Mayor Garcia Paid the Long Beach Post $12k for Ads in March, Their Recent Article Helps Hide His Police Union Money

by James Andrew Carroll | Published July 11, 2020 in Perspectives

30 minute readThe views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of FORTHE Media.

The Long Beach Post recently published an article about the campaign finance activities of the Long Beach Police Officers Association (LBPOA) in which they gave Mayor Robert Garcia space to spread the falsehood that the committees which have received over half a million dollars from the LBPOA are not his.

Upon further investigation, however, it is clear that, not only are the committees controlled by Garcia, but one of those committees also bought $12,000 worth of ads in March from the Long Beach Post.

With this revelation in mind, the outlet’s article contains glaring omissions and biases that are worth examining. The mayor’s statement about his committees must likewise be broken down carefully and exposed.

Each must be understood within the context of the nation’s ongoing, historic protests against racism and police brutality, which have demanded police and other institutions be held accountable. The first omission in the article, in fact, is that it made uncritical space for the narratives of Garcia and city elites—including the LBPOA President—but did not reach out to the local Black Lives Matter chapter to hear their perspectives.

How can you—in this moment—write an entire article about elected officials and police unions without even mentioning Black Lives Matter or police violence against Black people?

Striking power imbalances of this kind can be spotted throughout the article, and we’ll go through many of them below, while also uncovering the truth about Garcia’s committees, and the half a million dollars of police union money he suddenly doesn’t want on his record.

FROM THE BEGINNING

In the Post article, Garcia is given a free pass to make the following claim:

“Those contributions are not contributions to me … Those ballot measures were put on by a unanimous vote by the city council and they’re city-sponsored measures on which my name has to legally appear. They’re not my committees.”

There was apparently no follow-up question from the reporter. But it would have been helpful, I think, to ask Garcia something like, “What does this have to do with City Council?”, or, “Why is your name legally required to appear?”, or, “Who authorizes the committees’ expenditures?”

Garcia’s office did not reply to a request for comment for this story. So let’s just answer those questions ourselves.

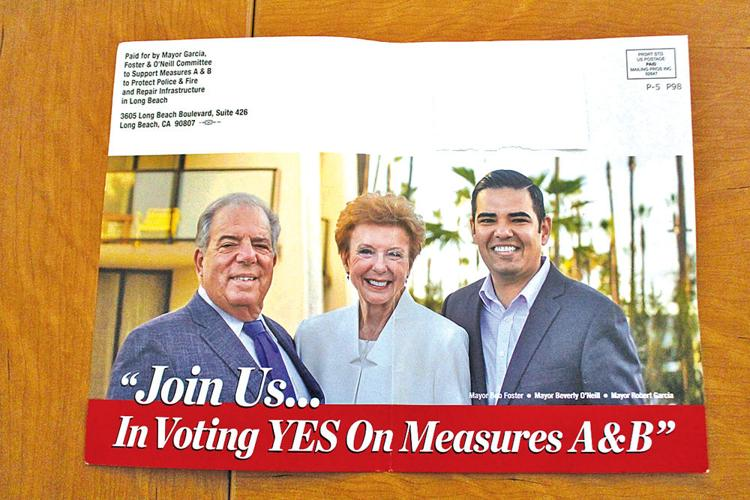

To start, it’d be useful for us to clarify that the committees in question are really just one committee, which has undergone a series of name changes through the years. When the committee first formed in March 2016, it was titled, “Mayor Garcia, Foster & O’Neill Committee to Support Measures A & B to Protect Police & Fire and Repair Infrastructure in Long Beach.”

The committee was initially set up to support two local ballot measures, one of which was Measure A—a temporary sales tax increase. The new revenue would flow into the city’s general fund but, according to the mayor, would still be earmarked for public infrastructure and public safety investments, including policing.

The Long Beach police union supported the committee almost immediately, according to campaign finance forms. Less than a month after it was set up, they had already given the committee over $100,000. Voters then passed the measures a few months later.

Fast forward four years, and the committee’s name had changed to, “Yes on A & B, Mayor Garcia Committee to Protect Police & Fire and Repair Infrastructure in Long Beach.” Its purpose this time was in part to support the new Measure A—a permanent extension of the original Measure A. Once again, the police union heavily backed the committee. This past March, Measure A was once again passed by voters.

