The Blue Line is Receiving an Overhaul—But Will a New Reality Make for New Perceptions?

by James Andrew Carroll | Published August 18, 2018 in Perspectives

6 minute readThe council Tuesday night received a two-part report on various improvements—some already made, others still on the way—to the Metro Blue Line, which runs between the downtowns of Long Beach and Los Angeles.

The first part of the report detailed how police response times and crime rates have decreased since Metro authorities began teaming with the Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) last year. Officers have been riding the Blue Line to maintain a presence, and as a result emergency response times are below 3.5 minutes for calls in the city, and serious crimes are down 30 percent over the last 12 months. Next year, the LBPD is also adding to its Metro unit two new Quality of Life Officers, who deal exclusively with helping those experiencing homelessness access services.

The second part focused on the $350 million “New Blue” project designed to make structural and aesthetic improvements to the Metro, including upgrades that will decrease the travel-time from Long Beach to Los Angeles by an estimated 10 minutes. This last batch of financing comes at the tail-end of a 10-year overhaul that has seen about $1 billion placed into the Blue Line. Measure M, which Los Angeles County voters passed by a wide margin in November of 2016, will itself create two dozen new transit lines across the county.

But the above investments cannot fully address the large and lingering problems at the root of Metro’s declining ridership.

The first issue is gentrification. Though some affordable housing developments—such as the Spark and the Beacon—have been planned in Long Beach along the Metro route, they are few compared to the mass of market-rate and luxury development happening downtown; and when communities that have relied on public transportation are displaced by wealthier residents, ridership suffers. This has already been happening across Los Angeles.

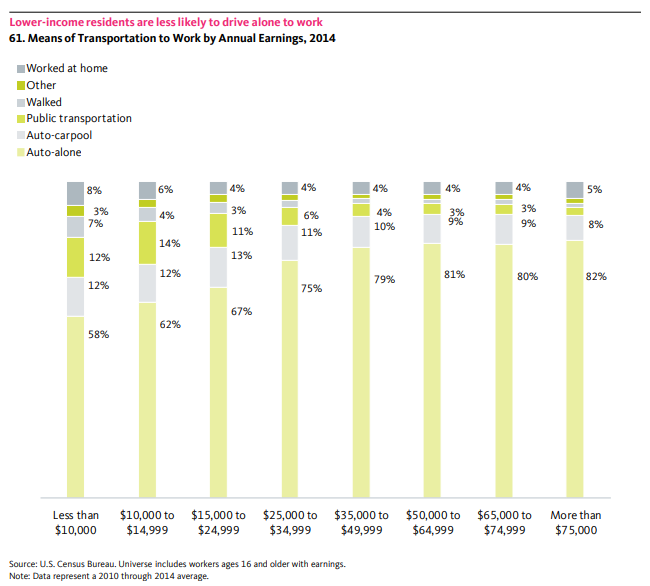

A 2017 report from Policy Link and the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE) at the University of Southern California found that 73 percent of residents in L.A. County drive to work alone. This percentage increases dramatically with income: “Only 58 percent of very low-income workers (earning under $15,000 per year) drive alone to work,” the report states (pg. 71), “compared with 82 percent of workers who make over $75,000 a year.”

As of 2016, the Blue Line had 20 of its 22 stops traversing through communities with median incomes well below the L.A. County average. Accounting for Downtown Long Beach’s ongoing developments, median incomes near the southernmost stations of the Blue Line are sure to rise, begging two questions: will these new folks ride the improved Metro? Or will they only continue displacing the people who need the Metro most?

Tomisin Oluwole

Face the Music, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 36 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Then there are concerns over how effective altering the reality of transit will be at affecting the perceptions and lifestyles of Southern Californians. The Blue Line has struggled for years with its public image, and mass transit across L.A. is seen as less effective and accessible than it actually is. From 2013 to 2017, Metro ridership declined almost 20 percent. The growth of ride-sharing companies, falling gas prices from 2012 to 2015, and gentrification may have all played a part.

Further working against any optimism is the foundation of Los Angeles transportation: historically unique, largely suburban, and car-centered, it creates issues, not just for the existing transit infrastructure, but with an existing culture that prevents many residents from stepping foot on a bus to begin with. Will improvements in transit safety, or even a full aesthetic reboot, get people out of their cars and onto the bus?

During public testimony at this past week’s city council meeting, Mayor Robert Garcia, who was elected to the Metro Board last year, stated that, after an eight-month period of intermittent closures to finish the changes, there will be “a major push… to hit refresh.”

“The collective push to have that fresh start” should help increase ridership, Garcia urged. “We want people on the Blue Line.”

Progress on that front may be limited, however, by the same home-owning interests in our city who utterly had their way with the mayor and city staff all of last year and into January, effectively shrinking the city by claiming more space for suburbs—and the lonely cars that come with them—at the direct expense of shifting Long Beach into a truly urban, green, and sustainable future.

As record wildfires rage across our state, the Metro should be viewed less as a public alternative and more as an ecological necessity—but are Long Beach residents prepared to turn in their car keys for a TAP card?

If you enjoy reading independent perspectives on issues affecting Long Beach, please consider supporting local grassroots media by subscribing to FORTHE.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org