The Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach: Advanced Cameras

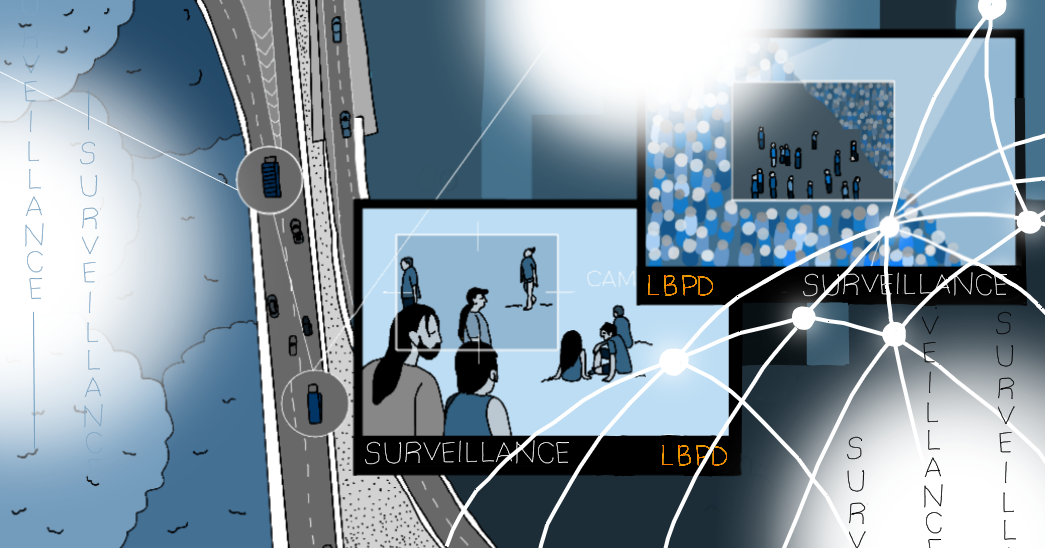

27 minute readFreedom Surveillance may sound like someone’s attempt to coin a new oxymoron—like jumbo shrimp or civil war—but it is actually the name of the Arizona-based company that manufactured the high-tech, truck-mounted camera the Long Beach Police Department deployed at a morning Peace Walk organized by Black Lives Matter Long Beach (BLM LBC) on July 3.

Freedom Surveillance is just one of many companies whose surveillance technology the LBPD has spent millions on in the last decade. This article will cover Freedom Surveillance’s technology and some of the other advanced cameras owned by the LBPD.

Future articles in this series will explore ten other categories of surveillance technologies used by the LBPD—closely tracking the work done nationally by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), the leading non-profit defending civil liberties in the digital world. In fact, it was submitting some Long Beach entries for the next update of the EFF’s Atlas of Surveillance (a recently launched database of the surveillance technologies deployed by law enforcement in communities across the United States) that helped catalyze this series of articles.

Government surveillance of individuals started long before the 9/11 terrorist attacks, but since then surveillance has grown at a concerning rate, with few checks on its growth. Programs that started as ways to prevent the next terrorist attack, with less adherence to the Constitution than one might want, have transformed into domestic crime-fighting programs that are not always as protective of privacy rights as they should be.

Extensive federal funding has allowed local governments to purchase technology that state and local legislature did not anticipate, with policy lagging years if not decades behind technology acquisition. This lack of oversight has meant that the work done by groups such as the EFF and media institutions has been one of the only checks on the otherwise largely unchecked growth of government spying on its citizens.

In terms of surveillance equipment, the LBPD is keeping pace with the most Orwellian police departments in the country, and has the distinction of being the only law enforcement agency ever caught using a disappearing text messaging app for official communication.

If you’re unfamiliar with the LBPD TigerText scandal uncovered in 2018 by Stephen Downing of the Beachcomber and reported on globally by Al Jazeera, do yourself a favor and read about that sometime soon—if not before you start this series. It puts these other technology acquisitions in context. Purchase documents show that many of the most significant technology purchases to be discussed were made while the LBPD was still using Tigertext to conceal communications—with the same officers who set up TigertText involved in the purchases.

