Beach police brass had classified the carotid restraint as an “authorized restraint hold.” Months before the ban, Deputy Chief Erik Herzog called it a “great tactic,” but said that officers were instructed to use the hold as a “last resort.”

“[Luna] had to wait until there was a scandal and pending legislation to [ban the hold],” says Downing. “Changes only come as a result of public outrage, not [as a] result of the vision of Robert Luna. He made no proactive moves to change this department.”

TRANSPARENCY

During his campaign announcement, Luna criticized incumbent Sheriff Alex Villanueva, who’s seeking a second four-year term, for ignoring subpoenas by oversight officials. Instead, Luna vowed to be a more transparent sheriff. But calls for increased transparency have been recurrent throughout Luna’s tenure leading the LBPD.

In 2018, Long Beach police made international headlines when it was revealed that the department, including Luna, had been using a self-deleting messaging app called TigerText for nearly four years. Al Jazeera learned from unnamed sources within the department that the app had been used to “have conversations that wouldn’t be discoverable.”

Internal police emails and financial documents from the city showed that the app was being used by over 100 police personnel. TigerText’s default settings deletes messages after five days, potentially destroying critical evidence that could be used in criminal and civil proceedings including those relating to officer-involved shootings.

“When police officers use self-deleting messages, they diminish the public’s ability to ever fully know about and challenge the government systems they are subject to,” wrote Mohammad Tajsar, a staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California, in a blog post about the scandal.

Luna told the LA Times that allegations that the app was used to transmit messages that would not be discoverable were false and that there was no intention on the part of department officials to destroy evidence.

TigerText was first utilized under Luna’s predecesor Jim McDonnell. McDonnell left Long Beach in 2014 to become LA County Sheriff but was ousted by Villanueva in 2018. Then-Sheriff McDonnell told the LA Times that he was unaware of the app’s self-deletion feature and would not choose to use it in the future.

Shortly after the exposé, the LBPD stopped using the app. Downing said it was telling that the LBPD killed TigerText almost immediately after its use became public and questioned why Luna didn’t make it a point to support his department’s use of the app if it was above board.

Downing was instrumental in breaking the TigerText story, working in tandem with Al Jazeera and the ACLU to obtain documents from the city showing the app’s implementation and purchase.

Best Best & Krieger, an outside law firm, was later brought in by the city to investigate the police’s use of TigerText and issued a report that found no wrongdoing by the department. At the time, the firm was under contract with the city as special counsel in an unrelated case, which has to date yielded $700,000 in legal fees.

“The widespread use of ephemeral messaging in society at large serves to make its use by the PD less exotic and frankly less ‘questionable,’ making apprehension around its use naïve,” attorney Gary Schons wrote in the city commissioned report, which compared TigerText’s ephemeral text messaging to a phone call.

Civil rights attorneys have questioned that legal justification. Attorney Thomas Beck, who has litigated against the LBPD over a dozen times in his 40-year career, told the Beachcomber that the comparison was “disingenuous.”

Verbal communication disappears, Beck explained, “but when converted to the written word, say for example a speaker dictating his thoughts into a phone for text messaging, it indisputably becomes a ‘record’ subject to retention and disclosure rules.”

Downing referred to the TigerText investigation as a “whitewash.”

One LBPD source told Al Jazeera that they witnessed the app being used during an investigation into the fatal police shooting of Jason Conoscenti in 2014. Long Beach Officers Eric Barich and Salvadore Alatorre, falsely believing that Conoscenti had assaulted a sheriff’s deputy with a deadly weapon, shot him as he ran away from police following a pursuit and lengthy stand-off. Prosecutors declined to criminally charge the officers involved, citing “insufficient evidence,” but the city settled a wrongful death lawsuit brought by Conoscenti’s aunts for $2 million. Alatorre was fired in 2019 after numerous excessive force cases resulting in huge cash payouts by the city.

The legality of police use of ephemeral messaging apps is still being debated across the country.

“There’s also the destroying of records before SB 1421 went into law,” says Redmond. “Long Beach destroyed a ton of records before that law went into effect.”

In 2018, days before SB 1421—a statewide transparency law that opened up certain police misconduct records for the first time—was set to go into effect, the LBPD purged a 23-year backlog of internal affairs records. While police administrators claimed at the time that it was merely a matter of clearing up storage space, internal emails we later obtained showed that Luna and other police brass were circulating messages from outside attorneys advising them to shred records ahead of the new law.

