Redistricting, Rebuttals, and Retorts: Support for Citizens Redistricting Pushes Forward; Some Still Aren’t Sold

10 minute readFrom the Editors: This piece kicks off our election coverage that will continue through the Nov. 6 midterms. We will be taking a closer look at both the local ballot as well as state races that affect Long Beach. Stay tuned and stay connected.

Time Until Election:

City leadership often lauds Long Beach’s large population of Cambodian descent—possibly the largest outside of Cambodia. But after over 50 years of residence in Long Beach, this community of roughly 50,000 to 70,000 (estimates vary) would like to see a Cambodian-American elected to the city council for the first time.

First they have to consolidate themselves into one city council district. Cambodia Town is currently split between Districts 1, 2, 4, and 6, thereby diluting its power as a voting block.

Organizers point to a provision in the current criteria that states “splits in neighborhoods, ethnic communities and other groups having a clear identity should be avoided.” They believe the city has been in clear violation of this rule by breaking up Cambodia Town.

Born largely of refugees fleeing the brutal Khmer Rouge—which carried out a genocide that killed millions—many members of the Cambodian community, especially the elders, are unfamiliar with a system where political power is acquired through organizing and petitioning the government.

That makes the accomplishment of successfully lobbying for Measure DDD all the more impressive. If passed, DDD would place the power of drawing city council district maps in the hands of citizens, a change Cambodians for Equity—a coalition of 14 organizations pushing for independent redistricting—hopes will allow for greater representation of their community.

“I’m proud of my Cambodian community,” said Dr. Tang Song, President of the Cambodian Health Professionals Association of America and Board Member at the MAYE Center. “We’re on the front line.”

While Cambodians for Equity and partnering organizations’ support for Measure DDD pushes forward, another newly formed group wants to see it, along with three other mayor-backed ballot measures, fail.

“We feel both the Ethics Commission and Redistricting Commission ought to be beyond reproach,” said Carlos Ovalle, Executive Director of People of Long Beach, “without the slightest appearance of impropriety. As it stands, given the selection process, neither do.”

Last week, they were taken to court by the city over the wording of their ballot argument against the measure. While an agreement was reached, a newly formed political action committee and coalition of neighborhood groups held a press conference on Thursday making their opposition clear.

“I’m here to say, I want a different kind of government,” said Robert Fox, the Executive Director of the Council of Neighborhood Organizations, and a member of the Long Beach Reform Coalition. The group is an amalgamation of various neighborhood and advocacy organizations including the aforementioned PoLB and CONO, along with Long Beach Neighborhoods First and the Long Beach Taxpayers Association, among others.

Good Government

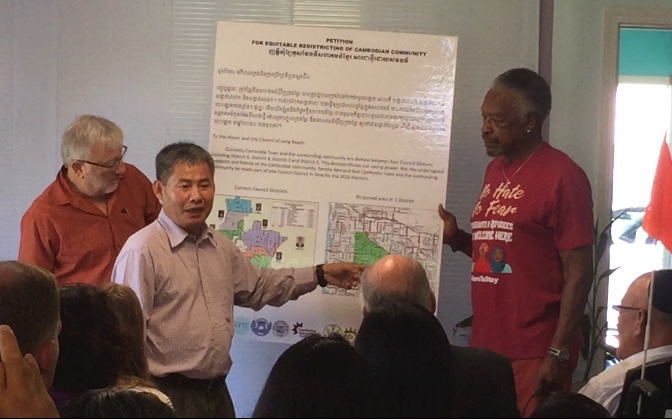

It’s a Saturday morning in Cambodia Town, early last month. Inside a homey community center full of traditional Cambodian artwork and houseplants, long-time civil rights attorney Marc Coleman gives the crowd a brief history on the structure of Long Beach’s city council before diving into redistricting.

The town hall-style event was hosted by The MAYE Center, which partnered with Common Cause, a nationwide good government group, and was attended by community organizations, city officials, and business owners. This follows successful lobbying on the part of these organizations to strengthen the citizens redistricting charter amendment originally proposed by Mayor Robert Garcia.

About 30 people listened attentively to Coleman’s civic history lesson, which was translated into Khmer by Sereivuth Prak. It was here at the MAYE Center that Equity for Cambodians first blossomed. The center serves as a self-healing space and its membership includes numerous elders from the Cambodian community. Over time, civics classes were added to the schedule alongside the more typical yoga and urban farming classes.

Representatives from three of the four council districts that contain a piece of Cambodia Town sent representatives to the meeting. Only Councilmember Dee Andrews’ (CD-6) office was absent.

“This is a good government item that will inspire public confidence,” said Councilmember Al Austin (CD-8) while speaking at the event.

How it’s set up now, the city council redraws its own district maps following the release of the decennial U.S. Census. But that could change in November, when Long Beach voters could decide on handing the pen to a commission of citizens.

Dan Vicuña, the National Redistricting Manager for Common Cause, also spoke at the event, providing background on the process of redistricting. Citizen redistricting is one of the main issues Common Cause has been campaigning around.

“I used to call it the most important issue no one’s heard of,” said Vicuña. “That’s changing.”

Manipulating the redistricting process in order to benefit and/or negatively affect a particular party or faction is known as gerrymandering, and it’s a hotly contested issue across the country. Groups in Colorado, Missouri, and Utah have successfully placed initiatives on the midterm ballot which would in some way remove lawmakers from the process of drawing district maps. At the end of July, the Michigan Supreme Court upheld an independent redistricting commission initiative which was being challenged by a group funded by the Michigan Chamber of Commerce.

