Community in Action: Mask-making, food distro, elder care, and other collective efforts in response to COVID-19

by Erin Foley | Published April 17, 2020 in Journalism

18 minute read“There wasn’t much time to think, we kinda just jumped into action,” said Micaela “Micky” Salatino, director of the Long Beach Time Exchange (LBTE).

With the onset of the shelter-in-place order in mid-March, people like Salatino across Long Beach quickly began looking for ways to help. Salatino’s friend Ofelia Rivera heard there was a shortage of masks, and more of a demand with the rise in coronavirus patients.

“Ofelia is one of our star members. She reached out to plant a seed after being inspired by North Orange County’s community mask-making efforts; wanting to do the same here,” Salatino said.

Rivera knew that Salatino, like her, had sewing skills and resources and, through the LBTE database, also had the contact information of many other people who did as well. She wondered what the Time Exchange could do during this time to stay aligned with their mission to “connect unmet needs with untapped resources.” When Ofelia mentioned the shortage of masks, she immediately knew how the LBTE could be of service. With their powers combined, they have been able to produce and deliver almost 900 masks since they started on March 23.

“We can do it from home, cutting fabric, sewing masks, delivering masks, delivering materials,” Salatino said. “It was a perfect fit, we already have a list of people that sew, so why not?”

Rivera had worked alongside Salatino and other LBTE members at a number of philanthropic “Repair Cafe” pop-ups, an event where people can bring items such as household appliances, laptops, or clothing to get fixed for free. Salatino had spent the majority of her working hours organizing community service gatherings such as these for the community.

To get started, Rivera and Salatino began researching mask-making, while also putting out the word for others to join using the hashtag #LBCmakers and creating an event page titled “Calling All Makers: Face Masks Needed.” Together, they gathered information from the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO), and local government, and brainstormed with other mask-making groups to come up with best practices. We Love LB, another local non-profit, sent them a tutorial, and since then at least three new makers have joined the cause each week.

Recipients have included a wide range of people: a group of chemotherapy patients at Memorial Hospital, two College Medical Center locations, The MHA (Mental Health America) Village, Kaiser Permanente nurses and doctors, Harbor Area Farmers Market workers, Menorah Housing Foundation (Long Beach senior housing) workers and residents, Maritime Couriers, and the list continues to grow.

Requests from families with small children, elderly caretakers, and those with auto-immune issues have also been coming in to their Facebook page. Salatino is managing and coordinating the logistics and the outreach to those who may be in need and those who have materials to donate, while Rivera has been making deliveries all around town.

Both have been sewing up a storm, with their design evolving over time as they learn more about what works, what is comfortable, and what is doable. Proper filtration has been a hot topic on social media and in the news. A piece of paper with the words “Put Filter Here” is placed protruding out of the pocket of the mask so it can be easily seen and the recipient knows to insert the filter of their choice. Some people are adding HEPA vacuum bags or reusable shopping bags cut to fit, a double layer of “blue shop towels” (used to clean up grease in auto body shops), or PM2.5 activated carbon filters. #LBCmakers have instructed their makers to make the masks with a different fabric on each side, so that it was clear which side went against the face and which should be facing outward. The new mask owner is also instructed to rewash them before wearing.

Porch-to-table

Director Kristen Gritter-Cox jokes about how familiar most of Long Beach has become with her front porch due to the pounds of produce, non-perishables, clothing, and hygiene products that have been left there since the Long Beach Community Table (LBCT) began in September 2018.

Since mid-March, the LBCT has been trying hard to keep up with the logistics of feeding an ever-increasing number of people. Prior to the coronavirus, their volunteers would head to parks to reach those experiencing food insecurity. They’ve had to modify their operations to comply with social distancing measures, while scaling them up to meet the growing demand.

“The need just keeps increasing. Before it was about 6,000 pounds a week, now we are up to 8,000 to 10,000, with far more deliveries to homebound people. But we’re getting a lot of new sources of donations, too,” said Gritter-Cox. “We are really in need of a larger warehouse at this point.”

Fortunately, she says LBCT was recently one of five organizations awarded a $20,000 grant through the Coronavirus Relief Fund offered by the Long Beach Community Foundation in partnership with the City of Long Beach. Grants are being accepted by the foundation on an on-going basis and are reviewed weekly.

Last year LBCT distributed 300,000 pounds of food donations, on top of hygiene products and clothing, to a long list of housing and/or food insecure people.

