The Compliance Business: Long Beach Considers Adult-Use Cannabis Ordinance

Some are Pleased, Some Not so Much

14 minute readLegal sales of recreational cannabis in Long Beach could begin as early as August 2018. Last month, the Long Beach City Council voted to advance an adult-use ordinance after its first public hearing. On Tuesday, a second vote will take place and, if passed (which is expected), the ordinance will be formally implemented.

The first vote was 7-1 in favor, with Councilmember Stacy Mungo being the lone dissenter.

“Everyone has to pass it tonight,” Mungo remarked, showing frustration. “I’ve heard that at least 40 times in a week.”

She wanted more time to work on the language of the ordinance, possibly placing guarantees that dispensaries hire residents of the districts that the dispensaries are operating in.

“My goal would be that we have adult-use available in the city September 1st,” she said.

Currently, only medical marijuana sales are legal in the city of Long Beach. In order to make a purchase, a customer must have a letter of recommendation from a doctor advising that they would benefit from medicinal cannabis.

Stefan Borst-Censullo is an activist and attorney who represents cannabis businesses in Long Beach. He has also been a city-registered lobbyist for various cannabis businesses since 2015.

“I’m known to be one of the more critical people of the city in general but this ordinance appears to be pretty well-crafted. I was happy to see it pass,” he said. “It’s a far cry from even a couple of years ago. You can really see the progress on this issue.”

Recreational cannabis will be available to all those 21 years or older. Pot shops will be allowed to stay open until 9 p.m. and delivery services can operate until 10 p.m.

Adam Hijazi, co-owner of the Long Beach Green Room, a local dispensary, and a founding member of the Long Beach Collective Association, a trade association consisting of cannabis business owners, was pleased with the vote.

He has some concerns about the ordinance—including a provision that gives the city access to financial records and security footage without a warrant or notice—but ultimately believes that this is a needed step forward.

Hijazi says that the current medical-only policy is creating a nuisance, claiming street dealers often loiter outside of his shop, eager to pick up on customers he is forced turn away because they don’t have a letter of recommendation from a doctor.

He thinks that once cannabis sales become more normalized in the city, regulations will ease up.

“We’re not moving nuclear waste from one place to another. But that’s how it’s being treated,” he said.

Zoning Out

The ordinance will add a designation in the zoning code for adult-use cannabis businesses, which will track with similar businesses depending on their type. For instance, dispensaries will be allowed to locate in commercial areas and cultivators and manufacturers will be allowed to locate in industrial areas. Existing medical marijuana businesses will be allowed 180 days to apply for adult-use licenses regardless of new zoning restrictions.

Buffer zones that restrict adult-use cannabis businesses from operating in certain parts of the city will be the same as those currently being enforced for medical marijuana businesses. Cannabis businesses cannot operate within a 1,000 feet of the beach or a school. They also cannot operate within 600 feet of a library, park, or daycare center.

State law also prohibits cannabis businesses from placing billboards within 1,000 feet of schools, daycare centers, playgrounds, and youth centers. The city’s ordinance removes youth centers and playgrounds from the list but adds public parks.

Businesses will be required to obtain a health permit from the city’s Health and Human Services Department before beginning operation. They will also be required to attend training offered by the department, which will cover topics such as prevention of underage use, risks of driving under the influence of cannabis, and safe storage methods.

The Other Kind of Green

The proposed ordinance will levy an eight percent tax on all recreational sales, which will be in addition to the state-imposed tax cultivators are charged on each ounce of marijuana buds produced. Cannabis purchasers face a state-imposed 15 percent state tax on cannabis purchases on top of the normal sales tax, which in Long Beach is 10.25 percent.

Staff predicts an increase of about $4.5 million in revenue from cannabis sales for the 2019 fiscal year.

But the city’s Cannabis Program Manager, Ajay Kolluri, cautioned the council to not count their chickens before they’ve hatched. With the state’s revenue expectations for cannabis falling short, staff warned the council that the city might also see less than expected revenue.

“Cannabis tax revenues are incredibly difficult to predict,” Kolluri said.

