City Tacitly Acknowledges Oceanaire Deal Lacked Safeguards, Could Double-Down on ‘Workforce Housing’ Model

11 minute readLong Beach could soon see additional luxury apartment buildings being purchased and converted to “workforce housing” under the same controversial financing model used to buy the Oceanaire last year.

In August, we published an exposé detailing how a real estate transaction intended to convert the Oceanaire, a 216-unit luxury apartment complex in downtown, into affordable housing was a risky move that could end up providing little public benefit in exchange for millions of dollars in tax subsidies.

The multi-pronged deal saw the California Statewide Communities Development Authority (CSCDA), a joint powers authority, issue $135.7 million in tax-free bonds to purchase the Oceanaire. Because the CSCDA is a public agency, the building became exempt from property taxes once the sale was finalized—a tax subsidy estimated to be worth $43 million over 30 years, the maximum term of the deal.

Theoretically, taking the Oceanaire off the tax rolls cuts operating costs enough to allow that extra cashflow to be put toward reducing rents for tenants, who must earn between 80% and 120% of the area median income to qualify for a unit. For a family of four, that translates to between $90,000 to $135,000 a year.

But not everyone was sold. Prior to the Oceanaire deal being inked, city-hired consultants HR&A Advisors wrote in a memo that the transaction would leave Long Beach with “modest affordability benefits, a financial structure that is misaligned with City interests, and a return on public investment that does not provide clear justification for participation.”

The consultants found that the amount of property taxes being siphoned away by the deal exceeded the aggregate rent savings that would be produced.

Waterford Properties, which oversees the day-to-day operations at the building, has argued that since the Oceanaire’s purchase, apartments have been leased to city employees, first responders, teachers, accountants, and other professional-class tenants who might have otherwise moved out of Long Beach.

Currently, one-bedroom units at the Oceanaire are going for $2,592 a month. Earlier this month, Forbes reported that studios were being advertised starting at $2,351, more than the neighborhood’s market rate.

And Long Beach could soon see more of these deals crop up.

At its next meeting the City Council will consider creating a framework for joint power authorities, like the CSCDA, to apply this complex financing model to additional properties. In contrast to the Oceanaire deal—done as a pilot run without any enforcement mechanisms for the city—this program would put in place certain guardrails to beef up the underwriting standards and public benefit of future transactions.

City staff is recommending that the council approve the Middle-Income Housing Program, which is accompanied by a term sheet drawn up by HR&A outlining parameters for future deals to be considered by the city. These requirements include:

- Cumulative rent savings over the life of the bond must be equal or greater to the total amount of foregone property taxes.

- The project must provide at least a 10% discount over current market rents for equivalent units.

- Affordability must be maintained for 55 years.

- A “host fee” must be paid to the city as reimbursement for lost property taxes. (This only accounts for a minority of the forgone property taxes. Other taxing entities that provide essential services to local residents such as the Long Beach Unified School District, Long Beach Community College, and Los Angeles County would still lose property tax revenue.)

- Fees paid to the parties involved in these deals must meet market standards.

- The financing structure must produce sufficient net revenue to pay debt payments.

Additionally, the city would reserve the right to review key aspects of the financials and affordability levels. The city must also approve any new debt over $50,000 put onto the project, as well as any ownership changes.

Even with these terms and conditions in place, HR&A warns that there’s a “default risk if market conditions and/or project management do not generate the required level of annual net income.”

That’s because even with these protections, this model, just like the Oceanaire deal, still fundamentally relies on unwavering rent growth throughout its 15 to 30 year term in order to make annual debt payments—an assumption known as “trended rents,” which critics have said is overly optimistic and makes these deals highly leveraged.

“The combination of these and many other transaction risk factors may temper the potential future financial benefit for the local government,” states the HR&A memo.

A report jointly authored by HR&A, CSG Advisors, and the California Housing Partnership in November warned California cities that the history of bond financings for rental housing is littered with defaults resulting from a reliance on trended rents and risky underwriting.

“This history of bond financings is sobering. When issuers have stretched normal underwriting standards to borrow more money or try to create affordability by taking on more risk the results have undermined – rather than strengthened – support for affordable housing,” the report advises.

This raises some major questions: Why is the city moving at such whiplash speed—relative to the typical pace of City Hall—to push through a financing model that nationally respected consultants continue to be wary about? And why did the council allow the Oceanaire deal to go through without the same set of safeguards now being put forth?

Tomisin Oluwole

Face the Music, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 36 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

While the proposed Middle-Income Housing program can be read as a tacit acknowledgement that the Oceanaire deal was severely lacking in basic oversight measures, the city staff report gives no indication of what has been learned from the pilot project, which has only had a leasing period of less than a year.

Instead, the city’s stated reasoning behind proceeding with the program is that Long Beach is being pressed by the state to create 4,158 units of housing for moderate-income households by 2029. Yet, that number is dwarfed by the 11,188 units the city needs to allocate for low- and very low-income households in that same span. This program does not address those needs.

The city staff report goes on to claim, without evidence, that moderate- and middle-income households are facing precarious and unhealthy housing conditions: “As rents and housing prices continue to rise these households have found housing to be out of reach. Unaffordable rents typically result in either overpayment, overcrowding, or both. When households overpay or overcrowd in order to obtain housing there are strains on their health, wellness, financial, and overall stability.”