That New Year’s Eve—hours before SB 1421 came online—DA Lacey blasted out a plea to police chiefs and sheriffs in her jurisdiction, urging them to stop purging records.

“Information in these files could be useful in resolving wrongful conviction claims subject to review by the District Attorney Conviction Review Unit,” Lacey wrote. But by then, it was too late for Long Beach. The records were gone.

Months after the measure had been in place, Luna complained to the City Council that disclosure of officer disciplinary records under SB 1421 and another law requiring the speedy release of body camera footage were straining department resources.

In a memo to city leadership, he called SB 1421 the “most labor-intensive and fiscally-challenging mandate we have faced to date,” reporting that $62,000-worth of staff time had been spent reviewing records for disclosure. He requested additional personnel on top of the LBPD’s budget being $259 million—taking a 45% share of the city’s general fund.

“We’re under the gun, literally,” Luna told the council in 2019.

Later that year, the Long Beach Police Officers Association placed a provision in its labor contract that would require an officer to be notified when they are the subject of a public records request. Officers would also be given the name of the requester and the records being sought. Critics said this would only work to block or delay the release of the documents.

When it comes to dealing with researchers and journalists, the LBPD has a long—and frustrating—history of stonewalling. Time and time and time again, the LBPD has refused to produce public records and answer probing questions.

While Luna has criticized Villanueva for thumbing his nose at subpoenas, it’s worth noting Luna has never been subjected to that level of accountability. That’s because Long Beach’s own police oversight body, the Citizens Police Complaint Commission, has never once in its 31-year history exercised its own subpoena power to compel a witness to testify before the panel since officers are not legally required to show up. One former commissioner referred to the CPCC as a “farce” last year.

DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES

While announcing his bid for sheriff, Luna said that restoring trust would be part of his five-point plan should he be elected.

But in Long Beach, Luna’s police force has a record of discriminating against the city’s most marginalized communies.

Tomisin Oluwole

Face the Music, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 36 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Data analyses of LBPD traffic stops have shown that Black people in Long Beach are most prone to be detained and searched by police, no matter what form of transportation they take. Black drivers, cyclists, and public transit riders have all been found to be disproportionately targeted by police.

Luna, along with some of his rank-and-file, is currently a defendant in a civil rights case brought by a Black couple who allege they were racially profiled when officers stopped them to check for their fare. One of the plaintiffs, Kathleen Williams, ultimately spent two days in jail before being released without charges being filed.

Police executives are included as defendants in police misconduct complaints when a plaintiff’s counsel argues that systemic problems within a law enforcement agency had some bearing on the allegations. Notably, Luna has also been named as a defendant alongside his officers in three other civil rights cases that were later settled, together costing the city $5.8 million.

“The last thing I would ever say about Robert Luna is that he had a good relationship with the community,” said Redmond.

Luna has said the opposite, lauding the creation of a Community Advisory Committee. Launched in February, the committee’s ostensible purpose is to “review policies that impact community-police interactions.”

But Redmond says no attempt was made to include BLM-LB in those efforts.

“Why would they want to talk to us?” Redmond asked incredulously. “They want to ignore the people that are actually showing up to meetings and complaining about them.”

Apart from Long Beach being a city that is predominantly populated by people of color, it has one of the state’s largest LGBTQ+ populations.

Yet for the first year-and-a-half of Luna’s tenure as chief in Long Beach, he allowed a decades-old practice of entrapping gay men for lewd conduct charges. These police sting operations were only stopped after a Los Angeles Superior Court judge called them out as discriminatory in 2016.

At the time of the ruling, Luna told the LA Times, “We are 100% committed to civil rights and equality for all people, including the LGBTQ+ community.”

More than two years later, an assessment of the LBPD by law enforcement consultants, released only in draft form, found that the department did not have any policies addressing police interactions with LGBTQ+ individuals. This still remains the case today.

CREEPING SURVEILLANCE

Between June 2020 and May 2021, over half of the LBPD’s $14 million vendor spending went toward surveillance technology, according to a report from Just Futures Law and the Long Beach Immigrant Rights Coalition.

“Over the past decade, the Long Beach Police Department has steadily expanded its use of surveillance technology, with alarming implications for Black, immigrant, and people of color communities,” the report warns.

Luna is Long Beach’s first Latino police chief. During his campaign announcement speech, he highlighted his upbringing in East LA, saying that he grew up in a “poor Latino immigrant family.” He’s previously said that his father was an undocumented immigrant.

Long Beach is a sanctuary city and is home to about 31,000 undocumented immigrants, according to a 2018 report from the New American Economy.

