Unhoused Long Beach | ‘Home Sweet Home, For Now’

by Kevin Flores | Published August 13, 2019 in Journalism

20 minute readUnhoused Long Beach is a series of conversations on homelessness with city officials, folks experiencing homelessness, service providers, advocates, and experts. Our hope is that by the end of the series, we’ve gathered a collection of facts and perspectives that helps readers better understand a complex, urgent, and sometimes polarizing issue that our city—and state—currently faces. In this second installment of the series we spoke to Sharon Tate and Stacy Schneider, who have been living in a motel since being displaced in March. Find part one of Unhoused Long Beach here.

For the last five months, Sharon Tate and Stacy Schneider, both 52 and disabled, have been homeless. In March, they were evicted from their downtown apartment because the owner wanted to build an upmarket residential project on the property. Since then, they’ve mostly been staying at the Colonial Pool and Spa Motel, waiting for a subsidized apartment to become available through the city’s Rapid Rehousing program.

The motel is a ratty spot on Pacific Coast Highway—its one-star Yelp page is filled with ghastly reviews—but it offers some of the cheapest rates in town. Code enforcement officers have actually cited the motel for bed bugs and roaches in the past. Even so, the roommates say it’s better than sleeping outside—“Home sweet home, for now,” Schneider quips.

Apart from the occasional misguided out-of-towner, motels like this largely serve as a refuge for those on the brink of destitution. Many of them can be found clustered along a stretch of PCH that runs through the Washington and Poly High neighborhoods, about a 30-minute walk from the Long Beach Multi-Service Center, where unhoused folks have access to social workers, showers, three meals a day, and a variety of other services.

In a previous installment of this series, Daniel Brezenoff, the mayor’s senior advisor on homelessness and housing, talked about a state senate bill introduced in February that would make it easier for motels like the Colonial to be converted into fully-fledged transitional housing.

The saga of how Tate and Schneider ended up at one of these motels began over two years ago.

The parcel that contained the near-century-old building where the roommates had lived for 14 years was bought in 2017 by Leeward Capital of Long Beach, a Delaware-based limited liability company.

Soon after the company took over the 1101-1157 Long Beach Blvd. property, it sent a change of ownership notice to tenants saying “…we look forward to a long relationship together.”

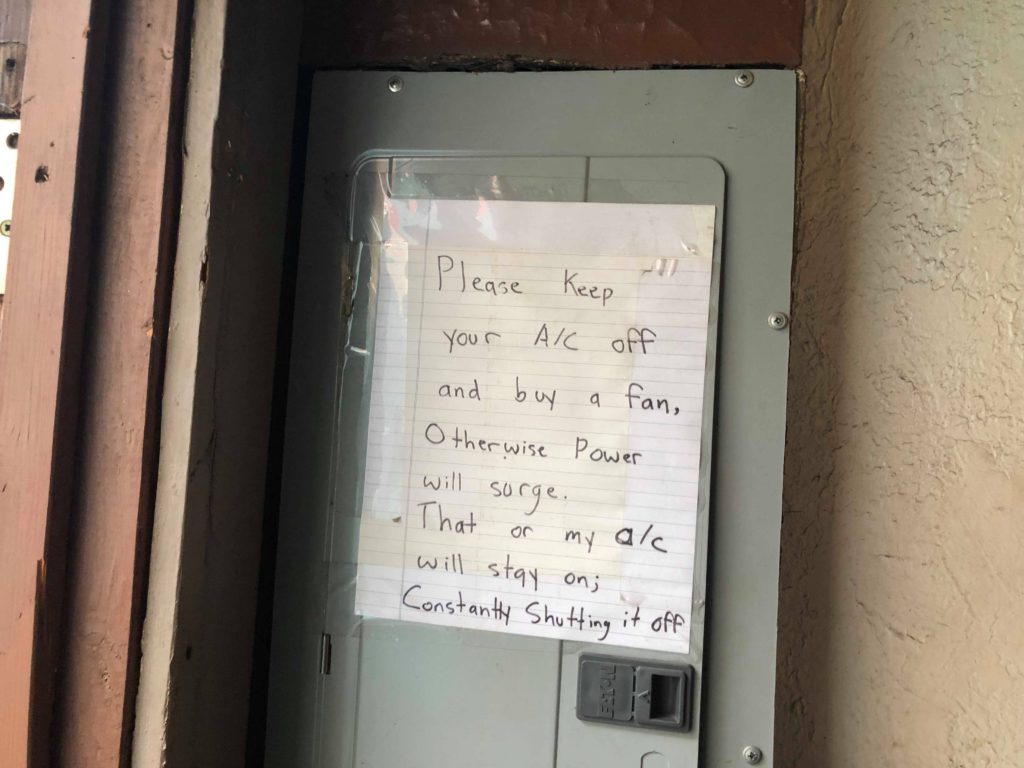

But that relationship soured quickly, the women say, because the new owner neglected the building while still collecting rent. Mold, vermin infestations, unsafe stairs, and a dysfunctional electrical system were among the many problems plaguing the structure.

In late 2017, code enforcement inspectors noted 18 violations at the address. The violations went uncorrected after five re-inspections over four months, city records show. A lien was eventually placed on the property for failure to pay the $2,395 in fines and fees levied by the city. In the meantime, Leeward Capital did find the money to contribute $800 to Mayor Robert Garcia’s 2018 reelection campaign.

Inspectors tagged the building with more violations on June 2018, saying that the structure showed evidence of “rot, infestation and progressive deterioration.” Again the landlord seemingly ignored the violations and subsequent citations, prompting code enforcement to file another lien on the property for the outstanding balance, this time totaling more than $9,000.

The managing member of Leeward Capital is Barry Beitler, who also happens to be a managing partner at Pacific Property Partners, the firm developing the site. Beitler did not return multiple requests seeking comment. Los Angeles County Assessor records show that he owns a $3.7 million mansion in Brentwood.

Tomisin Oluwole

Coquette

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 24 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Amidst the piling up code violations, the Planning Commission in September approved a site plan submitted by the developer for a 120-unit, mixed-use project at the location. It called for the demolition of the so-called Plaza Hotel building where Schneider, Tate, and nearly two dozen other low-income tenants lived. There was no mention of these tenants at the meeting.

By this point, the last hangers-on in the building, including Schneider and Tate, had stopped paying rent because they had been dealt unlawful detainer lawsuits, yet were unable to find another home.

The Plaza Hotel, which had previously been the Astor Hotel and then the Al Mar Hotel—which, rumor held, once housed convalescing soldiers injured in WWII—was something of a holdover from the days when single-room occupancy housing was commonplace downtown.

In more recent times the location had become a hotspot for police activity, its facade often scrawled with graffiti, and it even had a problem with squatters occasionally wandering in off the street—yet, it was an affordable home to disabled folks, low-income families, and seniors.

With help from a letter sent by the city prosecutor threatening anyone still inside with a misdemeanor trespassing charge, the last remaining residents were cleared out of the building by March and it was bulldozed a few months later.

A relocation assistance law that has been on the city’s books since 1991 says that property owners must give low-income renters who will be displaced by a demolition an 18-months notice and provide them with relocation assistance. It explicitly states that a landlord cannot evict renters using the traditional 30/60-day notice to quit to get around these requirements. However, former tenants who were evicted from the Plaza Hotel building say these rules were not followed. The law is administered by the Housing and Neighborhood Services Bureau. A Development Services spokesperson said that the bureau never received information indicating that there were any legal occupants in the building when the owner applied for a demolition permit.

The site is now being prepared for construction and the project that will soon lord over that corner is part of Pacific Property Partners recent forays into the burgeoning downtown area. They are also in the process of renovating the 13-story Security Pacific National Bank on Pine Avenue into a 210-room hotel, and earlier this year the builder joined a cadre of business interests in signing an open letter in support of constructing a baseball stadium on the downtown waterfront.

For their part, Schneider and Tate are among 21 former tenants displaced from the Plaza Hotel who are listed as plaintiffs in a civil lawsuit against Leeward Capital seeking damages caused by the owner’s alleged failure to maintain the building in a habitable condition in the two years before it was knocked down.

“I think it’s pretty clear that the owner has been wanting to [demolish the building] for years, perhaps. And ever since that determination was made, they pretty much neglected it as owners,” said Christofer Chapman, the attorney representing the tenants. “For the most part, these tenants are poor people who really have no place to go. They have little resources, they have medical problems, some have mental illnesses.”

We caught up with Schneider and Tate at the Colonial Motel in July to ask them about their experience with displacement and homelessness thus far.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Update: On Monday, Schneider said she and Tate were no longer receiving vouchers from the city to pay for their room at the Colonial motel. “Don’t know where we will be next week,” she said.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

kevin@forthe.org

kevin@forthe.org @reporterkflores

@reporterkflores