While some police departments publicly disclose their surveillance technology, by choice or in response to local surveillance transparency ordinances, very little is known about the surveillance architecture the LBPD has established in Long Beach. This series of articles will examine local surveillance technology transparency issues—while examining how other cities in California have addressed the issues raised by technologies currently used by police in Long Beach. The majority of the information reported in this series will come from LBPD documents newly disclosed in response to dozens of public records requests submitted by FORTHE Media, plus documents already made public by records requests from other organizations.

FREEDOM ON-THE-MOVE TACTICAL SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM

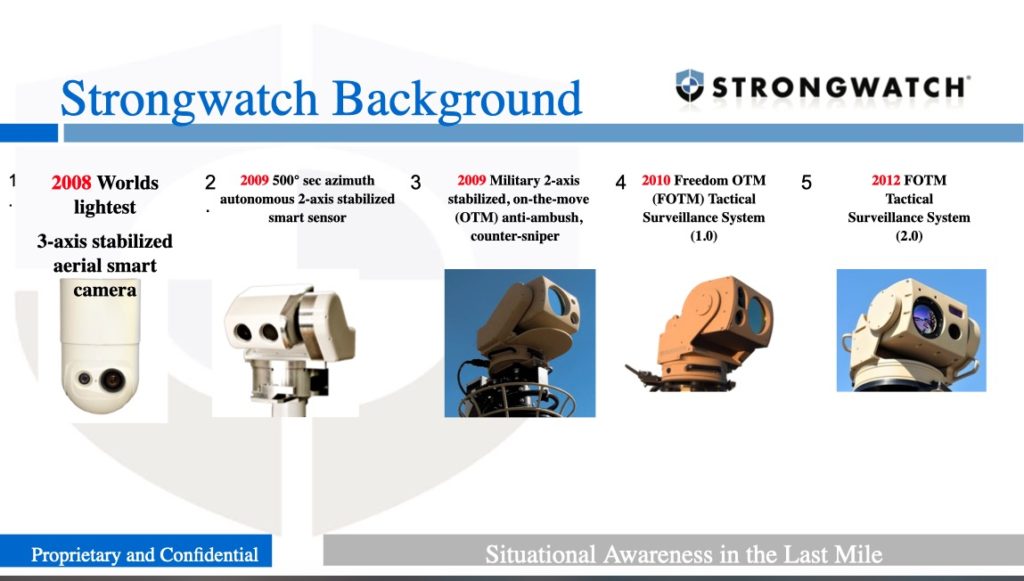

The Freedom On-The-Move (FOTM) tactical surveillance system is made by Freedom Surveillance, LLC, which does business as Strongwatch. FOTM and its related software and upgrades are the company’s core product. Comparing the marketing material turned over by the LBPD with the photo taken at the BLM LBC march, shows that the police department has the 2012 FOTM Tactical Surveillance System 2.0.

Promotional videos on the company’s website show its applications in border enforcement—with a truck much like the one above being able to navigate rugged terrain and deploy the covertly stored mast-mounted camera from a closed truck bed to track people at the border day or night. The BLM LBC Instagram post mentions the FOTM system as having listening capabilities, though the marketing material the LBPD produced makes no mention of such capabilities.

FOTM SYSTEM TECHNICAL CAPABILITIES

The Strongwatch/Freedom Surveillance website and YouTube channel feature a twenty-minute video showing some of the features of the system, like an “intuitive controller” (it’s an Xbox controller), visible and near Infrared (IR) laser pointing, range and elevation finder, thermal and night vision, and vehicle or human detection and tracking. Documents produced by the LBPD include a June 2013 white paper from the company describing the FOTM camera’s “other biometric capabilities (facial recognition, license plate recognition, etc.)” that can be enabled with third-party software.

The majority of the FOTM system’s marketing material describes its usefulness in more rural, open landscapes—with its thermal camera capable of detecting human targets at four miles, the ability to toggle between camera modes and fields of vision to scan the horizon, and an IR laser that can track targets four miles away. In an urban environment, where its human detection abilities are less important, the camera’s value likely comes from its ability to record high-definition video of a wide field of vision for later video analysis, its ability to track individuals with IR laser illuminators that are invisible to the naked eye, and its use in conjunction with facial recognition and license plate scanning programs.

IR laser illuminators and thermal cameras have previously been used to track protests in Ferguson, MO after the death of Michael Brown and in Baltimore after the death of Freddie Gray. In those instances, FBI spy planes—with local law enforcement on board—used aircraft-mounted Forward-Looking Infrared (FLIR) cameras together with IR lasers to track the protests from the air for 36 hours. The LBPD owns two aircraft-mounted FLIR capable of working with the FOTM system to conduct similar surveillance and has no policies to guide their use.

The license plate and facial recognition possibilities are confirmed by the PowerPoint presentation from Freedom Surveillance—also turned over by the LBPD—that describes “extensible software integration (HDT, LPR, FR).” HDT stands for high-definition thermal.

Future articles in the series will cover LBPD’s license plate readers and their facial recognition capabilities.

Three minutes into the promo video, the company shows a map of where its cameras have been deployed. The map shows seventeen cameras deployed in the US—mostly along the border.

The Long Beach FOTM camera is the third most northern camera, with units also located in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. The map also shows deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan.

The military origin and use of this technology are confirmed by the marketing material turned over by the LBPD, which include a PowerPoint Presentation with slides titled “Military Genesis” and “Battlefield Experience” and promote “counter-sniper, anti-ambush capabilities; giving the warfighter complete situational awareness in the ‘Last Mile’ of combat, day or night.”

Eight minutes into the video we see a FOTM deployment at the 2008 Pasadena Rose Bowl, which gives an idea of its crowd scanning capabilities. This Rose Bowl deployment is mentioned in the only previous media mention online about the FOTM, a 2018 article from the Arizona Republic. Although the article mentions it was used in Pasadena “to scan the rooftops for potential snipers,” the promotional video does not show any rooftop scanning and instead focuses on crowd scanning.

PROBLEMS WITH PAST FOTM SYSTEM DEPLOYMENTS

Protestors in Long Beach are not the only ones to be surveilled by a FOTM camera. In Arizona, protestors who were coming to a city council meeting to complain about their rough treatment and tear gassing by police at their counter-Trump rally had to walk by a FOTM truck that had been posted in front of the meeting on the day they planned to address the council.

In discussing the chilling effect this technology can have on free speech, Will Gaona, the policy director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, said, “the department parked the truck outside of city council chambers in a clear attempt to intimidate and surveil those seeking to hold the department accountable, and has provided no details about its decision to do so.”

Gaona was also concerned that the department did not keep a log of the equipment’s use. In response to that concern, a Phoenix Police Department Sergeant said, “Do you want us helping maintain public safety or creating administrative records?”

The LBPD’s deployment of its FOTM system at a morning peace walk raises the same issues mentioned by the ACLU of Arizona regarding the chilling effect surveillance can have on free expression. It is unclear whether the LBPD keeps a log of the FOTM use. While records related to the purchase of the camera system were turned over, a request for a log or record of the LBPD’s use of their FOTM camera has been pending since Aug. 13—without the department following the procedure for extensions, including informing the requestor why extra time to respond to the request is needed or when documents might be produced. A request for communications regarding the FOTM system is similarly delayed.

FOTM PURCHASE INFORMATION

A request for LBPD documents related to the purchase of the FOTM systems did not produce an invoice or purchase order, but instead generated a statement that read “LA Region Law Enforcement agencies who participate in the UASI Federal grant funding made a bulk purchase of the surveillance devices and distributed [to] the local agencies who funded their own vehicles to support the surveillance system. The Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department or the City of Los Angeles Mayor’s office may have purchased directly from Strongwatch.”

Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI) and Operation Stonegarden (OPSG) are a major source of funds for local law enforcement, with the federally-designated Los Angeles/Long Beach Area receiving $68 million in UASI grants in 2019. Long Beach received $6.7 million in Homeland Security grant funds in 2019, according to the City’s 2020 budget. Total Federal and State Homeland Security grants to Long Beach have averaged $9 million in recent years.

Along with the statement about the bulk purchase, the police department turned over the purchase records for the GMC Sierra 1500 Model TK15745 1/2-ton pickup truck that matches the make and model of the truck posted on Instagram by BLM LBC. The purchase was made in March 2014, with signed approval from former Police Chief Jim McDonnell, former City Manager Patrick West, and Current LBPD Patrol Bureau Deputy Chief Michael Lewis. The truck cost $39,246 with the City Manager Purchase Approval form listing that it will be used to “deploy a thermal imaging, day/night surveillance camera system … for CBRNE/Homeland Security/terrorism detections and preventions.” CBRNE stands for Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosive.

The purchase approval form notes that “time is of the essence” as the Homeland Security grant money was set to expire on March 31, 2014, and that without the purchase “the Long Beach Police Department will be less able to maximize the safety and security of the citizens attending large-scale events and critical locations like the POLB [Port of Long Beach] and the Long Beach Airport.”

The LAPD and the City of Los Angeles did not have purchase records for the FOTM cameras. A records request to the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department was filed on Aug. 17, and two weeks later the agency sent a notice that it was backlogged due to unexpected personnel shortages.

One department has released their purchase documents for the system. Phoenix police purchased a FOTM camera with Homeland Security grant money in 2012—with equipment, training, and upgrades totaling $210,000 over the last seven years, according to the Arizona Republic.

Tomisin Oluwole

Dine with Me, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Freedom Surveillance’s map of deployments, marketing material, and websites paint the picture of a company that mainly, if not only, sells to the government. Never-the-less their business must have been affected by COVID-19, as they received $150,000-350,0000 in Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) money.

Examining the list of businesses that tapped into Small Business Administrations PPP funds revealed that many well-financed surveillance technology companies with millions in active government contracts were able to receive PPP money, while small businesses nationwide are shutting down after being unable to get qualified for money from the Small Business Administration before funds ran out.

You can read more about some of the other surveillance companies contracted by the LBPD that qualified for PPP money in a sidebar to this piece, Surveillance Technology Vendors Took Coronavirus Bailout Money Meant for Small Businesses.

THERMAL CAMERAS OR FORWARD-LOOKING INFRARED CAMERAS

The FOTM camera is not the only thermal camera owned by the LBPD. The Aaron Swartz Day Police Surveillance Project requested documents from the LBPD that produced a January 2019 response revealing that the LBPD owns two Forward-Looking Infrared (FLIR) 230HD thermal cameras, one mounted on each of the LBPD’s helicopters. In response to the part of the request dealing with policy documents, the LBPD responded “there are currently no policies, training documents, or prohibited activities. After purchase, the vendor provided 6 hours of training to each pilot in the unit.”

A lack of a policy or prohibitions on the use of a camera might not seem like something worth writing about, but a FLIR is not a regular camera. In Kyllo v United States (2001) the Supreme Court held that when “the Government uses a device that is not in general public use, to explore details of the home that would previously have been unknowable without physical intrusion, the surveillance is a “search” and is presumptively unreasonable without a warrant.” Kyllo was a case dealing with federal agents using a FLIR to identify an indoor marijuana growing operation in Oregon in 1991, but it is still the controlling case on the issue of thermal cameras and is widely cited in other cases on technological searches.

The 5-4 decision—rare in that the opinion was written by Justice Antonin Scalia and joined in its entirety by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg—does not create a hard-line rule for FLIR but instead acknowledges that whatever technology is available to and in wide use by the general public will have an effect on an individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy.

Numerous constitutional scholars have pointed out that the increased sale of consumer thermal cameras and even phones capable of taking thermal images could erode the expectation of privacy one might have regarding the heat signature of their home. However, law enforcement technology—which is capable of mapping the interior of houses and tracking individuals in them—is still so far ahead of what is commonly available to the general consumer that Kyllo still requires a search warrant to use FLIR cameras and other advanced devices to examine a home absent an emergency situation that overrides the need for probable cause. FLIR cameras have applications that do not implicate the Fourth Amendment, such as finding missing people or assisting with in-progress chases—which are emergencies that overcome the warrant requirement. Thermal cameras can be used to track fleeing suspects at night and are so sensitive they can tell which parked car has recently been used by gauging residual engine heat. Outside of these sorts of situations, the use of FLIR devices can easily violate people’s constitutional rights. A situation that other cities have addressed with policies to govern the use of FLIR cameras—which contain discussions of Kyllo and the Right to Privacy, while setting out rules on allowable use, oversight, and data retention.

MOBILEYE

The FOTM camera is not the only camera to be spotted around town and talked about on social media. The department owns another vehicle they call the MobilEye, which trended on the Long Beach subreddit this week when a photo was posted that appears to show an unhoused person defecating next to the vehicle. The MobilEye is a repurposed armored SWAT van painted to stand out, including a large notice that it is an LBPD vehicle “with cameras in use.” I first learned about the MobilEye by examining the LBPD training documents and special orders posted online to comply with Senate Bill 978, but it has previously been written about in the Grunion Gazette.

The MobilEye has seven cameras (two ALPRs, four stationary cameras, and one pan/zoom camera). The MobilEye Special Order policy document has a section devoted to privacy concerns that contains the statement “the Department is aware of potential privacy concerns regarding the use of MobilEye. In order to address these concerns the MobilEye has been designed as an overt surveillance system.”

The document continues, “the MobilEye will not be used for the arbitrary viewing of citizens or for viewing activity where a reasonable expectation of privacy exists.” In the Gazette article, Deputy Chief Richard Rocchi says the communities where MobilEye is deployed “understand we are not doing surveillance on the community … It’s there to provide safety and security.” Judging by the reaction to the deployment of the FOTM system on social media, such an understanding was not reached regarding that system.

The MobilEye special order mentions its Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) capabilities multiple times. The LBPD has issued a separate special order regarding ALPR use that includes the statement that ALPR “may not be used for the purpose of monitoring individual activities protected by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.” Political protest is an activity protected by the First Amendment—which includes the right to free speech and the “right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The FOTM camera is more advanced than the MobilEye and yet there is no posted special order, training manual sections, or training document that regulate its use by the department. Under Senate Bill 978, the city is required to post all training and policy documents online and has posted an extensive collection of training and policy documents, but none related to the FOTM camera.

SURVEILLANCE EQUIPMENT TRANSPARENCY ORDINANCES

Privacy advocates have proposed many solutions to the technological slippery slope they see government agencies heading down. For instance, California recently passed a law putting in place a moratorium through 2023 on the use of facial recognition technology on the live feed from an officer’s body cameras while state lawmakers try to develop policies to address the potential for racial biases raised by the inaccuracies of the technology.

Other California cities have banned facial recognition technology completely due to its general accuracy issues and racial bias. One study showed Asian and Black people were up to 100 times more likely to be misidentified by some systems. In the real world, there have been potential wrongful convictions made using facial recognition and certain wrongful arrests due to the technology’s difficulty telling one Black man from another.

Another way to approach the problem is not to ban any technology, but to require disclosure of police use of the technology along with policies to ensure proper, constitutional use. This can be seen in California Senate Bill 34, which was signed into law in 2015 and created standards and policy requirements for ALPR use—including public disclosure and a public comment opportunity before the technology is introduced.

One all-encompassing solution was proposed in Senate Bill 21, which stalled in 2017. Had it passed, it would have required a public approval process for all local surveillance purchases and biennial transparency reports covering the cost, use, and effectiveness of the technology. However, there is no reason to wait for the state to pass a version—ten cities have passed their own local Surveillance Equipment Transparency Ordinances, including San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Davis, and Palo Alto, along with Bay Area Rapid Transit and the entire county of Santa Clara.

On an individual level, the EFF has a wealth of resources for protecting your digital privacy and the ACLU has multiple guides for protecting yourself while you exercise your First Amendment rights.

One of the most powerful tools Californians have is the California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA), which allows us to opt-out of private data collection and sales by data brokers. The law just went into effect this January and applies to any business that operates in California and has over $25 million in revenue, collects data on 50,000 consumers, or gets more than half its revenue from data sales.

The law creates a Right to Know what data is stored on you, a Right to Delete the data, and a Right to Opt-Out of the sale of your data. Many surveillance companies have CCPA compliance pages such as facial recognition company Clearview AI and the multifaceted Vigilant Solutions—both used by the LBPD. I’ve submitted requests on both companies myself. The process for Clearview AI involves sending in a picture of yourself for them to scan against their database, which is not the most comforting process. For the sake of journalism and against my better judgment I submitted my photo. My request returned the response that “after running the photo provided through our algorithm, no results were found.”

My request to Vigilant Solutions is ongoing. When I first submitted a request they only verified my name and then responded that they did not have any information on me. I responded asking how they conducted a search without my plate number, which I then supplied while renewing my request. They responded on Aug. 7 that someone from their Data Protection team would contact me shortly. That was my last contact with the company.

For other companies, the process for exercising your CCPA rights can be as simple as calling a toll-free number or emailing an address you can find on a company’s website and stating you want to exercise one or all three of the rights above. Depending on the site they may ask you questions to confirm your identity or request identification. The companies are not allowed to request more information than necessary to confirm your identity and are supposed to first try to confirm your identity using information they already have on you. Most of the major data collection sites you use like social media or your service providers will have a link at the bottom of their page for California Residents with easy to follow instructions.

What’s Next

As this series continues, it will explore a wide range of technologies and will cover the current state and local policies governing them, the costs and benefits of the technology, and their potential for misuse. Misuse is a serious concern as can be seen from previous reporting done on the LBPD’s use of Automated License Plate Readers. Besides the privacy issues created by the LBPD logging images and location data of 25 million plates per year, there have already been actual cases where innocent lives were put at risk by the LBPD’s overzealous use of the technology.

As has been first reported in Forward and followed up on locally by Stephen Downing of the Beachcomber (with a sidebar by this writer), the LBPD’s Looter Taskforce flagged the license plates of innocent protestors as involved in felony robberies. This resulted in them being terrorized at gunpoint while their cars were wrongfully impounded by police in other cities—who only saw the LBPD’s felony robbery note and acted accordingly. The LBPD made a small attempt to correct that wrong by apologizing to the women involved and reimbursing their impound fees. However, the issue of inadequate policies and oversight of police technology use remains unaddressed regarding ALPR and many of the other technologies used by the LBPD.

The next article in this series will focus on another technology from Vigilant Solutions, which in addition to the ALPR system described above also makes the facial recognition product currently in use by the LBPD. Facial recognition has a broad sense of meaning; even in police use there are a wide variety of ways the technology can be employed. Currently, the LBPD is limited on how it can use facial recognition by a state moratorium on its use on live feeds from body cameras through 2023, but once that expires there will be no other limit on its use—other than the police department’s general respect for the Constitution.

Facial recognition is not a topic that has been addressed by LBPD policy or the City Council. While numerous cities have adopted policies to make sure that this powerful technology—which still contains severe flaws that disproportionately affect racial minorities—is used responsibly, Long Beach is not one of them. Part two of The Surveillance Architecture of Long Beach will discuss what is known about the LBPD’s facial recognition program and explore the policy implications that exist now and will become much more pressing in the future as the technology advances.

Greg Buhl is a Long Beach resident and attorney. He took up writing as a hobby during the COVID-19 lockdown and with more reasons than ever to not go outside he’s going to be tackling some ambitious writing projects.

Questions, comments, concerns, or tips can be directed to him at his relatively new twitter @legalshepherd or securely to GregBuhl@protonmail.com.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Feel free to distribute, remix, adapt, or build upon this work.

![]()

legalshepherd562@gmail.com

legalshepherd562@gmail.com