Tomisin Oluwole

Face the Music, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 36 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

But having a commission takeover redistricting is not a panacea all on its own. Vicuña discussed the ways in which citizen redistricting can be manipulated. While taking the responsibility of redistricting away from lawmakers is an obvious first step, Vicuña quipped that “not all citizens redistricting commissions are created equally.” Some ostensibly independent redistricting commissions can actually be subservient to the officials they are meant to check.

He pointed to the City of Los Angeles as an example, and laid out several elements that compromise its democratic function. The redistricting commission is advisory—district maps need to be approved by the city council before taking effect. Commissioners are appointed by the councilmember themselves, presenting a conflict of interest. There are no eligibility requirements such as equal representation of party registration, a background that would establish knowledge of government, or prohibition of recently elected officials from joining the commission. Finally, there are no transparency measures, such as a requirement that map deliberation must be made public.

“All reports indicate [that] the City of Los Angeles’s commission did exactly what the councilmembers [wanted them to],” said Vicuna.

When it was first drafted, the Long Beach charter amendment that would create a redistricting commission gave it many of these same undemocratic features: it was advisory, there were no established qualifications for commissioners, and it lacked transparency measures. Finally, commissioners were to be appointed by the mayor with confirmation from the council.

“It was so flawed,” said Laura Som, Executive Director of the MAYE Center. “It’s called Citizen Redistricting, but the power [was] still given to the mayor.”

A Community Responds

Organizers at the MAYE Center quickly realized that the first draft was a Trojan horse.

Equity for Cambodians, in collaboration with Common Cause, worked with city officials to draft new language that addressed many of their concerns. In the retooled version, commissioners are chosen through a ministerial process instead of being politically appointed. It’s a more convoluted process but one that the measure’s supporters say is more independent.

Here’s how it’ll work: The city clerk will be tasked with sending commissioner applications to all registered voters citywide who meet certain qualifications. Applicants will then be pared down to a pool of 20 to 30 people during a public meeting by a screening committee—comprised of the Ethics Commission, should one be established by passing the concurrent but separate Measure CCC.

The chair of the screening committee will then randomly choose nine commissioners from the pool of remaining candidates. Those nine will in turn select the four remaining members from the same pool they were picked from, forming a commission of 13.

Language was also added that places restrictions on commissioners (as well as their immediate family) running for office or participating in political activities during and after their tenure. There is a requirement that the applicant pool equally represent each city council district, which was a pressing concern for Cambodians for Equity.

Yet some are still unhappy with the language of the redistricting commission amendment. Brothers Carlos and Juan Ovalle of People of Long Beach, a newly formed group, voiced their concerns at the meeting: the measure entrusts the partially mayor-appointed Ethics Commission with selection of the Redistricting Commission. How then can citizens guarantee that the same subversion that would result from direct appointment by the mayor wouldn’t happen by extension of a mayor-appointed Ethics Commission? They believe that support for the measure should be rescinded until this concern is addressed.

Equity for Cambodians and Common Cause point to the qualifications for commissioners as a strong safeguard against political influence, even if they are selected by a commission that contains political appointees. Coleman and Norman assured the crowd that they will be diligent in monitoring the situation.

According to City Attorney Charles Parkin’s analysis of the Ethics Commission measure: “The mayor and city auditor would each appoint two members to the commission, to be confirmed by the city council. The remaining three members would be appointed by the initial four commissioners, following a public recruitment and application process.”

Carlos Ovalle of PoLB, echoed his organization’s comments from the community meeting at the last public hearing held for the charter amendments: “It cannot be an independent redistricting commission—even though the proposal is really good the way it’s been written. We can’t support it if it’s selected by the Ethics Commission.”

Ovalle clarified in a follow-up: “a majority of the Ethics Commission members (4 of 7) are selected by city hall, and these in turn select three others. This continues in perpetuity as the Ethics Commission is not self-generating. Then the Ethics Commission picks a majority (9 of 13) of the members of the Redistricting Commission.”

Coleman also spoke at the hearing. While criticizing the city for not facilitating public participation well enough, he also made note of the auspicious occasion. A long time critic of Long Beach’s city leadership, Coleman says this is the first time in over 35 years of advocacy that he’s been invited in to help shape legislation.

“We’[d] been working on [redistricting] for about seven months,” said Coleman. “We knew a lot about this. I was glad to see the unusual step of inviting us, as a community organization, into the process. It doesn’t often happen.”

He understands where PoLB is coming from. He’s been in their shoes most of his public life. But he offers advice.

“Get your facts straight,” said Coleman. He believes “selection” of redistricting commissioners by the Ethics Commission is being misrepresented by PoLB.

In an email follow-up, Alex Norman pointed to the official ballot rebuttal to the argument against Measure DDD, which Equity for Cambodians contributed to and says, “The Ethics Commission randomly picks nine candidates who have already been prescreened by the nonpartisan city clerk. These nine, one from each council district, would then pick an additional four to ensure the commission reasonably reflects the city’s diversity. That’s fair.”

If you appreciate journalism that doesn’t require a conflict of interest disclaimer, please consider supporting local grassroots media by subscribing to FORTHE.

joe@forthe.org

joe@forthe.org