In between all that, the committee supported several other measures—each time changing its name, and each year enjoying continued financial support from the LBPOA.

With the police union’s grip on City Hall recently attracting extra public attention, Garcia has attempted in his Post interview to erase himself from that history. His tactic relies on confusing the reader. By characterizing his ownership of these committees as some type of legal formality beyond his control, he’s left the massive amount of LBPOA donations given to these committees in limbo. With no one in control of the committees, there’s no one to be held to account for accepting and spending the money.

But this is disingenuous—and to see why, we’ll have to look at the receipts.

“THEY’RE NOT MY COMMITTEES”

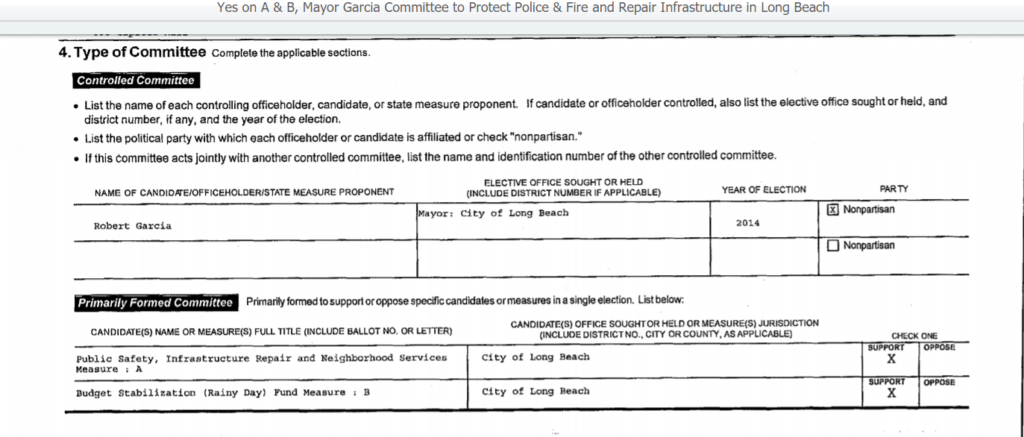

According to the Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC), if a committee is controlled by a candidate or officeholder, the committee must list that candidate’s or officeholder’s name in their “Statement of Organization” (Form 410). We can find this form, and many other ones, with some searching through the city’s campaign finance portal.

As seen below, the Form 410 for the Garcia measure committee lists his name under the “Controlled Committee” section of the document:

In fact, every Form 410 for the Garcia measure committee—even when it changes names—and every Form 410 for Garcia campaign committees, lists Garcia’s name as the officeholder who controls them. And the reason his name is listed as the controlling officeholder for campaign committees is the same reason it is listed for the measure committee: because they are all Garcia’s committees.

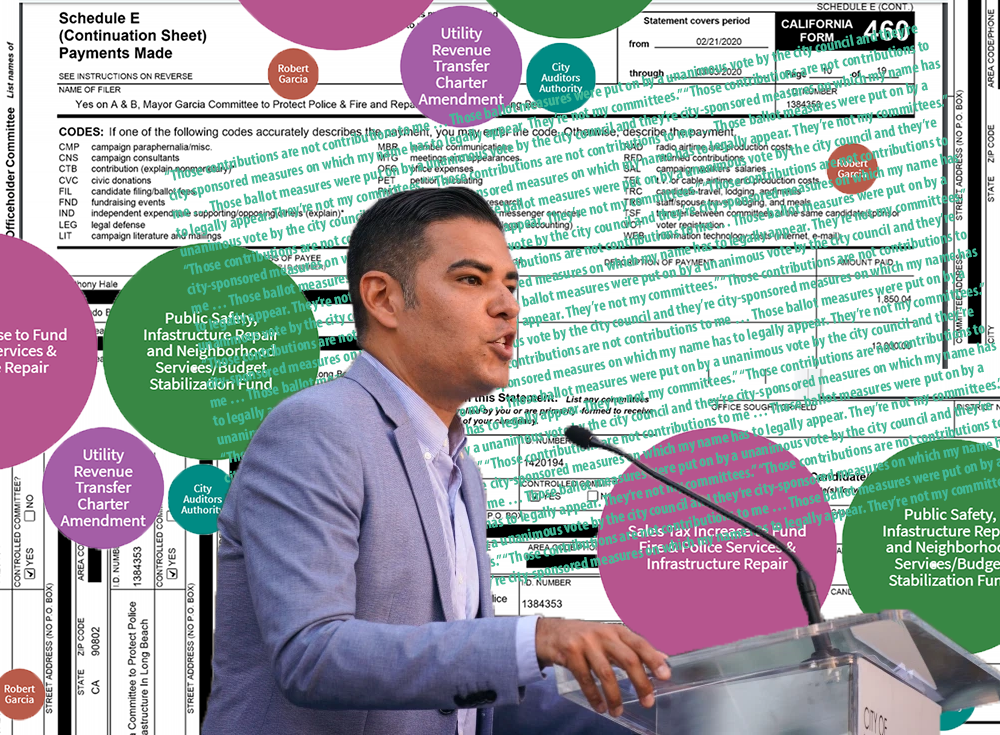

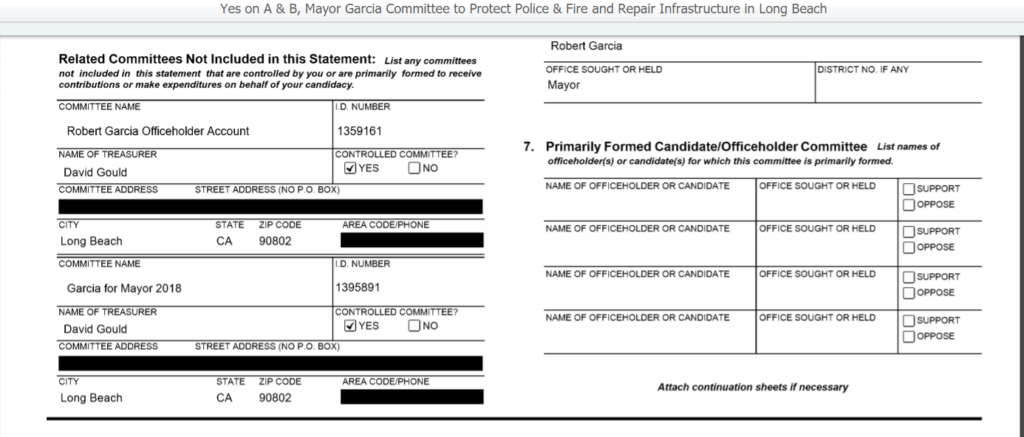

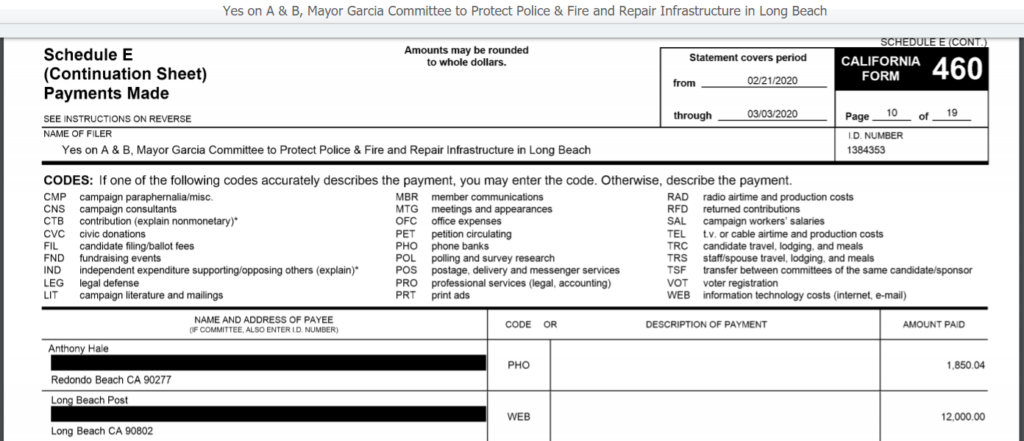

But we can take a look at even more forms to confirm this. Committees are required to periodically file a Form 460 for several things, including disclosing expenditures. The image below is a screenshot of one of the pages of a Form 460 filed by the Garcia measure committee this March:

The left hand side of the form has a section entitled, “Related Committees Not Included in this Statement,” and asks the filer to, “List any committees not included in this statement that are controlled by you…”

In that section, we see listed Garcia’s officeholder account and the Garcia for Mayor 2018 committee. Again, this is because those are just as much Garcia’s committees as the measure committee is. He legally controls all of them.

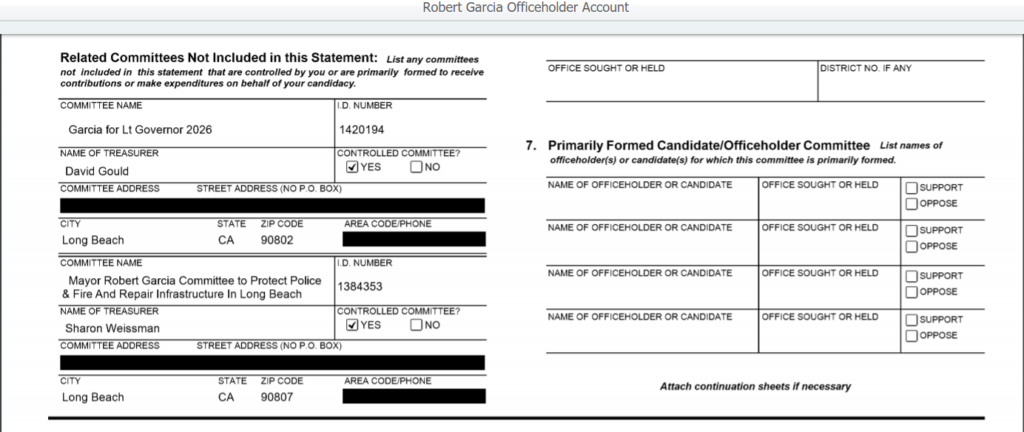

Likewise, if we take a look at a Form 460 from Garcia’s officeholder account, we can see the same thing in reverse:

This time, Garcia’s measure committee is listed in the “Related Committees” section. Again, this is because it is another committee he controls.

But that’s not all that is required. Note that the box under “Controlled Committee?” is marked “YES.” FPPC Regulation 18402(c)(1) states, “The name of a committee controlled by one or more candidates must include the last name of each candidate that controls the committee.”

And so already we know why his name is legally required to appear. As an example, one of the names of the Garcia measure committee is, “Yes on A & B, Mayor Garcia Committee to Protect Police & Fire and Repair Infrastructure in Long Beach.” This committee’s name must include Garcia’s name precisely because he controls it.

But what does “control” mean? Well, as the FPPC explains, “When a candidate for elective office, including an officeholder, exerts significant influence on the actions or decisions of a committee, it is considered a ‘controlled committee.’” (pg. 12)

Clearly therefore, the explicit legal requirement that Garcia’s name appear within the name of the committee is designed to be a notice to the public that Garcia “exerts significant influence on the actions or decisions of [the] committee.”

Read: the committee is Garcia’s committee.

“…MY NAME HAS TO LEGALLY APPEAR”

Garcia tries to dance around all this in his statement by declaring his name “has to legally appear,” and then insisting that somehow this requirement has nothing to do with his power over the committee’s decisions. It’s as if he expects us to believe that some other unnamed person is actually in charge of the committee’s spending, and for some unknown reason the FPPC doesn’t bother making the committee report who exactly that is. Instead, they force Garcia to put his name on the committee just for the heck of it.

Luckily—in case the documents already outlined above aren’t proof enough—the FPPC clarifies all of this for us. The instructions for filling out a Form 410 explain:

“A committee that is not controlled by a candidate or officeholder must disclose the name, street address, and telephone number of the committee’s principal officer(s).”

In other words, unless someone else is explicitly listed as the principal officer in the committee’s Form 410, the committee is solely run by the candidate or officeholder in control of it. In our case, this would clearly mean Garcia.

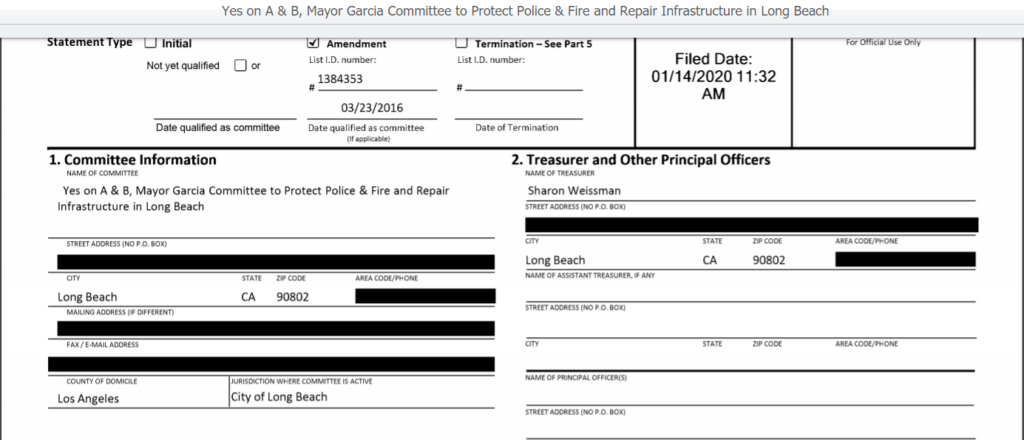

In the image below—which is of the Garcia measure committee’s most recent Form 410—you can see that the bottom-right section includes a space titled, “NAME OF PRINCIPAL OFFICER,” and that no one is listed there:

This, again, is because the committee belongs to Garcia.

Crucially, chapter 2.9 of the FPPC’s campaign finance manual defines a principal officer as, “an individual that is responsible for approving the committee’s political activity, such as… authorizing expenditures…”

In the absence of a designated principal officer, the controlling candidate or officeholder assumes those roles. That is precisely what it means for a committee to be “controlled.” This is why a committee that is “not controlled” must then “disclose … the principal officer” of the committee.

And so now we know who authorizes the committee’s expenditures: Garcia.

Lastly, Chapter 2.7 states, “…the individuals listed on the most recently filed Form 410 are liable for the committee’s activity.”

Read: Garcia is liable for the committee’s activity.

Taken together, the above documentation overwhelmingly shows that it is obscene, if not an outright lie, for the mayor to say, “They’re not my committees.”

OBSCURING THE TRUTH

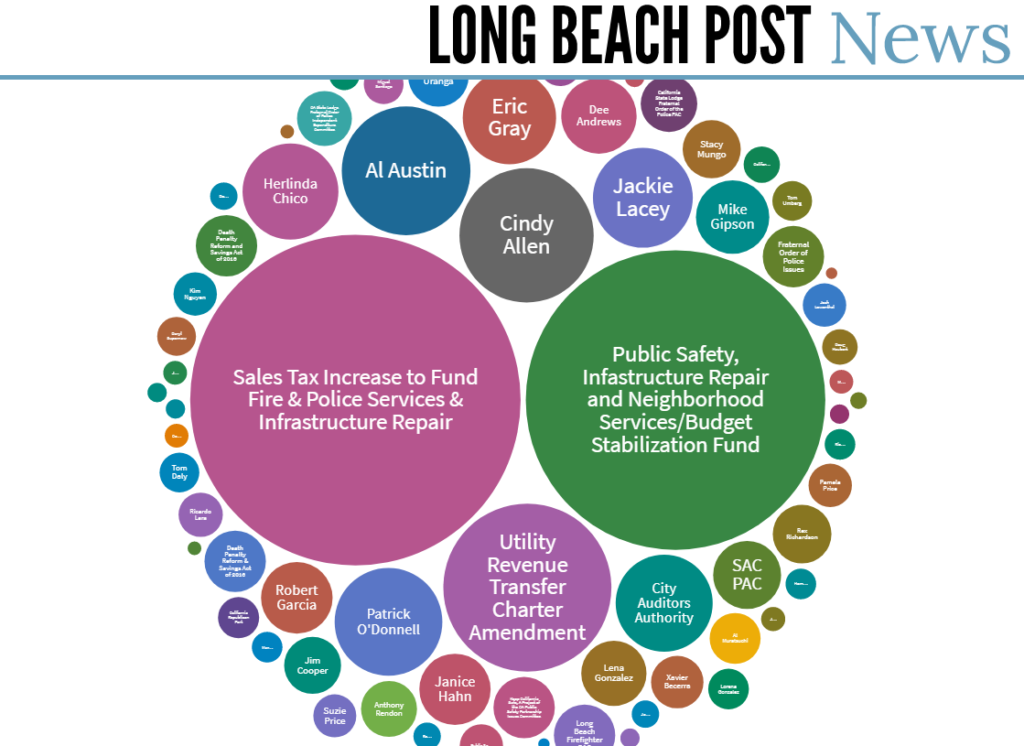

The very public purpose of committee-naming is to make the information regarding which candidate or officeholder is controlling a committee very accessible to voters. And this important public disclosure makes it all the more alarming that the Post would publish in their article an incredibly misleading graphic about those committees.

Seen below, the image removes Garcia’s name from the names of the measure committees he controls:

All three of the biggest circles in the center are Garcia-controlled measure committees, as is the circle labeled “City Auditors Authority.” These are the committees we have been discussing above. Campaign law says these committees must legally contain Garcia’s name so that the public knows who controls them; yet the Post removed his name and then re-named the committees themselves.

It’s only once you hover over each circle individually, that something resembling their legal name appears.

A more honest graphic would have either included Garcia’s name in front of all four of those titles from the start, or simply combined all four of the circles into one conglomerate circle and titled it, “Mayor Garcia’s Measure Committees.” But then that circle would have swallowed up the screen, and given the reader an idea of the truth: Garcia is far-and-away the biggest police-backed politician in the city.

No media outlet should ever give off even the slightest impression of helping an elected official obscure their political donations.

WHO CARES ABOUT $500k?

Tomisin Oluwole

Face the Music, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 36 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

Such friendly media coverage could help explain why the mayor appears to prefer speaking with the Post instead of the public. After all, Garcia had several weeks to respond to the criticisms of his relationship with the LBPOA, but chose instead to acknowledge nothing, and say nothing, about the police union money until he could have a comfortable sit-down with the Post. Why is that?

On June 6, I first reported that Garcia’s campaign and measure committees had accepted over $500,000 from the LBPOA. The Post article—which appeared almost a month later on July 3—referenced this half a million amount multiple times, but did not link to or even mention my reporting, which initially made an issue of the number.

Given how my reporting was much more critical of the number—and much more explicit about its connection to Garcia—this, again, leaves questions about the potential explicit or implicit biases of the Post’s political coverage.

My article opens with, “The Long Beach Police Officers Association (LBPOA) has donated over half a million dollars to various political committees led by Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia since 2015…”

But the Post article phrases it, “Over the past five years, the union has contributed over half a million dollars to committees supporting Measure A.”

Activists have been using the number we originally reported to point out the connection between the mayor and the police union—a connection that the Post article completely whitewashes.

Instead, the article’s author simply shrugs the number off as some kind of anomaly that people pulled out of thin air, writing, “The activists cite a figure of over $500,000, however most of that money went to ballot measures…”

The author claims this while also failing to interview the activists who have been citing the number. But maybe those activists would have explained why they feel it’s important? Instead, the author just assures us that it can’t be important, because the mayor said so.

“[THEY] ARE NOT CONTRIBUTIONS TO ME”

The reason Garcia would like us to believe these are not his committees is so that he can pretend any contributions to the committees are also not his. His false claim in the Post article opened with, “Those contributions are not contributions to me.”

That immediately makes me wonder: how did those committees raise so much money? Who exactly was doing all the fundraising?

Well, as LBReport.com revealed, it was Garcia—who not only fundraised using his own personal branding, and fundraised for multiple committees at once, but also used funds from his other committees to help pay off the accumulated debt of his measure committee.

It takes local muckrakers like LBReport’s Bill Pearl to follow Garcia’s money, especially when corporate outlets like the Post are helping to hide it. A 2009 FPPC report—“The Billion Dollar Money Train”—summarized the problems with this powerful industry of measure committees thus:

“By simply forming a ballot measure committee … candidates and officeholders have been able to circumvent contribution limits and solicit and accept contributions in unlimited amounts … These huge contributions vastly exceed what officeholders could legally accept into their own election committees.” (pg. 17)

That sounds exactly like what is happening here. The largest contribution we could find to a Garcia mayoral committee was $7,300. The largest we could find to a Garcia measure committee was $200,000. (Coincidentally, as we outlined in our first report on these numbers, that was from the LBPOA.)

In fact, in the years prior to this report, the FPPC hadn’t yet required candidates who control measure committees to place their name in the committee’s name. They implemented that rule in 2009 precisely so that the public would have clear knowledge about who controls the committee. (pg. 27)

Yet the Post article completely ignores this history, and parrots the mayor’s talking points in both text and graphics. The author of the article claims, “The POA has given the mayor a relatively modest sum…”, and the previously discussed graphic places his name in a tiny bubble in the lower left corner. Both of these tactics conveniently pretend the hundreds of thousands of dollars the POA has given to Garcia measure committees have nothing to do with him.

Ballotpedia explains why lack of clarity on these issues is so dangerous:

“Some political observers believe that politicians solicit large donations to the ballot measure committees they control, and then use those ballot measure committees for a variety of purposes, some of which involve promoting the public image and brand-name recognition of the candidate.”

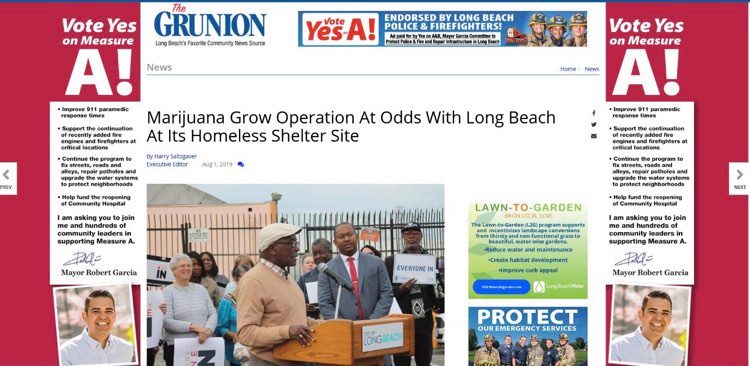

And that sounds exactly like what the mayor did with Measure A. The literature of the campaigns frequently featured his face and his endorsement. As just one example, the Grunion Gazette shared an image, below, of the very first mailer put out by the Garcia measure committee:

The mayor should not be allowed to use measure committees as slush funds for his causes and his brand, while also denying that he has any connection to the contributions they receive.

“CITY-SPONSORED MEASURES”

One paragraph within the Post article appears particularly evasive on that point, and is worth examining:

“The mayor has perhaps taken the most public criticism from protesters at local rallies for donations to his causes. The POA has given the mayor a relatively modest sum of $13,600 to directly support his election bids, but it has donated generously to ballot measures the mayor and city council support.”

That last addition of “and city council” makes the mayor seem as equally connected to the committees as every single councilmember. But as you can recall from the forms we explored above, nowhere on them did the names of any city councilmembers appear. Instead, Garcia’s name appeared. And on the ads supporting these measures, the names and faces of the entire City Council did not appear. But certainly Garcia’s name and face appeared.

The article’s narrative conflates the Garcia-controlled committees with all of City Council. That is the exact tactic utilized by Garcia in the one part of his statement we haven’t yet discussed:

“Those ballot measures were put on by a unanimous vote by the city council and they’re city-sponsored measures on which my name has to legally appear.”

Despite what the mayor would like you to believe, this sentence has absolutely nothing to do with anything; and it’s disappointing that the Post would, yet again, simply believe whatever the mayor tells them, and then lend unquestioning support to his narrative by abusing the image of “objective” journalism.

First off, the text submitted to voters for the recent Measure A, for example, did not include Garcia’s name. Nor did the city’s impartial analysis. That’s because, as we outlined at the start, it’s not the measures on which Garcia’s name has to legally appear, it’s the committees.

Second, the council voted to place a marijuana tax measure on the ballot in 2014—yet there didn’t then magically appear a mayoral committee with police union money in its pocket to support the measure.

Third, according to section 1.22.100 of the city’s municipal code, the council can place items on the ballot for voters to consider through the same process “as is prescribed in Section 8 of Article XI of the State Constitution.” That section just says that if a city requests its county to run an election for it, the county must oblige. Nowhere in these texts does it say anything about the mayor then having to form a committee, accept contributions from the police union, and spend the money on ads featuring his face.

Chapter 3 of the state Elections Code likewise deals with ballot measures, and Section 9222 specifically grants the power for a city’s own legislative body to submit an item to voters. That is the code by which the council originally submitted Measure A to voters in 2016. (pg. 3) Again, nowhere in that code, or in Chapter 3, is there anything that then mandates the mayor to start a committee, raise money, and spend it promoting his own image.

Furthermore, the city also has a Campaign Reform Act. The FPPC keeps it on file on its own website, clarifying:

“A local jurisdiction may enact a campaign ordinance that provides for additional or different campaign requirements for committees active exclusively in its jurisdiction as long as the provisions are stricter than those in the Act.”

Nowhere in Long Beach’s Campaign Reform Act is there anything that says that when a measure is placed on the ballot by City Council, the mayor must form a committee, control the committee, accept contributions to the committee, and then spend those contributions on expensive mailers.

I cannot stress enough that the mayor must be trying to confuse residents by even bringing up the notion of “city-sponsored measures” in connection to his own committees. That phrase does not appear even once in the city’s charter or municipal code. And the phrase “city measure” only appears in Chapter 1.24 of the municipal code, pertaining to the information within voter pamphlets.

Garcia appears to be using the council as nine nearby lifeboats to carry his own sinking weight. But he’s the one who has accepted over half a million dollars from the police union—not them. As discussed amply above, the committees are controlled by Garcia to largely benefit Garcia and his political projects—but now that they are being scrutinized, he wants to argue they belong to all of City Council.

The Post appears happy to take that line, but I wonder if they checked at all with Long Beach’s councilmembers to see if they see it the same way.

Finally, just because the council voted to send various measures to the ballot for voters to decide on, doesn’t mean all the councilmembers then also chose to endorse each of those measures—let alone fundraise and campaign for them. In fact, when the City Council voted to place the original Measure A on the ballot back in 2016, Garcia said:

“I think it’s important to be very clear. What the council has voted on tonight … is to give voters the opportunity to make their voices heard at the ballot box. It’s not an endorsement…” (timestamp, 51:58)

So when Garcia needed to assure residents that they would have a voice in the process, the council’s vote to place measures on the ballot was “not an endorsement.” But now that he needs to distance himself from the committees he set up to support those measures, he wants to assure you the measures are “city-sponsored.”

AD-FREE’S THE WAY TO BE

As a final revelation for the reader, the Garcia-named measure committee also sent thousands of dollars to the Long Beach Post.

Just this past March, $12,000 was paid to the outlet, as the Garcia-controlled committee made its final plea for voters to pass Measure A:

The expenditure’s “WEB” designation in the second column is defined as, “information technology costs (internet, email).” We reached out to the Post’s Publisher, David Sommers, who informed us the money went to banner ads.

We asked Sommers about the Post’s conflict of interest policy regarding such financial transactions, especially when the publication later reports on a political entity which had given them money. Sommers responded in an email, “The advertising department is wholly separate from the editorial department and has no involvement in story planning or deciding issues that warrant news coverage.”

Still, along with the Post accepting ad money from the Garcia measure committee, that committee has also accepted money from an individual with a stake in the Post’s ownership—John Molina.

Molina is one of the founding partners of Pacific6—the real estate investment firm which owns the Long Beach Post (and the Long Beach Business Journal) through its subsidiary, Pacific Community Media. According to campaign finance forms, all six founding members of Pacific6 have donated to Garcia’s mayoral committee; and Molina has also given the Garcia measure committee $25,000.

On the question of why Garcia—who co-founded the Post—does not at the very least have his name in the “Editor’s note” at the bottom of the article to disclose a potential conflict of interest for the reader, Sommers says, “It’s been nearly a decade and two owners ago since Mayor Garcia had involvement in the Long Beach Post.”

But it would be pertinent, in my opinion, for the reader to know that the committee the Post and Garcia both say isn’t Garcia’s committee, is the same committee with several financial ties between itself, Garcia, and the Post. This is especially problematic when we recall that the article also has many other omissions concerning that committee—including the facts that the committee belongs to Garcia, has accepted money from Molina, and has purchased ads from the Post.

In the forest of all this, we can almost lose sight of the fact that a political committee—which the Post has now reported on to say does not belong to Garcia—purchased banner ads from the Post. When the Grunion Gazette accepted money from the same committee last year, they ran ads that looked like this:

It’s a rather Garcia-heavy display, considering it comes from a committee that Garcia and the Post both wanna tell you isn’t his, funded by over $500k in police union dollars that Garcia and the Post both wanna tell you he never took.

The words in this essay belong solely to the author—but I hope you won’t let it stay that way. Reach out to me with ideas for art, stories, perspectives, solutions, and new politics: andrew@forthe.org. Alternatively, DM me on Instagram if that is more convenient: @oldschoolcarroll.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org