It’s nearly assured that the new regulatory costs of cannabis sales will result in a net loss for the city in the 2018 fiscal year, he said, and new fees may be proposed to offset these costs in the future.

“For next fiscal year (2019) we’re expecting to break even,” he said.

Additionally, medical sales in Long Beach are producing significantly less revenue in 2018 than was expected. The city predicted it would rake in about $5.2 million in new revenue but, according to the staff report, is expecting less than half that by the end of the 2018. This partly has to do with a slower rate of business creation and licensing than originally anticipated. It is also likely a result of cannabis consumers not being able to purchase in Long Beach without a medical card while there are nearby options where only an I.D. is required.

“The city’s not making the tax money and the legal dispensaries are not able to compete,” Hijazi said of the current situation.

Currently, adult-use dispensaries are allowed to operate in the cities of Santa Ana and Bellflower.

Equity Hire

The Equity Hire program is an element in the proposed ordinance that seeks to mitigate and recompense the ravaging effects that the war on drugs has had on low-income communities and communities of color, which have experienced the highest rates of low-level arrests for possession and use of marijuana.

First developed in Oakland (though they’ve been hitting a snag as of late), the program offers both mandates and incentives with the goal of hiring from low-income communities, as well as individuals who have marijuana convictions on their backgrounds. These convictions often prevent them from gaining employment in other fields.

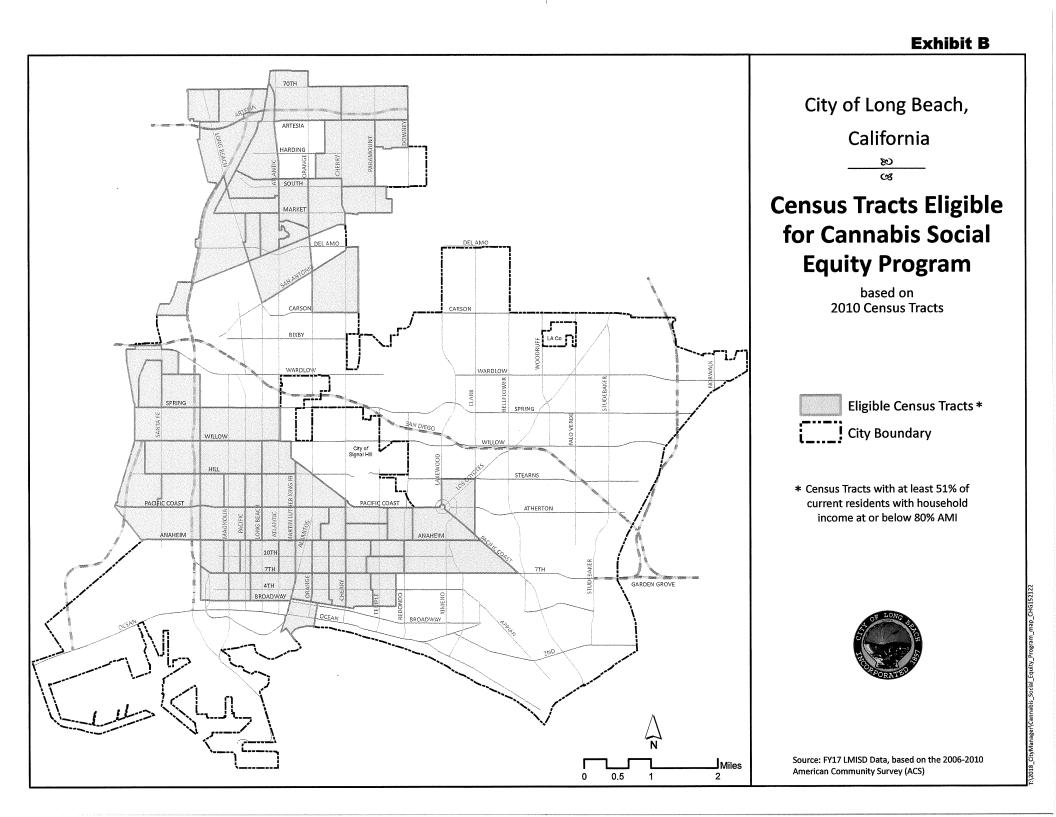

Long Beach’s program was devised by the Offices of Equity and the Office of Cannabis Management. To qualify, an individual must come from a family whose annual income is less than 80 percent of the median income in the area, have a net worth below $250,000, and have either a marijuana conviction in Long Beach before Nov. 8, 2016 that under current law would be considered a misdemeanor or infraction. If a person doesn’t have a weed conviction, they can still qualify if they’ve lived in a census tract for the past three years where at least 51 percent of the population lives at 80 percent or below of the area median income. Below is a map that shows which areas qualify:

An amendment was attached to the ordinance that would require cannabis businesses to guarantee that 40 percent of work hours are performed by individuals who meet these criteria. A “good faith” effort to meet this requirement must be proved by employers, otherwise warning and citations may be handed out by the city. If an employer can prove that there are insufficient numbers of people in their labor pool that meet this criteria, delays and lessening of requirements may be issued.

For those who meet the criteria and want to start their own cannabis business (other than a storefront, which has been capped), fee waivers, tax deferrals, expedited plan checks, application reviews, and application workshops will be offered.

Tomisin Oluwole

Dine with Me, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

The Equity Hire fee is expected to be around $2,000 per cannabis business and will help pay for the initial cost of the program, which will be $266,000. The program will be administered by Pacific Gateway, an employment agency already contracted by the city for other workforce services.

Peace, Labor, and Understanding

Continuing a standard already put in place by the medical marijuana ordinance, all cannabis businesses will be required to sign a labor peace agreement upon approval of their application. The agreement prohibits cannabis businesses from interfering in employees unionizing. Matt Bell, Executive Vice President of UFCW Local 324, which represents a little over 100 cannabis employees in Long Beach, spoke at the city council meeting two weeks ago before the vote.

“[Around] 70 percent of the people that go into the dispensaries today think it’s recreational and therefore leave [when they discover it is only medical]. And so, without passing this tonight, it really is a death sentence for these businesses and for good union jobs in the city,” Bell said. “Some of these young folks in these shops have actually turned to us and said, ‘I’m so excited, I can go home and I have the same benefits [as other union workers]. I have a great living wage. I can tell my parents. I can move out. I can have insurance. I have a pension. I have all the things that a good job requires.'”

Attorney Borst-Censullo says that the UFCW was instrumental in getting adult-use passed in Long Beach.

“There would be no legal weed in this city without UFCW. UFCW kept this issue alive when no one thought the advocates had a chance in hell.”

First Come, First Delivered?

While licensed cannabis businesses are enthused about their new customer base, some feel excluded, even going so far as to say that the city has given a monopoly to the companies already established in Long Beach.

This sentiment stems from a controversial aspect of the new ordinance, which states that in order to open a recreational cannabis shop, a business must co-locate with an existing medical cannabis business. This means that all recreational shops will be owned by medical dispensaries.

Measure MM is the Long Beach voter initiative that removed a city council ban on medical marijuana sales. It passed in 2016—the same day a statewide proposition passed legalizing recreational use—and was drafted by the Long Beach Collective Association (which some feel is a form of regulatory capture). It limits the number of medical cannabis dispensaries that can operate in the city to 32. No new recreational shops will be created unless the city decides to alter the ordinance and allow recreational shops to open without also being licensed medical shops.

The cap on cannabis licenses only applies to retail shops. New cultivation grows and manufacturers will be allowed to open in Long Beach after their application has been approved.

Still, Kolluri said “dozens” of unlicensed delivery services are currently operating in Long Beach, a claim supported by the number of listings for delivery services on Weedmaps, an app used by consumers to find nearby pot shops and other services.

John (who asked not to be identified by his real name) has owned one such unlicensed delivery service that has operated in the city for five years and says that he would have greatly appreciated a pathway to go legitimate. None of the licensed medical storefronts currently have delivery services registered with the city.

Kolluri gives more background: “[Measure MM] allows for storefront dispensaries to deliver, so a delivery service would have needed to go through that process. They didn’t actually have to operate in the storefront, they could have chosen to be delivery only, but because the medical initiative had a hard cap of 32, and the city as well as the state considers delivery services to be dispensaries, they fall under that cap of 32.”

John believes that a small group of businesses have successfully lobbied the city to give them exclusive control over an extremely lucrative and expanding industry and that the promises that small businesses would get new opportunities is not being honored by this ordinance.

“It’s windfall [for existing medical businesses], they’re the only only ones who are legally going to be allowed to make money,” he said. “I would, right now, go down to city [hall], get licensed, and start paying taxes. But they’re not even giving us the opportunity.”

In order to have even entered the medical license lottery—its first round was held in 2010, and a second in 2016—dispensary owners had to pony up a $14,742 non-refundable permit application fee to the city. Winners are charged an additional $10,000 annual permit fee, a high price to go legit for those with less access to large sums of startup capital.

Borst-Censullo, who represents businesses in the Long Beach Collective Association, believes that licensed businesses are being rightfully rewarded for years of stakeholding in Long Beach while uncertainty loomed over whether the city would ever get behind legalizing recreational cannabis. He also notes that a delivery service operating in Long Beach is doing so illegally, and to criticize the new ordinance without ever having demonstrated a willingness to comply with existing law is hypocritical.

“[The ordinance] is specifically designed to exclude people that have no interest in complying with the law. People who have been holding on to property for 4 to 5 years, paying rent on it, with no income in order to establish the good faith with the city and get the medical license process going … This wasn’t a smoke-filled back-room deal,” said Borst-Censullo. “This was brought out transparently for years.”

He also stresses that the 32 cap was approved by voters through Measure MM.

“Thirty-two businesses for the size of the city we’re in… that’s pretty diverse,” Borst-Censullo argues. “I can understand [illegal operators’] frustrations, but they would be better suited to try and open up in a new area. Long Beach is not the [only option].”

Sacramento, which has a similar population to Long Beach, currently has 30 cannabis dispensaries operating, 28 of which can sell both medical and recreational cannabis.

Another comparable city, Oakland, has 16 permitted dispensaries. Its ordinance restricts the number of dispensary permits issued to eight a year, but this cap does not apply to delivery services.

While the Long Beach dispensary cap is similar to what other cities have imposed, it pales in comparison to the 338 active liquor licenses for off-premise consumption issued in the city, according to the most recent data from the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control.

Fears that the cannabis industry in Long Beach could eventually be monopolized by a few large companies are exacerbated by the fact that licenses can be easily sold and transferred among businesses.

“There’s not really an administrative process. As far as we’re concerned, it’s a change of ownership process,” Kolluri explains. “They would have to complete a form with the city. We would need to run background checks on the new owners.”

A new cannabis license application would not be necessary and the new business owners could continue to operate while the city processes the change of ownership.

Currently, Show Grow, a cannabis company with dispensaries in Orange County and Las Vegas, owns six of the 32 licenses, according to Kolluri. Is it possible that one or two businesses will buy all the cannabis licenses in the city a few years down the line?

“Hypothetically, yes that’s possible,” said Kolluri.

Greg Gammet, the Chief Cannabis Officer for GF Distribution LLC, a business that won their licence in 2016 and will be opening a dispensary on Seventh Street and Pacific Coast Highway in the coming months, says he’s a firm believer in playing by the book but also sympathizes with illegal operators.

“I’ve been in the cannabis business a long time. I was that guy,” Gammet said, referring to those operating in the shadows. “I feel for them. I don’t want to say anything bad about [illegal operators] because the industry is built on the backs of guys like them and I respect them tremendously. At the same time there’s a set of rules and regulations.”

Gammet does have one idea for illegal operators looking to get licensed:

“I encourage them, especially if they’re on the up and up, to reach out to businesses like me and see if somehow we can bring them on for being our delivery service when we’re up and running.”

He has a counter-intuitive description of his industry: “We’re not in the marijuana business, we’re in the compliance business.”

If you appreciate journalism that doesn’t require a conflict of interest disclaimer, please consider supporting local grassroots media by subscribing to FORTHE.

joe@forthe.org

joe@forthe.org