Yet late last year, FORTHE discovered that the LBPD was sharing data captured by its automatic license plate readers with the Trump Administrations’ immigration enforcement agencies. This sensitive data is so granular that it can be used to reconstruct the historical travel patterns of a vehicle with extreme precision going back years. Among the agencies that had a direct pipeline to this data was U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The data sharing violated state law, according to the American Civil Rights Union of Southern California, as well as the city’s public commitment not to cooperate with immigration officials.

The police department later told the LA Times that the data had been shared in “error.” In January, while speaking before the City Council, Luna publicly acknowledged the data sharing for the first and only time.

“I know there was a young lady earlier talking about the ICE incident, which we regret,” Luna said in response to a rebuke from an organizer with the Long Beach Immigrant Rights Coalition.

While the LBPD removed ICE from its list of data-sharing partners, scores of out-of-state and other federal immigration agencies still had access to it six months later. It wasn’t until the ACLU of Southern California sent a demand letter to the LBPD that the department limited data sharing to in-state agencies only.

If Luna is elected sheriff, he will oversee the Los Angeles County Regional Identification System (LACRIS)—a vast database of mugshots, which feeds into the facial recognition systems of law enforcement departments across the region. The database has been criticized by privacy and civil rights advocates who say arrestees not charged with a crime are never purged from this digital catalog of faces.

In 2020, FORTHE teamed up with Buhl and CheckLBPD.org for an investigation into the LBPD’s use of facial recognition, a technology which has been shown by multiple studies to be racially biased.

Public records obtained by Buhl revealed the department saw a roughly four-fold increase in facial recognition queries in 2020—over 2,800—when compared to 622 in 2019. This dramatic uptick was a result of the technology’s use to scan faces caught on camera in an effort to track down looting suspects during the May 31 civil unrest, the LBPD said.

“There were a whole lot of cameras out there,” Luna said at a press conference on June 1, 2020, the day after protests broke out around the city in response to the death of George Floyd. “And if you were looting we have your license plate number and we have your face. We’re coming after you and we’re going to arrest you.”

Additionally, our investigation found that the department acquired two commercial facial recognition apps without City Council approval under the pretense of testing their capabilities. However, there was evidence suggesting officers may have been using these systems for investigatory purposes.

One of those apps was created by Clearview AI, which inhabits something of an ethical gray area due to the invasive database they have created. The company has data-scraped 3 billion images—seven times the size of the FBI’s database—from public social media posts, press reports, personal blog pages, and websites like meetup.com, sometimes in violation of those site’s terms of service. The company’s chief executive officer was also found to have extensive ties to white supremacists.

The department reined in its unregulated use of commercial facial recognition platforms only after Buhl submitted a flurry of public records requests related to the LBPD’s use of the technology.

There is virtually no local regulation on the acquisition and use of surveillance technology by the LBPD and the department does not have a policy ensuring safe and constitutional use of facial recognition technology, according to Buhl.

“A wholesale ban is definitely preferable to secret use without any policy to guide safe or constitutional use, which was Long Beach’s policy for the last decade,” wrote Buhl. “There is no reason the LBPD could not follow Detroit PD’s lead and limit the use of the technology to serious crimes and require multiple levels of human review before armed officers are sent out [to follow up] on an algorithm’s match.”

HANDLING OF GEORGE FLOYD PROTEST

On May 31, 2020, over 5,000 people took to the streets in and around downtown Long Beach in response to the murder of George Floyd by an officer in Minneapolis and as part of a global uprising against police brutality.

Long Beach police began declaring the gatherings an unlawful assembly roughly two and a half hours into the protest. In an effort to disperse the crowds, police fired so-called less-lethal munitions at protestors. According to Luna, less-lethal rounds were fired only after bottles and other projectiles were thrown at officers, who were clad in riot gear.

We documented injuries ranging from contusions to a severed finger suffered by protestors, including a teen author and a doctor, hit by these less-lethal munitions. KPCC reporter Adolfo Guzman-Lopez, who was interviewing protestors that day, also had his neck ripped open by a less-lethal projectile fired by police.

As the evening went on, a comparatively small group of people in relation to the number of peaceful protestors, began looting stores in the downtown area, Cambodia Town, and North Long Beach.

During a contentious on-air interview the night of the protest, Luna sounded exasperated as live cameras captured people breaking into the Jean Machine store at the City Place shopping center.

“Yes, we have a significant challenge tonight, but you know what, our police officers and many other police officers that have come into the City of Long Beach are going to be strong tonight and are going to get the job done and we’re going to be fine,” he said in the interview with Fox 11.

By the end of the night, 103 people had been arrested (74 for curfew violations), dozens of businesses had been broken into or vandalized, scores of less-lethal rounds had been fired at protesters by police, and National Guard troops were roaming the streets of downtown.

The handling of the protest by the LBPD was widely panned by different factions in the city. Demonstrators took to social media to denounce police’s heavy-handed tactics against them while business owners questioned why police hadn’t acted more proactively to stop the relatively small amount of people who were looting instead of focusing on peaceful protestors.

Even the LBPD’s own rank-and-file complained behind-the-scenes about being outnumbered and unprepared.

The following month, Luna defended his department’s performance before the City Council’s Public Safety Committee.

“We had some of our best people planning and organizing our response. And I actually believe they did a very good job,” Luna said. “If we knew what we knew today, several weeks later, 20/20 hindsight, could we have done better? Potentially.”

Luna told the Committee that on the day of the civil unrest, the crowds ballooned beyond police’s expectation of several hundred to several thousand.

Unlike Los Angeles and Santa Monica, Long Beach did not commission an independent review of its police department’s response to the protests.

PANDEMIC PROTOCOLS

COVID-19 killed more police in 2020 and 2021 than any other work-related cause. In fact, the coronavirus killed four times more police across the country than gunfire during that span.

One of Luna’s promises to voters has been that he would fire deputies who refuse to adhere to the county’s COVID-19 vaccine mandate. Yet his own police force was slow to get jabbed. As of Dec. 27, the vaccination rate among sworn LBPD officers was only 60% compared to 84% of all city employees who were surveyed. Moreover, critics have called into question Luna’s leadership on this issue after he orchestrated a “super-spreader” event during the height of the pandemic.

The Long Beach Post reported that on Nov. 5, 2020, roughly 300 officers assembled in the Long Beach Convention Center to take a group photo and listen to a speech from Luna without being ordered to stay masked. While an official photo shows a large gathering of mostly masked officers, other photos that became public show large groups of unmasked officers commingling.

It was later reported by Downing that the city’s Citizen Police Complaint Commission considered two charges of conduct unbecoming of a police officer against Luna. However, it’s unclear if those charges were related to the so-called superspreader event or if they were sustained because CPCC recommendations are not individually disclosed to the public and must ultimately be approved by the City Manager.

ON VILLANUEVA

While LBPD critics are not enthused about Luna’s record, they are no fans of Villanueva either.

With Luna racking up establishment Democrat endorsements and possessing more name ID than other candidates to jump into the crowded field it’s possible we could see the two in a run-off come November—though we’re still months away from a candidate filing deadline in a year-long election cycle that could contain an eons-worth of gaffes and revelations. For Downing, this would be a political scenario American voters know all too well: a dangerous disruptor (Villanueva) and weak-kneed establishment candidate (Luna).

“My opinion is that Villanueva is a thug … He’s been a rogue his whole life,” says Downing. “You got the guy in the back of the roll-call room who chips at management. Now he’s sheriff and he’s chipping at the Board of Supervisors.”

On the other hand, Downing says Luna would go along to get along.

“Luna is just the opposite. Luna’s gonna go along with the program. If a politician wants something, Luna’s gonna do it,” Downing said. “If Villanueva is re-elected, things will get worse … If Luna is elected, things will stay the same.”

Because BLM members advocate for the abolition of police rather than institutional reforms, Redmond says her organization will not be endorsing any particular candidate in the sheriff’s race.

“The one thing that we hope for,” says Redmond, “is that [the] sheriff is vested in the community, is committed to community improvement, and doesn’t see members of the community as innate criminals and is willing to accept and understand what a department can be if dollars are properly directed to social programs that improve the lives of community members.”

With adequate social services, Redmond argues, there will be no need for departments the size of the LASD or the LBPD. Mental health and domestic violence, she says, are better handled by mental health professionals than by law enforcement.

“Communities are poor and suffering in these cities, in part, because the police budget is too damn big and those monies can be reprioritized … We have to reimagine our public policy.”

The branding of a progressive sheriff, as indeed Luna has adopted and Villanueva before him, is a dubious one to Redmond. “What is a progressive sheriff?”

Updated at 12/30/21 to reflect that the Citizen Police Complaint Commission has never used its own subpoena power to compel a witness to testify before the panel.

joe@forthe.org

joe@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores