OK, NIMBY: Some thoughts on the class contradictions of the single-family home-‘owner’

by James Andrew Carroll | Published November 19, 2019 in Perspectives

32 minute readFrom the Editors: What follows is a personal perspective of the author, and not an official position of FORTHE Media.

Introduction

The following essay is a collection of thoughts I have been struggling with over the past few months, touching on a variety of related subjects: from ongoing civic debates over the new bike lanes down Broadway and the city’s Land Use Element; to known political actors like Robert Fox and the class of single-family home-“owners” he has claimed to be the voice of; to more abstract concepts like capitalism, ideology, and rent.

The tone of the essay ranges from angry to invitational. The angry bits may distract you from the invitational bits, but they each serve a role. The anger—aside from its therapeutic benefits—is meant to open up space for criticism of a powerful class that tends to dominate discourse in our city; and the invitation—despite my frustrations—is meant to create opportunities for understanding and collaboration across class boundaries. Some members of the targeted class may not get past the anger to the invitation, but that is less of a priority for me than expressing what I feel has not yet been said in the pages of a Long Beach publication, and doing so in solidarity with those voices who, to a lesser or greater extent, already feel these truths.

The language in this essay mainly consists of dialectical analysis. The dialectic is a form of critique that seeks to illuminate the contradictions in various concepts, at an abstract level, in order to better explore what is happening more concretely beneath them. A simple example of dialectical analysis is to take the concept, “a dollar bill”, and make the observation that “a dollar bill” in 1930 is different from “a dollar bill” in 2019; or that “a dollar bill” in a savings account is different from “a dollar bill” in the hand of someone about to make a purchase; or that “a dollar bill” in California is different from “a dollar bill” in Wisconsin. The concept, “a dollar bill”, contains all these contradictions. This doesn’t mean “a dollar bill” is nonsense and has no purpose in language; it just means that, depending on the aim of our discourse, the concept may be masking another meaning, and we may wish to uncover it. [1] (All footnotes can be clicked for a pop-up with further reading.)

Having said all that, abstraction is intrinsic to language, and throughout the text I refer to single-family home-“owners” in a general way—so it should be understood beforehand that while generalizing allows us to analyse various phenomena at a certain level, it does so by ignoring anecdotal counter-examples. (This also has its uses.) Thus, let me preempt by saying: no, it doesn’t matter that you know a nice single-family home-“owner” who displays none of the politics I am going to discuss and is happy to have low-income, multi-family housing built in their neighborhood (such as my mom or my dad or my grandpa). What matters is that there are single-family neighborhood advocates all over this country—and this city—who have the privileges of time, wealth, age, and race on their side, and who consistently say awful or ignorant things about density while fighting to maintain the status quo of our unjust economic system. These folks need to be opposed in a public and unequivocal way. That is the primary purpose of this essay.

In lieu of proper transitions, I have elected to separate the thoughts into various sections to highlight their disparate but connected qualities. Some sections, for instance, are basically long asides. Their titles are, at times, a bit silly, and this is to compensate for the essay itself being a bit too literal. Robert Fox claims he gave up a nice retirement in Honolulu to run for office because he had to. Well, I gave up irony in order to expose the bullshit of home-“owner” politics because I had to. I just hope the reader appreciates which of our sacrifices is greater.

Finally: the essay’s style may provoke more than it explains—but, regardless, I hope it is still cohesive enough to encourage thought; and of course I welcome all questions, disagreements, and expressions of solidarity. I have listed various ways you can contact me at the bottom of this essay, and I look forward to new conversations.

From the Editors: What follows is a personal perspective of the author, and not an official position of FORTHE Media.

Introduction

The following essay is a collection of thoughts I have been struggling with over the past few months, touching on a variety of related subjects: from ongoing civic debates over the new bike lanes down Broadway and the city’s Land Use Element; to known political actors like Robert Fox and the class of single-family home-“owners” he has claimed to be the voice of; to more abstract concepts like capitalism, ideology, and rent.

The tone of the essay ranges from angry to invitational. The angry bits may distract you from the invitational bits, but they each serve a role. The anger—aside from its therapeutic benefits—is meant to open up space for criticism of a powerful class that tends to dominate discourse in our city; and the invitation—despite my frustrations—is meant to create opportunities for understanding and collaboration across class boundaries. Some members of the targeted class may not get past the anger to the invitation, but that is less of a priority for me than expressing what I feel has not yet been said in the pages of a Long Beach publication, and doing so in solidarity with those voices who, to a lesser or greater extent, already feel these truths.

The language in this essay mainly consists of dialectical analysis. The dialectic is a form of critique that seeks to illuminate the contradictions in various concepts, at an abstract level, in order to better explore what is happening more concretely beneath them. A simple example of dialectical analysis is to take the concept, “a dollar bill”, and make the observation that “a dollar bill” in 1930 is different from “a dollar bill” in 2019; or that “a dollar bill” in a savings account is different from “a dollar bill” in the hand of someone about to make a purchase; or that “a dollar bill” in California is different from “a dollar bill” in Wisconsin. The concept, “a dollar bill”, contains all these contradictions. This doesn’t mean “a dollar bill” is nonsense and has no purpose in language; it just means that, depending on the aim of our discourse, the concept may be masking another meaning, and we may wish to uncover it. [1] (All footnotes can be clicked for a pop-up with further reading.)

Having said all that, abstraction is intrinsic to language, and throughout the text I refer to single-family home-“owners” in a general way—so it should be understood beforehand that while generalizing allows us to analyse various phenomena at a certain level, it does so by ignoring anecdotal counter-examples. (This also has its uses.) Thus, let me preempt by saying: no, it doesn’t matter that you know a nice single-family home-“owner” who displays none of the politics I am going to discuss and is happy to have low-income, multi-family housing built in their neighborhood (such as my mom or my dad or my grandpa). What matters is that there are single-family neighborhood advocates all over this country—and this city—who have the privileges of time, wealth, age, and race on their side, and who consistently say awful or ignorant things about density while fighting to maintain the status quo of our unjust economic system. These folks need to be opposed in a public and unequivocal way. That is the primary purpose of this essay.

In lieu of proper transitions, I have elected to separate the thoughts into various sections to highlight their disparate but connected qualities. Some sections, for instance, are basically long asides. Their titles are, at times, a bit silly, and this is to compensate for the essay itself being a bit too literal. Robert Fox claims he gave up a nice retirement in Honolulu to run for office because he had to. Well, I gave up irony in order to expose the bullshit of home-“owner” politics because I had to. I just hope the reader appreciates which of our sacrifices is greater.

Finally: the essay’s style may provoke more than it explains—but, regardless, I hope it is still cohesive enough to encourage thought; and of course I welcome all questions, disagreements, and expressions of solidarity. I have listed various ways you can contact me at the bottom of this essay, and I look forward to new conversations.

I.

The Fox and the LUE

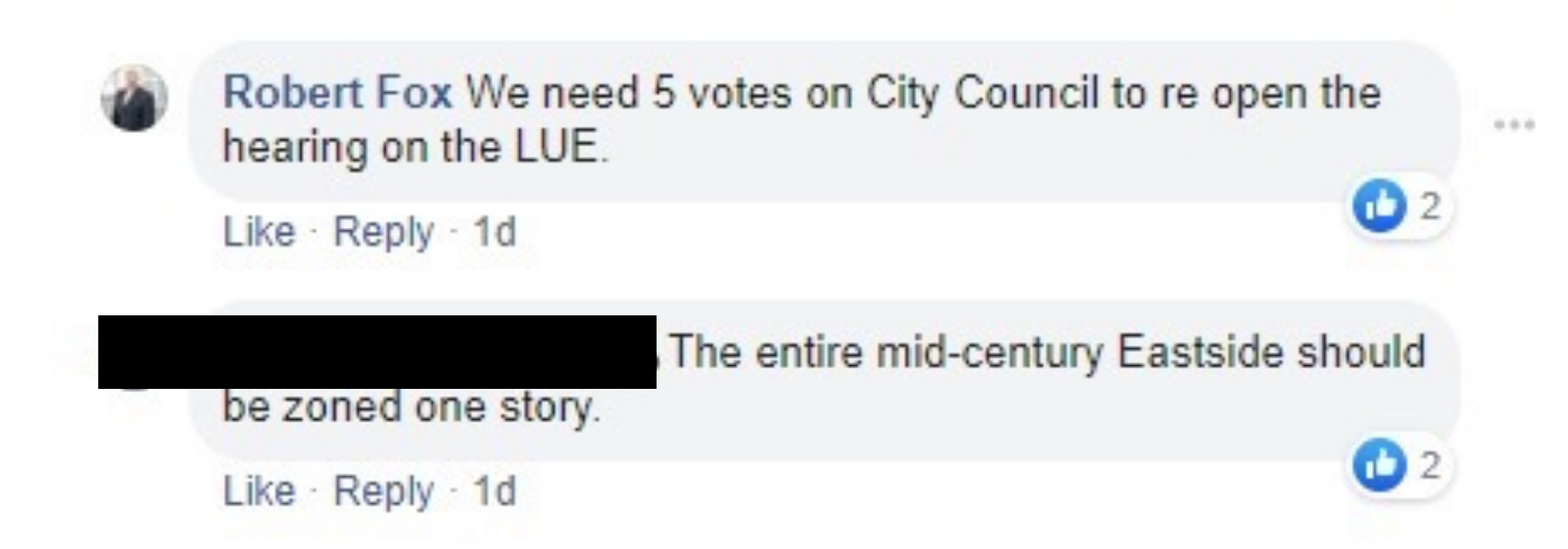

Before Robert Fox, a candidate for Long Beach’s 2nd City Council District, was rallying single-family home-“owners” [2] against the sheer bureaucratic audacity and corruption of bike lanes, he was the most vocal leader against the overhaul of Long Beach’s Land Use Element.

The Land Use Element (LUE) is a map the city is mandated to create, and it defines, or rather suggests, changes to local zoning. It does not approve any developments; nor does it force property-owners to do anything. It merely serves as a guide for city planners as part of a long-term vision for potential future development. The city had not previously updated the map for over 30 years—meaning they were a bit overdue.

For a detailed discussion of the frustrating process that ended in the LUE’s passage by our City Council in March 2018, you can read a piece I wrote at its culmination. For the moment, however, I want to agree with Fox concerning his present insistence that the drafting of the LUE be reopened—and of course I want to agree for all the completely opposite reasons. In Fox’s fever dream of a politics, he is a knight-like defender of a particular tradition of representative government, where democracy is envisioned as an ongoing series of arguments that property-owners have amongst themselves about how to resolve disputes over the boundaries of their competing interests. In other words, he partly embodies the contradictions of the American Revolution: he envisions himself to be a soldier against a deaf autocracy, yet clearly he is himself a member of a very privileged class, for whose interests his “revolution” begins and ends.

In Fox’s fever dream of a politics, he is a knight-like defender of a particular tradition of representative government, where democracy is envisioned as an ongoing series of arguments that property-owners have amongst themselves about how to resolve disputes over the boundaries of their competing interests. In other words, he partly embodies the contradictions of the American Revolution: he envisions himself to be a soldier against a deaf autocracy, yet clearly he is himself a member of a very privileged class, for whose interests his “revolution” begins and ends.

Fox thus believes the Long Beach LUE was a complete affront to his class of single-family home-“owners.” Why does he believe this? Because the original update to the LUE prepared by the city dared to suggest that over the course of the next two decades Long Beach should expand its zoned capacity to meet its growing population needs.

Most of this increase in zoned capacity was modest, and was suggested to take place mainly in areas surrounding high-traffic, transit-oriented corridors. But over the course of the year-long struggle to pass it, Fox and his friends successfully altered the map again and again, shrinking the suggestions until, at last, they managed to reverse a fair amount of them: the final, approved LUE map—believe it or not—proposed that certain zoning capacities reserve even more space for single-family homes.

It should be stressed here that the only reason the city was mandated to update the LUE to begin with is because the city is also mandated by the state to do its part in accommodating California’s growing population. The politics of the anti-LUE crowd is so backwards, that a map with the sole purpose of planning for more residents managed instead to shrink the city’s future capacity to house people.

Despite such a clear victory, however, Fox is not satisfied. If the LUE is indeed reopened, he would seek to further limit opportunities to live here.

I.

The Fox and the LUE

Before Robert Fox, a candidate for Long Beach’s 2nd City Council District, was rallying single-family home-“owners” [2] against the sheer bureaucratic audacity and corruption of bike lanes, he was the most vocal leader against the overhaul of Long Beach’s Land Use Element.

The Land Use Element (LUE) is a map the city is mandated to create, and it defines, or rather suggests, changes to local zoning. It does not approve any developments; nor does it force property-owners to do anything. It merely serves as a guide for city planners as part of a long-term vision for potential future development. The city had not previously updated the map for over 30 years—meaning they were a bit overdue.

For a detailed discussion of the frustrating process that ended in the LUE’s passage by our City Council in March 2018, you can read a piece I wrote at its culmination. For the moment, however, I want to agree with Fox concerning his present insistence that the drafting of the LUE be reopened—and of course I want to agree for all the completely opposite reasons.

In Fox’s fever dream of a politics, he is a knight-like defender of a particular tradition of representative government, where democracy is envisioned as an ongoing series of arguments that property-owners have amongst themselves about how to resolve disputes over the boundaries of their competing interests. In other words, he partly embodies the contradictions of the American Revolution: he envisions himself to be a soldier against a deaf autocracy, yet clearly he is himself a member of a very privileged class, for whose interests his “revolution” begins and ends.

In Fox’s fever dream of a politics, he is a knight-like defender of a particular tradition of representative government, where democracy is envisioned as an ongoing series of arguments that property-owners have amongst themselves about how to resolve disputes over the boundaries of their competing interests. In other words, he partly embodies the contradictions of the American Revolution: he envisions himself to be a soldier against a deaf autocracy, yet clearly he is himself a member of a very privileged class, for whose interests his “revolution” begins and ends.

Fox thus believes the Long Beach LUE was a complete affront to his class of single-family home-“owners.” Why does he believe this? Because the original update to the LUE prepared by the city dared to suggest that over the course of the next two decades Long Beach should expand its zoned capacity to meet its growing population needs.

Most of this increase in zoned capacity was modest, and was suggested to take place mainly in areas surrounding high-traffic, transit-oriented corridors. But over the course of the year-long struggle to pass it, Fox and his friends successfully altered the map again and again, shrinking the suggestions until, at last, they managed to reverse a fair amount of them: the final, approved LUE map—believe it or not—proposed that certain zoning capacities reserve even more space for single-family homes.

It should be stressed here that the only reason the city was mandated to update the LUE to begin with is because the city is also mandated by the state to do its part in accommodating California’s growing population. The politics of the anti-LUE crowd is so backwards, that a map with the sole purpose of planning for more residents managed instead to shrink the city’s future capacity to house people.

Despite such a clear victory, however, Fox is not satisfied. If the LUE is indeed reopened, he would seek to further limit opportunities to live here.

II.

Is Long Beach a Progressive City?

Fox and the city government have fashioned themselves into enemies of sorts—a relationship that seems useful to both: Fox gets to fight The Powers That Be while also clearly benefiting from the economic status quo, and the Mayor gets to pretend that the city could build a lot more affordable housing if it weren’t for the NIMBYs. Within this ongoing stand-off, criticizing one side could appear like defending the other. To avoid any confusion, therefore, I would like to spend this section directly criticizing the city government and its leadership before I continue with Fox and the NIMBYs.

During the recent California Democrats conference Downtown, Mayor Robert Garcia said Long Beach was much more conservative 10 years ago than it is now, and claimed, “Today, this city is leading the way on… economic justice…”

Ah! The sort of vague boast that one would only ever attempt in the safety of a political rally, where, with the mundanity of a period, every sentence is punctuated with roaring applause. I’m sure we are all thrilled to know that Long Beach has finally been deemed progressive enough to host a CADEM conference; but then perhaps our elected officials should also have the humility to realize that they are following California’s lead—not the other way around.

To me, any city that continuously rolls over to whichever interest happens to be the most monied and organized and privileged at the time, cannot call itself a leader on much of anything, let alone economic justice. Yet the City of Long Beach did roll over, and over, and over for nearly a decade while the Downtown Plan displaced many of our residents; and then the City of Long Beach rolled over, and over, and over again for one full year while the Land Use Element was shredded piece-by-piece in the interests of property-“owners.” Is that “leading the way”?

Leadership cannot mean passing, as the City Council did in May of this year, a modest tenant relocation assistance ordinance—and doing so for some strange reason without making it retroactive to the date of its passage, or at least including a moratorium to prevent evictions until it took effect—almost one full decade after the Downtown Plan was passed, and after thousands of residents had already been displaced.

Leadership cannot mean passing, several months later in November, a very brief moratorium on no-cause evictions after the state government effectively cornered cities to do so by passing state-wide renter protections (AB 1482). Keep in mind that just a few years ago, when housing activists wanted to pass Just Cause Eviction protections (a humble request compared to rent stabilization), the conversation couldn’t even get out of the Human Relations Commission because our local class of locusts—the landlords [3]—swarmed over the narrative and consumed it until there was nothing left.

So, yes, the City Council recently passed a moratorium on no-cause evictions; but it also risked almost nothing in doing so—as evidenced by the lack of landlord testimony during the meeting, by the number of cities that accomplished this before Long Beach, and by the council’s unanimous vote. [4] It is pure cynicism to bow to developers when they’re the most powerful (the Downtown Plan), and then bow to landlords when they’re the most powerful (Just Cause Eviction), and then bow to single-family home-“owners” when they’re the most powerful (the LUE), and then bow to the state government when it’s the most powerful (AB 1482). That is not leadership! That’s crawling with your head down through the trenches of other peoples’ struggle.

You can still walk through the neighborhoods surrounding Cesar Chavez Park and Drake Park and see whole multi-family units gutted. Why didn’t they get to stay home for the holidays? Where is the reckoning for those who have stolen this city from so many working-class families? Where are the apologies? Where is the restitution? Where is the “economic justice”?

II.

Is Long Beach a Progressive City?

Fox and the city government have fashioned themselves into enemies of sorts—a relationship that seems useful to both: Fox gets to fight The Powers That Be while also clearly benefiting from the economic status quo, and the Mayor gets to pretend that the city could build a lot more affordable housing if it weren’t for the NIMBYs. Within this ongoing stand-off, criticizing one side could appear like defending the other. To avoid any confusion, therefore, I would like to spend this section directly criticizing the city government and its leadership before I continue with Fox and the NIMBYs.

During the recent California Democrats conference Downtown, Mayor Robert Garcia said Long Beach was much more conservative 10 years ago than it is now, and claimed, “Today, this city is leading the way on… economic justice…”

Ah! The sort of vague boast that one would only ever attempt in the safety of a political rally, where, with the mundanity of a period, every sentence is punctuated with roaring applause. I’m sure we are all thrilled to know that Long Beach has finally been deemed progressive enough to host a CADEM conference; but then perhaps our elected officials should also have the humility to realize that they are following California’s lead—not the other way around.

To me, any city that continuously rolls over to whichever interest happens to be the most monied and organized and privileged at the time, cannot call itself a leader on much of anything, let alone economic justice. Yet the City of Long Beach did roll over, and over, and over for nearly a decade while the Downtown Plan displaced many of our residents; and then the City of Long Beach rolled over, and over, and over again for one full year while the Land Use Element was shredded piece-by-piece in the interests of property-“owners.” Is that “leading the way”?

Leadership cannot mean passing, as the City Council did in May of this year, a modest tenant relocation assistance ordinance—and doing so for some strange reason without making it retroactive to the date of its passage, or at least including a moratorium to prevent evictions until it took effect—almost one full decade after the Downtown Plan was passed, and after thousands of residents had already been displaced.

Leadership cannot mean passing, several months later in November, a very brief moratorium on no-cause evictions after the state government effectively cornered cities to do so by passing state-wide renter protections (AB 1482). Keep in mind that just a few years ago, when housing activists wanted to pass Just Cause Eviction protections (a humble request compared to rent stabilization), the conversation couldn’t even get out of the Human Relations Commission because our local class of locusts—the landlords [3]—swarmed over the narrative and consumed it until there was nothing left.

So, yes, the City Council recently passed a moratorium on no-cause evictions; but it also risked almost nothing in doing so—as evidenced by the lack of landlord testimony during the meeting, by the number of cities that accomplished this before Long Beach, and by the council’s unanimous vote. [4] It is pure cynicism to bow to developers when they’re the most powerful (the Downtown Plan), and then bow to landlords when they’re the most powerful (Just Cause Eviction), and then bow to single-family home-“owners” when they’re the most powerful (the LUE), and then bow to the state government when it’s the most powerful (AB 1482). That is not leadership! That’s crawling with your head down through the trenches of other peoples’ struggle.

You can still walk through the neighborhoods surrounding Cesar Chavez Park and Drake Park and see whole multi-family units gutted. Why didn’t they get to stay home for the holidays? Where is the reckoning for those who have stolen this city from so many working-class families? Where are the apologies? Where is the restitution? Where is the “economic justice”?

III.

Of Mice and Men

“The truth is whenever you put a population too densely together crime always goes up. And it’s not because any individual being bad, [sic] it’s because it’s the nature of mammals. You put too many rats in a cage and they’ll start eating each other.”

– Robert Fox, in a profile of the 2nd District candidate in the Long Beach Post.

Though I’m sure the reader is as aware as I am that the standards for even the highest public office aren’t exactly high, I still think a statement like this should disqualify a candidate. I am going to spend the next two sections of this essay discussing the implications of this quote, because I believe it offers us a clear and honest window into Fox’s worldview.

To begin, we could bore the reader with a long list of the differences between rats and humans, but perhaps it suffices to merely point out the other aspects of the analogy that make zero sense: cities aren’t cages; density doesn’t cause crime; human beings don’t resort to cannibalism in city environments—literally or metaphorically; the best way to make a person crazy is not to throw them in a crowded cell with other people, but to isolate them from all human contact for prolonged periods; and while rats are indeed mammals, the mammalian group includes a wide array of living things—from humans to whales to giraffes—and so to simply lump all mammals together as synonymous with rats is to ignore a large body of contradicting natural phenomena. Just to expand briefly with some examples: giraffes are herbivores and have long necks; whales are bigger than busses and have blowholes; rats tend to hang around dark places underground; and humans tend to do things like, I don’t know, create art and music and, whether Robert Fox likes it or not, live socially in these things called cities.

If you think the above paragraph is a little too obvious—or maybe a little too obnoxious; or both—then please understand that I think Fox’s analogy is a little too inane. [5]

Therefore, concerning “the nature of mammals,” we can dismiss the “mammal” part as too broad a category to mean much of anything when the subject is how many humans should live in a single space.

Additionally, there is the irony that restricting new development—as Fox advocates—helps create situations in which lower-income people are forced to live in the crowded conditions Fox claims to oppose. (Contradictions like this suffuse the politics of single-family neighborhood advocates.) Fox even proposes as part of his campaign platform that, while apparently the east side of the 2nd District should be left completely alone, the Downtown area is the perfect spot to shove people into shipping containers.

So let’s summarize: Fox believes density causes cannibalism, but also thinks only certain portions of the district he is running to represent should be protected from said cannibalism, while other areas should begin squeezing people into less and less space, and prepare them for consumption…

And yet, despite the preponderance of such crowded conditions, lower-income residents currently living in these spaces haven’t yet cannibalized each other. I’ll leave that head-scratcher to the biologists. I invite Fox to do the same.

III.

Of Mice and Men

“The truth is whenever you put a population too densely together crime always goes up. And it’s not because any individual being bad, [sic] it’s because it’s the nature of mammals. You put too many rats in a cage and they’ll start eating each other.”

– Robert Fox, in a profile of the 2nd District candidate in the Long Beach Post.

Though I’m sure the reader is as aware as I am that the standards for even the highest public office aren’t exactly high, I still think a statement like this should disqualify a candidate. I am going to spend the next two sections of this essay discussing the implications of this quote, because I believe it offers us a clear and honest window into Fox’s worldview.

To begin, we could bore the reader with a long list of the differences between rats and humans, but perhaps it suffices to merely point out the other aspects of the analogy that make zero sense: cities aren’t cages; density doesn’t cause crime; human beings don’t resort to cannibalism in city environments—literally or metaphorically; the best way to make a person crazy is not to throw them in a crowded cell with other people, but to isolate them from all human contact for prolonged periods; and while rats are indeed mammals, the mammalian group includes a wide array of living things—from humans to whales to giraffes—and so to simply lump all mammals together as synonymous with rats is to ignore a large body of contradicting natural phenomena. Just to expand briefly with some examples: giraffes are herbivores and have long necks; whales are bigger than busses and have blowholes; rats tend to hang around dark places underground; and humans tend to do things like, I don’t know, create art and music and, whether Robert Fox likes it or not, live socially in these things called cities.

If you think the above paragraph is a little too obvious—or maybe a little too obnoxious; or both—then please understand that I think Fox’s analogy is a little too inane. [5]

Therefore, concerning “the nature of mammals,” we can dismiss the “mammal” part as too broad a category to mean much of anything when the subject is how many humans should live in a single space.

Additionally, there is the irony that restricting new development—as Fox advocates—helps create situations in which lower-income people are forced to live in the crowded conditions Fox claims to oppose. (Contradictions like this suffuse the politics of single-family neighborhood advocates.) Fox even proposes as part of his campaign platform that, while apparently the east side of the 2nd District should be left completely alone, the Downtown area is the perfect spot to shove people into shipping containers.

So let’s summarize: Fox believes density causes cannibalism, but also thinks only certain portions of the district he is running to represent should be protected from said cannibalism, while other areas should begin squeezing people into less and less space, and prepare them for consumption…

And yet, despite the preponderance of such crowded conditions, lower-income residents currently living in these spaces haven’t yet cannibalized each other. I’ll leave that head-scratcher to the biologists. I invite Fox to do the same.

IV.

Hurrah! Another Year, Surely This One Will Be Better Than the Last; The Inexorable March of Progress Will Lead Us All to Happiness

Next, let’s talk about the other part of “the nature of mammals”: nature.

There is nothing “natural” about the suburbs. Humans existed fine without them for millennia, and we’ll be fine without them when they’re gone. This is true whether you perceive “nature” as something separate from humans, or something indistinguishable from us.

In the latter case, anything humans do is by definition “natural,” and therefore skyscrapers are just as “natural” as Craftsman front porches. Appeals to “nature” thus have no power to determine which path is best. Often, someone merely evokes a small, isolated example of “nature” in order to advocate for what is, after all, their own very human desire. The Fox quote above is a perfect example.

And in the former case of “nature”—where the concept is presented as antithetical to humanity—humans have been increasingly separating themselves from nature while simultaneously dominating it. Under this definition, the most “unnatural” strategy for development would logically be whichever development was the most recent one in our collective history. Thus, congregations of human beings in close proximity—i.e., truly social living: cities, tribes, towns, etc.—are much more “natural” than exclusive and separate familial subdivisions.

To continue with this former case of the word: the “natural” development of human cities is for increasingly expensive land to be occupied by increasingly larger buildings. This makes sense because if land continues to increase in cost as an economy develops, then theoretically more people would have to work together to afford any single plot of land. In doing so they sacrifice space, yes, but it is worth it for what they gain in connection, culture, and opportunity. Notice also that as humans congregate, locations respond by getting more expensive—which is an economic signal that tells us what? Humans value density.

Therefore, what is it that stops denser, tighter development from happening as land increases in cost?

Privilege and violence.

If the “natural” development as land increases in cost is for humans to congregate closer together to afford that land, then what is it that allows a small percentage of people to keep expensive land for themselves?

Privilege and violence.

Public services—roads, police, fire departments, pipes, electricity, democratic institutions, etc.—cost more money per resident when humans are sprawled out over larger and larger territories. The environment—both from a raw, land acreage perspective, but also more importantly from the resources involved in travel—takes greater damage when humans are sprawled out. What exactly is “natural” about that? How much of Los Angeles’ former “natural” glory has been paved over by single-family neighborhoods? When are we going to commit to undoing the damage this development has caused?

Imagine that with more multi-family homes—i.e., with taller buildings where economics and ecology and basic human decency tell us they should be—Los Angeles could have green belts: forests and wildlife and rivers; trees next to other trees instead of tucked into isolated patches of dirt like a taunting archipelago of the past. Such cities are not the stuff of mere fantasy—they would be the product of a truly collective approach and collective vision for human development.

IV.

Hurrah! Another Year, Surely This One Will Be Better Than the Last; The Inexorable March of Progress Will Lead Us All to Happiness

Next, let’s talk about the other part of “the nature of mammals”: nature.

There is nothing “natural” about the suburbs. Humans existed fine without them for millennia, and we’ll be fine without them when they’re gone. This is true whether you perceive “nature” as something separate from humans, or something indistinguishable from us.

In the latter case, anything humans do is by definition “natural,” and therefore skyscrapers are just as “natural” as Craftsman front porches. Appeals to “nature” thus have no power to determine which path is best. Often, someone merely evokes a small, isolated example of “nature” in order to advocate for what is, after all, their own very human desire. The Fox quote above is a perfect example.

And in the former case of “nature”—where the concept is presented as antithetical to humanity—humans have been increasingly separating themselves from nature while simultaneously dominating it. Under this definition, the most “unnatural” strategy for development would logically be whichever development was the most recent one in our collective history. Thus, congregations of human beings in close proximity—i.e., truly social living: cities, tribes, towns, etc.—are much more “natural” than exclusive and separate familial subdivisions.

To continue with this former case of the word: the “natural” development of human cities is for increasingly expensive land to be occupied by increasingly larger buildings. This makes sense because if land continues to increase in cost as an economy develops, then theoretically more people would have to work together to afford any single plot of land. In doing so they sacrifice space, yes, but it is worth it for what they gain in connection, culture, and opportunity. Notice also that as humans congregate, locations respond by getting more expensive—which is an economic signal that tells us what? Humans value density.

Therefore, what is it that stops denser, tighter development from happening as land increases in cost?

Privilege and violence.

If the “natural” development as land increases in cost is for humans to congregate closer together to afford that land, then what is it that allows a small percentage of people to keep expensive land for themselves?

Privilege and violence.

Public services—roads, police, fire departments, pipes, electricity, democratic institutions, etc.—cost more money per resident when humans are sprawled out over larger and larger territories. The environment—both from a raw, land acreage perspective, but also more importantly from the resources involved in travel—takes greater damage when humans are sprawled out. What exactly is “natural” about that? How much of Los Angeles’ former “natural” glory has been paved over by single-family neighborhoods? When are we going to commit to undoing the damage this development has caused?

Imagine that with more multi-family homes—i.e., with taller buildings where economics and ecology and basic human decency tell us they should be—Los Angeles could have green belts: forests and wildlife and rivers; trees next to other trees instead of tucked into isolated patches of dirt like a taunting archipelago of the past. Such cities are not the stuff of mere fantasy—they would be the product of a truly collective approach and collective vision for human development.

V.

The Suburbs are a Lie

Clutching to a strange developmental relic of the 1950s, however, is a great way in the long-run of making everything worse for everyone. After all, are the suburbs even sustainable for the tiny fraction of humanity currently enjoying the exclusivity of their use? Or are we all paying the price—just in different amounts and at different times—for a vision that mainly benefits the banks?

A very, very small percentage of people, in the long-run, actually benefit from the myth of single-family neighborhoods. The national mortgage banker, American Financing, estimated that 44 percent of Americans between the ages of 60 and 70 will still have a mortgage when they retire. That does not mean 56 percent have paid their mortgage off, however, because the number of retirees who are renting is also growing.

And that’s just counting Americans. Remember, when we talk percentages, we cannot always confine ourselves to the provincial. What is the home-“owner” rate, really, when we account for the entire people of the Earth? And I argue we must make our lens wider—ever wider—to counter the two block radius now burning the sockets of our unfortunate brothers and sisters who temporarily occupy bank-owned land.

So are any of us actually riding off into the sunset? Or are we all fighting over thrones of mud? Is it really “natural” for large numbers of humans to be collecting a debt they cannot pay as they grow old? All while significant percentages of us are exploited by rent, war, and borders? Wouldn’t it be more “natural” to collect friends, experiences, happiness, security, and debt-free wealth? Wouldn’t it be more “natural” for poverty to not exist?

V.

The Suburbs are a Lie

Clutching to a strange developmental relic of the 1950s, however, is a great way in the long-run of making everything worse for everyone. After all, are the suburbs even sustainable for the tiny fraction of humanity currently enjoying the exclusivity of their use? Or are we all paying the price—just in different amounts and at different times—for a vision that mainly benefits the banks?

A very, very small percentage of people, in the long-run, actually benefit from the myth of single-family neighborhoods. The national mortgage banker, American Financing, estimated that 44 percent of Americans between the ages of 60 and 70 will still have a mortgage when they retire. That does not mean 56 percent have paid their mortgage off, however, because the number of retirees who are renting is also growing.

And that’s just counting Americans. Remember, when we talk percentages, we cannot always confine ourselves to the provincial. What is the home-“owner” rate, really, when we account for the entire people of the Earth? And I argue we must make our lens wider—ever wider—to counter the two block radius now burning the sockets of our unfortunate brothers and sisters who temporarily occupy bank-owned land.

So are any of us actually riding off into the sunset? Or are we all fighting over thrones of mud? Is it really “natural” for large numbers of humans to be collecting a debt they cannot pay as they grow old? All while significant percentages of us are exploited by rent, war, and borders? Wouldn’t it be more “natural” to collect friends, experiences, happiness, security, and debt-free wealth? Wouldn’t it be more “natural” for poverty to not exist?

VI.

In Which Hegel Enjoys a Lovely Bike Ride Down Broadway

In pursuit of greater understanding of the contradictions of capitalism and its day-to-day vanguard in the United States—“middle class,” single-family home-“owners”—I have a few questions. I hope the varying degrees of sarcasm within them are seen by the reader as evidence of my (our?) frustration, and that the questions are allowed therefore the space to be genuine expressions of confusion and disbelief:

- What could be more American than the right to do what you want with your property?

- Doesn’t local zoning via mob rule blatantly contradict the private right to do with your land whatever you see fit? (Remember that hilarious bit about democracy being two wolves and one sheep voting on lunch?)

- Isn’t resorting immediately to government violence in order to prevent construction of new homes a kind of Central Committee tactic? (If you think government violence doesn’t ultimately underlay all exclusive housing policies, try to build a studio in your backyard, or a manger in a public park, or try to cross a national border, and see what happens.)

- Aren’t zoning laws actually just another form of Central Planning?

- We won the Cold War. [6] Haven’t Americans earned the right to buy and sell property without having to also earn the approval of mobs of home-“owners,” who think wide swaths of land belong to their collective interest, and not to individuals with individual rights?

- Is it not rather obscene, and indicative of a kind of Tyranny, to impose, via government mandate, wholesale bans on the construction of buildings that house multiple families? (Yet that is exactly what “zoning” is: a government ban on the ingenuity of entrepreneurs from providing goods and services through the “free market.”)

These contradictions, and others mentioned throughout this essay, expose what is generally referred to as capitalist “ideology.” What does that mean? And why should it be exposed?

Sometimes, when we think of “ideology,” we use the term synonymously with “philosophy” or “general political leaning,” and thus we may think of it as some kind of reasoned intellectual stance—a more-or-less conscious construction of policy positions, derived from principles, or deduced from empirical studies, or geared towards a specific, socially-minded teleology, or some mix thereof. That is what Merriam-Webster will also tell you.

Indeed, “ideology,” as I define it, actively participates in this illusion: it is decorated with verbal arguments, and then presented as a competent series of policy positions based on reasoning or research or values. Underneath this linguistic facade, however, “ideology” is just the knee-jerk defense of class interest, donning whatever form happens to suit its needs—i.e., it invents reasons after it has determined its own benefit. [7] (This is an unconscious process typically.)

This is why home-“owner” arguments often go in a circle if you try to grant them any kind of logic: they don’t want development because there’s not enough parking, but they won’t give up their cars because they need to drive to their jobs, but they don’t want jobs to come closer to them because they don’t want development. Any philosophy dedicated to some level of coherence would want to at least partly resolve these contradictions; but “ideology” contents itself with hopping around the circle ad hoc, defending its own interests against whatever it perceives to be the most immediate threat.

This is why the “ideology” of the home-“owner” in modern times occasionally leans on hailing free markets or defending private property. Those are both arguments that in 2019 will guarantee you an audience, even with “progressive” governments; so the home-“owners” will use those concepts to pretend their defense of single-family zoning is based on principle, when it is clearly based on their perceived self-interest.

For example, note that the “free market” is a valid appeal for the home-“owner”—or, more widely, the property-“owner”—when threatened by the subjects of rent control or taxation; but then the “free market” is nowhere near their tongue when discussing zoning, or the huge amount of valuable land that has to be owned by the government because instead of it being open to private development it has to be reserved for parking, streets, and highways. How does restricting the supply of housing via government regulation square with the belief that markets are efficient and fair and should be allowed to function?

And as for “private property”: even if we take the most shallow view of property rights—that they apply literally to whoever has the title to a piece of land, and that only titleholders, or those who pay titleholders, have a right to exist on the planet—how exactly are property rights respected when collectivist neighborhood associations can restrict the freedom of title-holders to do what they want with their property?

As far as I can tell, the arguments of home-“owners” have nothing to do with “free markets” or “private property”—those are just words they use to defend a system that currently benefits their interests; words that allow them to pretend they have an argument based on something other than privilege and violence.

That is what “ideology” means—but why should it be exposed? Well, doing so is useful not just in the hope that the home-“owner” who encounters their own politics in the mirror will recognize how selfish it is and stop, but also in the hope that the rest of us can cease pretending home-“owner” arguments should be met and fought on their own linguistic terms, since those terms are a front. We have to get beyond them, and redefine the discussion to better suit the future we wish to create.

VI.

In Which Hegel Enjoys a Lovely Bike Ride Down Broadway

In pursuit of greater understanding of the contradictions of capitalism and its day-to-day vanguard in the United States—“middle class,” single-family home-“owners”—I have a few questions. I hope the varying degrees of sarcasm within them are seen by the reader as evidence of my (our?) frustration, and that the questions are allowed therefore the space to be genuine expressions of confusion and disbelief:

- What could be more American than the right to do what you want with your property?

- Doesn’t local zoning via mob rule blatantly contradict the private right to do with your land whatever you see fit? (Remember that hilarious bit about democracy being two wolves and one sheep voting on lunch?)

- Isn’t resorting immediately to government violence in order to prevent construction of new homes a kind of Central Committee tactic? (If you think government violence doesn’t ultimately underlay all exclusive housing policies, try to build a studio in your backyard, or a manger in a public park, or try to cross a national border, and see what happens.)

- Aren’t zoning laws actually just another form of Central Planning?

- We won the Cold War. [6] Haven’t Americans earned the right to buy and sell property without having to also earn the approval of mobs of home-“owners,” who think wide swaths of land belong to their collective interest, and not to individuals with individual rights?

- Is it not rather obscene, and indicative of a kind of Tyranny, to impose, via government mandate, wholesale bans on the construction of buildings that house multiple families? (Yet that is exactly what “zoning” is: a government ban on the ingenuity of entrepreneurs from providing goods and services through the “free market.”)

These contradictions, and others mentioned throughout this essay, expose what is generally referred to as capitalist “ideology.” What does that mean? And why should it be exposed?

Sometimes, when we think of “ideology,” we use the term synonymously with “philosophy” or “general political leaning,” and thus we may think of it as some kind of reasoned intellectual stance—a more-or-less conscious construction of policy positions, derived from principles, or deduced from empirical studies, or geared towards a specific, socially-minded teleology, or some mix thereof. That is what Merriam-Webster will also tell you.

Indeed, “ideology,” as I define it, actively participates in this illusion: it is decorated with verbal arguments, and then presented as a competent series of policy positions based on reasoning or research or values. Underneath this linguistic facade, however, “ideology” is just the knee-jerk defense of class interest, donning whatever form happens to suit its needs—i.e., it invents reasons after it has determined its own benefit. [7] (This is an unconscious process typically.)

This is why home-“owner” arguments often go in a circle if you try to grant them any kind of logic: they don’t want development because there’s not enough parking, but they won’t give up their cars because they need to drive to their jobs, but they don’t want jobs to come closer to them because they don’t want development. Any philosophy dedicated to some level of coherence would want to at least partly resolve these contradictions; but “ideology” contents itself with hopping around the circle ad hoc, defending its own interests against whatever it perceives to be the most immediate threat.

Tomisin Oluwole

Ode to Pink II, 2020

Acrylic and marker on paper

14 x 22 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

This is why the “ideology” of the home-“owner” in modern times occasionally leans on hailing free markets or defending private property. Those are both arguments that in 2019 will guarantee you an audience, even with “progressive” governments; so the home-“owners” will use those concepts to pretend their defense of single-family zoning is based on principle, when it is clearly based on their perceived self-interest.

For example, note that the “free market” is a valid appeal for the home-“owner”—or, more widely, the property-“owner”—when threatened by the subjects of rent control or taxation; but then the “free market” is nowhere near their tongue when discussing zoning, or the huge amount of valuable land that has to be owned by the government because instead of it being open to private development it has to be reserved for parking, streets, and highways. How does restricting the supply of housing via government regulation square with the belief that markets are efficient and fair and should be allowed to function?

And as for “private property”: even if we take the most shallow view of property rights—that they apply literally to whoever has the title to a piece of land, and that only titleholders, or those who pay titleholders, have a right to exist on the planet—how exactly are property rights respected when collectivist neighborhood associations can restrict the freedom of title-holders to do what they want with their property?

As far as I can tell, the arguments of home-“owners” have nothing to do with “free markets” or “private property”—those are just words they use to defend a system that currently benefits their interests; words that allow them to pretend they have an argument based on something other than privilege and violence.

That is what “ideology” means—but why should it be exposed? Well, doing so is useful not just in the hope that the home-“owner” who encounters their own politics in the mirror will recognize how selfish it is and stop, but also in the hope that the rest of us can cease pretending home-“owner” arguments should be met and fought on their own linguistic terms, since those terms are a front. We have to get beyond them, and redefine the discussion to better suit the future we wish to create.

VII.

A Few Dialectical Critiques of the “Middle Class”

My hope, therefore, is that redefining the issues surrounding home-“ownership” will allow us to direct our attention towards a better future for us all. This is why I conceptualize single-family home-“owners,” as a class, to be something less of a movement based on principles and vision, and more of a reactionary collection of unwitting soldiers for the real land-owning class: the banks.

After all, someone has to do the day-to-day dirty-work for capitalism as it imagines that ownership of wealth is a question of ingenuity and hard work instead of exclusion and control. Home-“owners” are central to that lie, and, as a kind of buffer, act as the first line of defense against all progress towards socializing economic opportunities. This buffer, in fact, has struck me as one of the main reasons for inventing a “middle class,” and so I will here attempt to redefine our understanding of that concept.

Remember that “ideology,” by my definition, is a linguistic cover for raw political power, and as such it invents concepts. The importance of this is not necessarily to criticize the concepts as such, so much as to dismiss them, and attempt instead to understand who benefits from their use. Through this lens, the “middle class” can be viewed, not as an empirical category, but an ideological one, serving as a buffer for capitalism in at least two useful ways:

One, the myth of the “middle class” dangles before our collective hamster-wheel (hamsters are also mammals, by the way), its vision of life—in which you work hard for 40 years to pay a mortgage for a home you’ll never actually own—as the grand ideal of personal responsibility and success within our culture, all while telling us to ignore the man behind the curtain: the people who receive the mortgage payments. [8] Thus it keeps all our eyes off the easy, guiltless lives of the global elite, and our hands off the easy, unearned incomes of the rentier class.

And two, it demarcates the working peoples of the world into various sub-groups, thus preventing them from recognizing their shared relationship to certain exploitations and fighting as one people. A tangible example of this is how renters view themselves as renters because they pay rent, but somehow home-“owners,” by the mere virtue of having signed a mortgage, get to pretend that their relationship to their house payment is remarkably different from a tenant’s relationship to rent. In the long-run, in the grand scheme: it isn’t.

Yet this assumption in our culture—that paying rent is very different from paying a mortgage—masks the underlying relationship of rent, in an economic sense, and it thus obfuscates not only our understanding of the issue, but also our ability to advocate for the only solution. [9]

Remember: most of the home-“owners” still have mortgages. If the economy crashed tomorrow, the banks would take their homes, just as quickly as the 30-day notices handed out to Long Beach renters every month.

Sorry—the banks wouldn’t literally take their homes, of course. Why would the banks want a bunch of empty homes? The global elite already have multiple homes, and vacation homes, and whole islands and lakes and coastlines for playgrounds, etc. Much easier to let people stay in their homes for a series of easy monthly payments spanning, say, a few decades.

Oh, but don’t call it rent! It’s definitely not rent! Nothing like rent! Monthly payment for the exclusive use of a space has no resemblance to rent! We’re not renters!

Ahem.

So in the event of a crash, the banks would swoop in, just like they did during the crash of 2008.

The home-“owners” have much less wealth, and much fewer assets, and much less power, and much less security than they think they do. Yet the banks hardly need to spend a dime on propaganda with these folks out here, organized into angry neighborhood associations, either pretending they haven’t given 40 years of their life to Bank of America, or that, having done so, they’ve earned the right to rob someone else for the 40 years that follow.

VII.

A Few Dialectical Critiques of the “Middle Class”

My hope, therefore, is that redefining the issues surrounding home-“ownership” will allow us to direct our attention towards a better future for us all. This is why I conceptualize single-family home-“owners,” as a class, to be something less of a movement based on principles and vision, and more of a reactionary collection of unwitting soldiers for the real land-owning class: the banks.

After all, someone has to do the day-to-day dirty-work for capitalism as it imagines that ownership of wealth is a question of ingenuity and hard work instead of exclusion and control. Home-“owners” are central to that lie, and, as a kind of buffer, act as the first line of defense against all progress towards socializing economic opportunities. This buffer, in fact, has struck me as one of the main reasons for inventing a “middle class,” and so I will here attempt to redefine our understanding of that concept.

Remember that “ideology,” by my definition, is a linguistic cover for raw political power, and as such it invents concepts. The importance of this is not necessarily to criticize the concepts as such, so much as to dismiss them, and attempt instead to understand who benefits from their use. Through this lens, the “middle class” can be viewed, not as an empirical category, but an ideological one, serving as a buffer for capitalism in at least two useful ways:

One, the myth of the “middle class” dangles before our collective hamster-wheel (hamsters are also mammals, by the way), its vision of life—in which you work hard for 40 years to pay a mortgage for a home you’ll never actually own—as the grand ideal of personal responsibility and success within our culture, all while telling us to ignore the man behind the curtain: the people who receive the mortgage payments. [8] Thus it keeps all our eyes off the easy, guiltless lives of the global elite, and our hands off the easy, unearned incomes of the rentier class.

And two, it demarcates the working peoples of the world into various sub-groups, thus preventing them from recognizing their shared relationship to certain exploitations and fighting as one people. A tangible example of this is how renters view themselves as renters because they pay rent, but somehow home-“owners,” by the mere virtue of having signed a mortgage, get to pretend that their relationship to their house payment is remarkably different from a tenant’s relationship to rent. In the long-run, in the grand scheme: it isn’t.

Yet this assumption in our culture—that paying rent is very different from paying a mortgage—masks the underlying relationship of rent, in an economic sense, and it thus obfuscates not only our understanding of the issue, but also our ability to advocate for the only solution. [9]

Remember: most of the home-“owners” still have mortgages. If the economy crashed tomorrow, the banks would take their homes, just as quickly as the 30-day notices handed out to Long Beach renters every month.

Sorry—the banks wouldn’t literally take their homes, of course. Why would the banks want a bunch of empty homes? The global elite already have multiple homes, and vacation homes, and whole islands and lakes and coastlines for playgrounds, etc. Much easier to let people stay in their homes for a series of easy monthly payments spanning, say, a few decades.

Oh, but don’t call it rent! It’s definitely not rent! Nothing like rent! Monthly payment for the exclusive use of a space has no resemblance to rent! We’re not renters!

Ahem.

So in the event of a crash, the banks would swoop in, just like they did during the crash of 2008.

The home-“owners” have much less wealth, and much fewer assets, and much less power, and much less security than they think they do. Yet the banks hardly need to spend a dime on propaganda with these folks out here, organized into angry neighborhood associations, either pretending they haven’t given 40 years of their life to Bank of America, or that, having done so, they’ve earned the right to rob someone else for the 40 years that follow.

VIII.

A Class Without Class Consciousness

As a result of believing in the capitalist “middle class” myth, home-“owners” exist in this strange no-man’s land: they don’t view themselves as the wretched of the Earth, but they also don’t view themselves as so rich they don’t have to worry about money. So what do they do? They constantly worry about money while insisting they aren’t the wretched of the Earth.

This is why I maintain that our intense cultural fear of poverty—a fear born of our responsibility for it—runs deeper in these folks than anyone else. That is why their politics relies on the one hand with tidying up the blots that poverty produces—often by sweeping them under another neighborhood’s rug; but sometimes also with small acts of noblesse oblige—and on the other hand with insisting, while in a constant panic, that at any moment, if any little thing goes wrong, or any part of the neighborhood changes without them saying so, they might be next in line to have their lives utterly ruined.

Welcome to the politics of a very guilty conscious. And all this whining goes on about the pending apocalypse of their neighborhood while all over our city each month whole families are actually having their homes stolen from them.

VIII.

A Class Without Class Consciousness

As a result of believing in the capitalist “middle class” myth, home-“owners” exist in this strange no-man’s land: they don’t view themselves as the wretched of the Earth, but they also don’t view themselves as so rich they don’t have to worry about money. So what do they do? They constantly worry about money while insisting they aren’t the wretched of the Earth.

This is why I maintain that our intense cultural fear of poverty—a fear born of our responsibility for it—runs deeper in these folks than anyone else. That is why their politics relies on the one hand with tidying up the blots that poverty produces—often by sweeping them under another neighborhood’s rug; but sometimes also with small acts of noblesse oblige—and on the other hand with insisting, while in a constant panic, that at any moment, if any little thing goes wrong, or any part of the neighborhood changes without them saying so, they might be next in line to have their lives utterly ruined.

Welcome to the politics of a very guilty conscious. And all this whining goes on about the pending apocalypse of their neighborhood while all over our city each month whole families are actually having their homes stolen from them.

IX.

You Don’t Get a Participation Trophy for Disruption

Aside from out-voting every other demographic as a kind of last resort, their favored political tactic is disruption: halting government processes with gestations concerning communism, tyranny, overpopulation, and government abuse. Robert Fox is a great example of this tactic, which I term “tantrum politics.”

In my experience, home-“owners” are the most riled up group in America—something we don’t talk about enough. Run a quick Google search for “college kids throw tantrum”, or “lefty throws tantrum”, and it won’t be hard to find people talking about it. It’s even become a kind of trope. Yet despite home-“owners” being typically decades older, their entire politics is basically one long tantrum and we normalize it and accept it and give them what they want.

Robert Fox threw several tantrums during the process to pass the LUE, and every time the city bowed to him and gave him what he wanted. When he threatened to run for mayor, current Mayor Robert Garcia met privately with him and Fox reportedly agreed not to run in exchange for two things: first, that Garcia would continue to oppose rent control; and, second, that Garcia would hold private round-table discussions on the LUE in which Fox could hand-pick the attendees and suggest more changes to the map.

The message? If you’re a home-“owner,” tantrums work.

Yet while clearly massive amounts of the local economy—including what is and is not considered acceptable politics within it—are directed, sometimes exclusively, by their interests, they still have the audacity to whine about their right to free parking, and their right to as many lanes as can fit in a street for their cars, and their right for the freeway to be accessible but not too close because it’s noisy, and their right to have their great-great-grandchildren grow up not just in the exact same geographic location as them, but to do so without a single ounce of change having been made to the surrounding architecture.

IX.

You Don’t Get a Participation Trophy for Disruption

Aside from out-voting every other demographic as a kind of last resort, their favored political tactic is disruption: halting government processes with gestations concerning communism, tyranny, overpopulation, and government abuse. Robert Fox is a great example of this tactic, which I term “tantrum politics.”

In my experience, home-“owners” are the most riled up group in America—something we don’t talk about enough. Run a quick Google search for “college kids throw tantrum”, or “lefty throws tantrum”, and it won’t be hard to find people talking about it. It’s even become a kind of trope. Yet despite home-“owners” being typically decades older, their entire politics is basically one long tantrum and we normalize it and accept it and give them what they want.

Robert Fox threw several tantrums during the process to pass the LUE, and every time the city bowed to him and gave him what he wanted. When he threatened to run for mayor, current Mayor Robert Garcia met privately with him and Fox reportedly agreed not to run in exchange for two things: first, that Garcia would continue to oppose rent control; and, second, that Garcia would hold private round-table discussions on the LUE in which Fox could hand-pick the attendees and suggest more changes to the map.

The message? If you’re a home-“owner,” tantrums work.

Yet while clearly massive amounts of the local economy—including what is and is not considered acceptable politics within it—are directed, sometimes exclusively, by their interests, they still have the audacity to whine about their right to free parking, and their right to as many lanes as can fit in a street for their cars, and their right for the freeway to be accessible but not too close because it’s noisy, and their right to have their great-great-grandchildren grow up not just in the exact same geographic location as them, but to do so without a single ounce of change having been made to the surrounding architecture.

X.

In Which “Historic” is a Synonym for “Mid-Century” is a Synonym for “When Everything was Nice Before the Civil Rights Act”

And let’s talk about architecture for a second. It says a lot to me that it is easier to have a neighborhood deemed “historic,” and therefore worthy of protection, than it is to have the people of that neighborhood deemed “historic,” and therefore worthy of protection. Rent control to preserve an actual human population? No way! Aesthetic control to preserve passing architectural fads? Sign me up!

There should be no historic neighborhoods without historic people!

The reason for this blatant contradiction (yet another prominent one in the single-family home-“owning” class) is that historical preservation has nothing to do with the abstract idea of the past, even though that is how it is presented to us. [10] Rather, it has entirely to do with the concrete reality of political power, and who does and does not have it.

Remember: “ideology,” to me, is a linguistic cover for raw political power, and so it invents concepts, such as “history.” After all, what is “history”? Who determines what happened before we were here, and what will happen after we are gone? Who decides which bits of us live on and which bits of us are erased? In truth, there is no such thing as “history”—there is only narrative and the question of who writes it.

When the day comes where we are worried less about our fictional impression of the past and more about the real people of the present, we will know the power has changed hands.

X.

In Which “Historic” is a Synonym for “Mid-Century” is a Synonym for “When Everything was Nice Before the Civil Rights Act”

And let’s talk about architecture for a second. It says a lot to me that it is easier to have a neighborhood deemed “historic,” and therefore worthy of protection, than it is to have the people of that neighborhood deemed “historic,” and therefore worthy of protection. Rent control to preserve an actual human population? No way! Aesthetic control to preserve passing architectural fads? Sign me up!

There should be no historic neighborhoods without historic people!

The reason for this blatant contradiction (yet another prominent one in the single-family home-“owning” class) is that historical preservation has nothing to do with the abstract idea of the past, even though that is how it is presented to us. [10] Rather, it has entirely to do with the concrete reality of political power, and who does and does not have it.

Remember: “ideology,” to me, is a linguistic cover for raw political power, and so it invents concepts, such as “history.” After all, what is “history”? Who determines what happened before we were here, and what will happen after we are gone? Who decides which bits of us live on and which bits of us are erased? In truth, there is no such thing as “history”—there is only narrative and the question of who writes it.

When the day comes where we are worried less about our fictional impression of the past and more about the real people of the present, we will know the power has changed hands.

XI.

“But on the other side, it didn’t say nothin’. That side was made for you and me.”

The proliferation of historic neighborhoods also reveals yet another contradiction in the single-family neighborhood ideology. Far from merely having a right to just their own lot, home-“owners” claim a right to the aesthetic and the function of every lot around them, and a right to have special lots to park their vehicles in front of every store around them, too. They fight for their right to everyone else’s space while claiming to oppose government tyranny—yet what would their lifestyles be without the myriad regulations that place artificial restrictions on building height and enact artificial mandates for parking space? And the violence of that contradiction only deepens the more global our perspective goes: where would the privilege of the home-“owner” be without the state, without prison, without borders?

I believe home-“owners,” as a class, are more interested in defending their interests than authentically engaging in the simple solution to poverty. But this must be the case when poverty is itself a symptom of property. Hence why they are more likely to disrupt processes, including development and zoning, instead of collaborating to improve or replace those processes.

Clearly the whole world cannot live in suburbs. Nor can we simply throw everyone into Idaho or Alaska, where land is cheap. (And, after all, why exactly is land cheap there?) The home-“owners” know this, but they’d rather fight to keep the Golden State to themselves than work together on even the most modest of proposals to build multi-family homes. Remember: the changes they made to the Long Beach LUE actually claimed even more space for single-family neighborhoods, not less. They explicitly don’t want to share Long Beach. They explicitly want to keep it for themselves. And they’re using government violence to do so.

XI.

“But on the other side, it didn’t say nothin’. That side was made for you and me.”

The proliferation of historic neighborhoods also reveals yet another contradiction in the single-family neighborhood ideology. Far from merely having a right to just their own lot, home-“owners” claim a right to the aesthetic and the function of every lot around them, and a right to have special lots to park their vehicles in front of every store around them, too. They fight for their right to everyone else’s space while claiming to oppose government tyranny—yet what would their lifestyles be without the myriad regulations that place artificial restrictions on building height and enact artificial mandates for parking space? And the violence of that contradiction only deepens the more global our perspective goes: where would the privilege of the home-“owner” be without the state, without prison, without borders?

I believe home-“owners,” as a class, are more interested in defending their interests than authentically engaging in the simple solution to poverty. But this must be the case when poverty is itself a symptom of property. Hence why they are more likely to disrupt processes, including development and zoning, instead of collaborating to improve or replace those processes.

Clearly the whole world cannot live in suburbs. Nor can we simply throw everyone into Idaho or Alaska, where land is cheap. (And, after all, why exactly is land cheap there?) The home-“owners” know this, but they’d rather fight to keep the Golden State to themselves than work together on even the most modest of proposals to build multi-family homes. Remember: the changes they made to the Long Beach LUE actually claimed even more space for single-family neighborhoods, not less. They explicitly don’t want to share Long Beach. They explicitly want to keep it for themselves. And they’re using government violence to do so.

XII.

Controlling the Narrative

It is this struggle which shifts our eyes to the larger lens through which we should view something as seemingly outrageous as a couple of bike lanes down Broadway. We should not be entertaining questions as to the efficacy of their design, or the democratic integrity of their implementation. Those are certainly subjects that people like Fox would prefer us to talk about, and that’s because making them the focus of the narrative allows the single-family home-“owner” to play victim to a local government that is, somehow, both incorrigibly inept and, at the same time, omnipotently cunning. Fox’s official campaign Facebook page gives a clear example of this sort of exasperation:

“Does the City just not care we are being hurt?

What agenda is driving this insanity?

How can they justify this dangerous design?

How low have we sunk, when our own local government has no respect or concern for the people.” [sic]

Sounds like ideology to me. If we are going to talk about a corrupt local government, are bike lanes really the pinnacle of exploitation? And are we just going to ignore the fact that car-related accidents are consistently ranked among the top killers of Americans year after year, across all age groups? Maybe more bike lanes would help…

Unfortunately, the extent to which we talk about being fed up with bike lanes is the exact extent to which we are ignoring the truly gross and opulent aspects of our local politics which deserve our attention. While examples of real exploitation continue to pour in each and every month—neatly ignored by the most dominant local class and the local government alike—these two factions simultaneously pretend to have a real, meaningful disagreement over bike lanes…

That is the state of our situation in this city! We must pierce through these false divisions and false narratives as quickly and powerfully as possible, and strike at the exploitation of the classes currently not privileged enough to warrant the attention of a road diet!

XII.

Controlling the Narrative

It is this struggle which shifts our eyes to the larger lens through which we should view something as seemingly outrageous as a couple of bike lanes down Broadway. We should not be entertaining questions as to the efficacy of their design, or the democratic integrity of their implementation. Those are certainly subjects that people like Fox would prefer us to talk about, and that’s because making them the focus of the narrative allows the single-family home-“owner” to play victim to a local government that is, somehow, both incorrigibly inept and, at the same time, omnipotently cunning. Fox’s official campaign Facebook page gives a clear example of this sort of exasperation:

“Does the City just not care we are being hurt?

What agenda is driving this insanity?

How can they justify this dangerous design?

How low have we sunk, when our own local government has no respect or concern for the people.” [sic]

Sounds like ideology to me. If we are going to talk about a corrupt local government, are bike lanes really the pinnacle of exploitation? And are we just going to ignore the fact that car-related accidents are consistently ranked among the top killers of Americans year after year, across all age groups? Maybe more bike lanes would help…

Unfortunately, the extent to which we talk about being fed up with bike lanes is the exact extent to which we are ignoring the truly gross and opulent aspects of our local politics which deserve our attention. While examples of real exploitation continue to pour in each and every month—neatly ignored by the most dominant local class and the local government alike—these two factions simultaneously pretend to have a real, meaningful disagreement over bike lanes…

That is the state of our situation in this city! We must pierce through these false divisions and false narratives as quickly and powerfully as possible, and strike at the exploitation of the classes currently not privileged enough to warrant the attention of a road diet!

XIII.

Who Owns the Earth?

I’d like to end with one final topic: rent.

The politics of the home-“owner” class is so short-sighted that, while it can often be selfish in intent, it cannot be considered wholly such in effect, because it misconceives how the self relates to the world.