Tomisin Oluwole

Fragmented Reflection I, 2021

Acrylic on canvas panel

24 x 30 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

According to their Facebook page, their mission is to be a “platform for building mutually beneficial community connections,” which they do by collaborating with other organizations “to collect and deliver affordable, nutritious, organic foods directly to those without access.” In the past year, they were able to secure a small warehouse on the north side to store their inventory, and partner with groups like the LBTE to provide crop swaps and repair cafes on site.

Serving the elders of the community

Tahesha Christensen is used to spending her time working to protect the local wetlands and Puvungna, the sacred meadow on the east side of Long Beach—the place of creation for the native Tongva and Ajachemen people. But when the pandemic hit, Christensen worried about the elders of the community and shifted to organizing deliveries of supplies such as fresh organic produce, dried goods, non-perishables, and toilet paper.

Calling it Wathin’ethe (AKA 100 Acts of Kindness) she started an “indigenous led community-based grocery delivery service for those in need during the COVID-19 pandemic.” The name is a cultural term from the Umonhon/Omaha Nation, of which Christensen is a member, that “refers to a rite of passage that involves performing 100 acts of kindness to demonstrate or achieve leadership.”

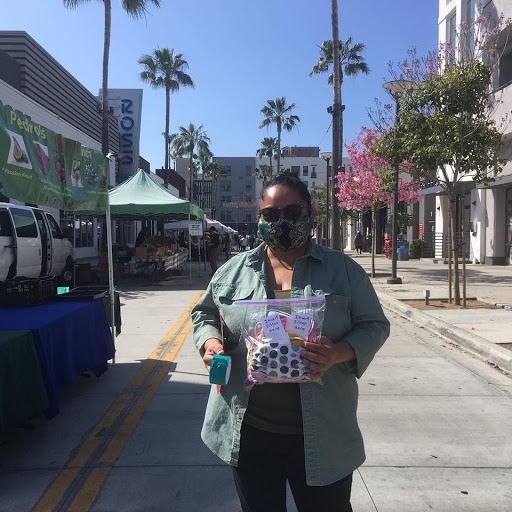

Though the collective is mainly made of Native women, including local musician Malila Hollow of the Yankton Sioux/Assinaboine tribe, Yulu Ewis of the Confederated Indians of Graton Rancheria, and Megan Marie of the Acjachemen tribe, Christensen wanted to make it clear that their intention is to help anyone in need, not just the native communities. She gives credit to a Tongva/Acjacheman elder named L. Frank who lives in the Bay area. It was important to Frank that Christensen help all but frame the current issues in the context of traditional native values.

“L. Frank is the heart of it; it was her vision,” said Christensen. “She said everyone needs it but also wanted me to put it in my own cultural context.”

They recently partnered with Paula June Cantu and the LA-based non-profit ICAN Project, which works with native communities across the country. As the collective has grown, so has its ability to help a wider range of people with a wider range of items including face masks, cleaning products, adult and baby diapers, children’s toys and games, and more. With connections in LA, Long Beach, as well as the Inland Empire, Sacramento, and the Bay Area, Christensen encourages the public to reach out via social media and express their needs.

“We are doing social distancing drop-offs for people who are housebound, seniors, struggling families, mobility challenged and autoimmune individuals, students, and people who lost work, including art and music gig-dependent people,” Christensen said. “We are empowering our community to act on kindness and contribute donations and skills in a way that builds community-based on giving and receiving. Many of the people who received, then gave back in small ways, too.”

Caring for neighbors over the internet

Before the pandemic, Crystal Ortiz, with her Twice New Foundation, would take leftover items from big events and prevent them from being trashed by distributing them to people in need. But then, of course, the entire event industry essentially came to a grinding halt.

And so, Ortiz had to come up with a new plan while she sheltered-in-place in her downtown Long Beach apartment.

She soon made it her goal to use resources from Twice New to provide at least one meal per day to someone in need for the duration of the stay at home orders. She said it pained her to see so many of her favorite restaurants struggling to keep their doors open, and wanted a way to support them while also helping out someone who could use it.

Having just moved here two years ago, she also wanted a way to stay connected to her neighbors. Inspired by the community building she saw happening on the Long Beach Food Scene Facebook page, she started her own group, Long Beach Locals.

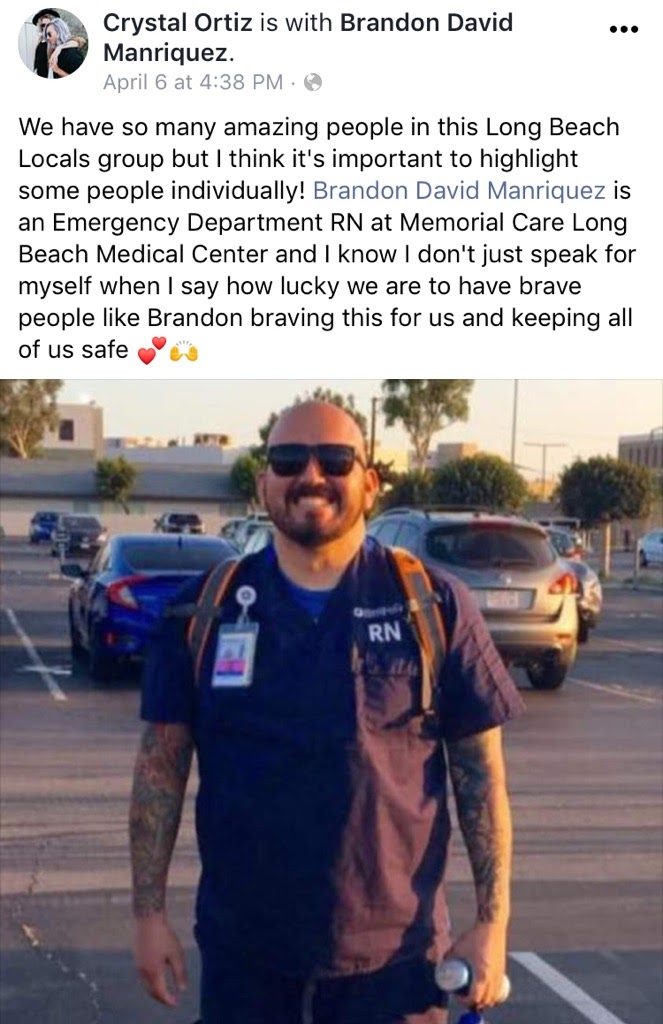

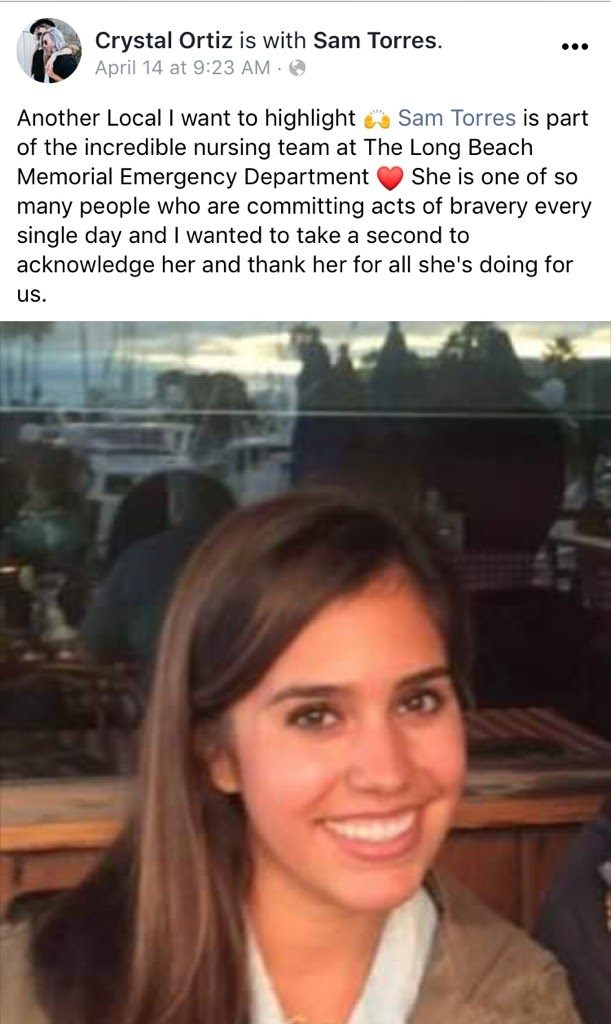

In order to let the public know what local food-makers were doing to adapt to the current needs of the community, she started recording Zoom calls with the likes of small businesses such as Primal Alchemy, The 4th Horseman, and Rainbow Juices, so they could talk to the public directly. When not sharing her video interviews, Ortiz also takes the time to put a spotlight on the often faceless individuals working the front lines.

Locals on the page banter about food choices and photos of California poppies in bloom and other light-hearted fare, but also touch on serious topics like mental health resources and the news of the day.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

- Margaret Mead

With their grassroots efforts to share resources and help people feel less alone, each of these “thoughtful, committed” humans are surely putting into action the oft-quoted words of anthropologist Margaret Mead, whether a citizen or not. We are lucky that these are just a few of the many small groups in Long Beach doing their best to change the world.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

erin@forthe.org

erin@forthe.org