However, all data indicates that it’s actually Long Beach’s low-income households that are most significantly impacted by overcrowding and overpayment of housing costs, not the income band served by these workforce housing projects.

According to the proposed Long Beach 2021-2029 Housing Element, “Housing cost burden and overcrowding continue to disproportionately impact the City’s lower income and minority households.”

In fact, HR&A even noted in their February memo to the city that “the housing cost burden for moderate income households in Long Beach is much lower than in the rest of Los Angeles County or California more generally.”

So what other reasons could explain the city’s rush to gamble millions of tax dollars on a potentially risky housing scheme that may not even be serving an urgent need? There’s certainly lots of money at stake.

Forbes, generally a business-friendly magazine, recently described this financing structure as “America’s most notorious junk municipal bond peddlers … getting rich off California’s affordability crisis.”

More than $6 billion have been issued by joint power authorities to acquire over 35 apartment buildings for these workforce housing deals in cities across the state. The CSCDA, which unlike a typical public agency is largely a collection of consultants, lawyers, and asset managers, will make at least $2.1 million in fees over the course of the Oceanaire deal.

Some critics have also noted that at least some of these deals smell like bailouts for luxury apartment builders who are seeing slumping occupancy rates and want to get out of the game without losing their investment.

“The Oceanaire was slow to lease up as a market rate property with occupancy well below 95 percent,” reads HR&A’s most recent memo.

But it’s not just the bond issuers and the sellers who are raking it in. The deals also involve a developer, which acts as the “project administrator” and oversees the property management company at these converted buildings.

In the case of the Oceanaire, that developer is Waterford Properties, a well-connected firm notorious for displacing low-income tenants in Long Beach. The company stands to make $11.5 million over the next 15 years in fees off the Oceanaire deal while taking on little to no risk, according to an HR&A analysis.

And there seems to already be interest in purchasing and converting additional buildings using this model.

Under the timing considerations section of the city staff report for Tuesday’s council item, it vaguely states: “City Council action is requested on January 18, 2022, to allow pending Program applications to be considered.”

An inquiry to the city for more details about what properties are in the crosshairs was not returned by press time.

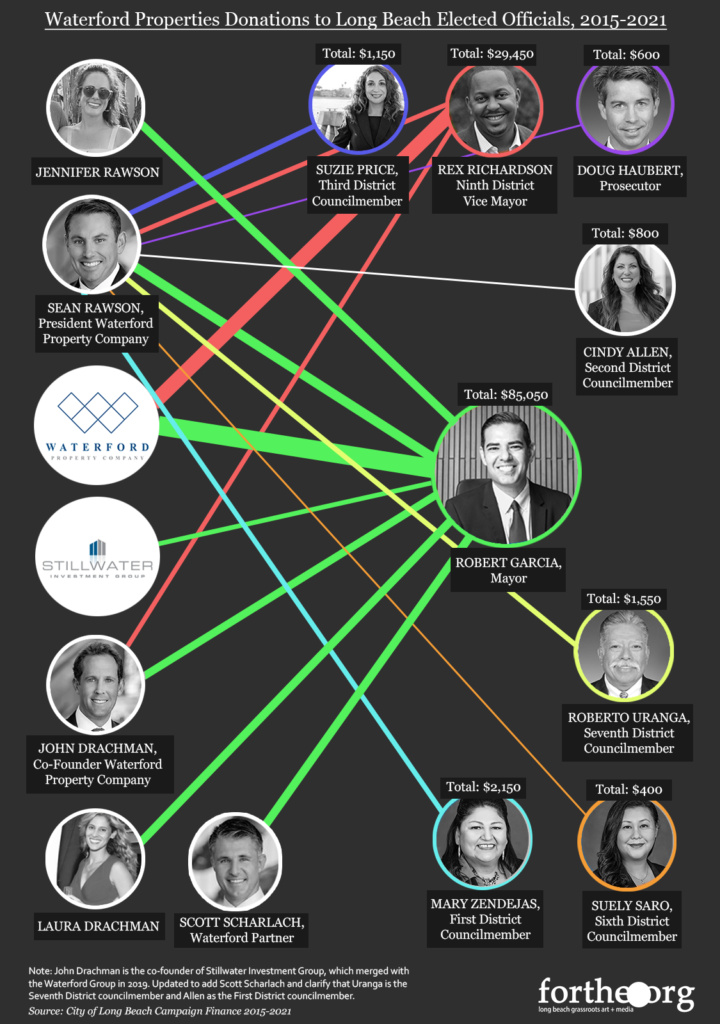

Waterford, its executives, and their wives have become a firehose of political contributions to the campaigns of Long Beach elected officials. The two biggest benefactors of these bundled donations have been Mayor Robert Garcia and Vice Mayor Rex Richardson, according to an analysis of campaign finance records.

Garcia, who is running for Congress, has received at least $85,550 from Waterford and individuals tied to the company since 2015. Richardson, who is running to replace the mayor, has gotten at least $29,450. And with the pair both engaged in competitive races with increased contribution limits over their current offices, there will certainly be the opportunity to collect more.

The City Council meets at 5 p.m. Tuesday. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 surge, the meeting will be held over Zoom.

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores