Panic Buttons: Controversial 2 a.m. vote causes four councilmembers to leave chambers in protest

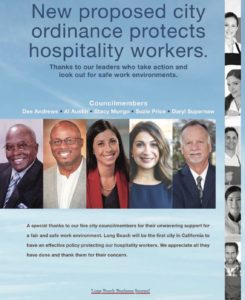

19 minute readFrom the Editors: A petitioned ordinance that would create a raft of protections for Long Beach hospitality workers will be on the Nov. 6 ballot. If passed, Measure WW would require hotels with 50 or more rooms to provide panic buttons to its employees and put restrictions on how much floor space a housekeeper can cover in a shift, among other protections against employer retaliation and guest harassment. Also known as Claudia’s Law, enacting these types of protections has been a contentious issue for city leaders for years. An attempt to craft such a policy by the more progressive faction of the council was voted down last year by Councilmembers Suzie Price, Daryl Supernaw, Stacy Mungo, Dee Andrews, and Al Austin.

Fast forward to Sept. 4: Those same five councilmembers unilaterally voted to draft a watered-down hospitality worker protection ordinance that excludes labor and retaliation measures despite a stronger, voter-petitioned version—Measure WW—already set to be on the ballot in two months. This caused Councilmembers Jeannine Pearce, Lena Gonzalez, Rex Richardson, and Roberto Uranga to walk out of the council chambers in protest.

The following is a personal perspective of that night’s events from one of our members. An audio version of this piece read by the author can also be found below the break.

Panic buttons

Last Tuesday, Sept. 4, the Long Beach City Council spent roughly seven hours dissecting and finalizing the city’s yearly budget. As the budget process came to a close, and Tuesday became Wednesday, item 26 of the evening’s council agenda took the floor. What happened next was gross—that’s the best word I have found for it so far—and everyone in the room knew it.

Just past midnight, item 26 was introduced. Over an hour and a half later, as drinkers in the surrounding downtown bars were likely being herded towards red exit signs, item 26 was passed, 5 – 0. Within that time frame, we lost roughly two hours of sleep, four members of council, and a your-mileage-may-vary measure of respect. What we gained was the dialectical clarity and shock of a cold shower.

Oh, and panic buttons—because that’s what this is all about, right? Panic buttons.

One of the more enduring myths of film history maintains that when the silent, black-and-white short, L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, first screened, it caused audience members to stampede from their seats towards the doors, fearful of being run over by the moving motion-picture locomotive, so stirring was the illusion. The members of the Long Beach public who made it past last call, and whoever else was hooked from home, can now sympathize.

Basic arithmetic dictates that five is greater than four; and basic politicking dictates that if you are part of the five, then you can tell the four to kick rocks. One-by-one, four councilmembers saw the oncoming train and removed themselves from the dais, leaving their five colleagues to do what was inevitably going to be done: panic buttons.

Because that’s what this is all about, right? Panic buttons.

My dad used to tell me, “Nothing good happens past midnight.” What follows is a partial retelling of two hours of awful behavior—a real-life conspiracy unveiled before us—from my perspective as a witness to it, and with the additional benefit of Long Beach TV’s video recording. All time-stamps refer to their online archive. The reader is encouraged to supplement this essay with a thorough watching of the actual footage.

After midnight

We are seven hours, eleven minutes, and ten seconds into the weekly Tuesday council meeting. (7:11:10) It is officially Wednesday. Mayor Robert Garcia asks the city clerk to introduce the next item, which reads:

“Communication from Councilwoman Price, Councilwoman Mungo, Vice-Mayor Andrews, Councilman Austin. Recommendation to request a series of public safety measures designed to proactively address this public safety concern…”

The motion put forward by the four listed councilmembers (hereafter: the conspirators) requests that the city attorney draft an ordinance requiring, among other things, that “all hotel and lodging employers, to include motels, shall provide an emergency contact device, often referred to as a panic button…”

Councilmembers Suzie Price (CD-3) and Stacy Mungo (CD-5), two makers of the motion, open by stating it should be uncontroversial. This is immediately contradicted when the floor opens for public testimony and two members of the public who have stayed past midnight speak against the motion; and then it is contradicted further by Councilmember Jeannine Pearce (CD-2). (7:20:01)

Pearce opens her statement by saying the item “appears to be politics, playing with hotel-workers’ lives… That’s how it feels when it’s done in this way.” Pearce says she has a lot of questions, and asks whether she should ask all her questions now, or go one at a time. Garcia answers that she can just ask all her questions at once.

Tactically, the mayor’s suggestion makes zero sense for Pearce to accept, because it forces her to lay all her cards on the table from the start, instead of getting information from one question at a time, and using the new information to ask increasingly more pointed questions while maintaining control of the floor. It left me a bit confused as to why the mayor would suggest that at all, given that it is not typically how questions are handled on the dais.

I have elected to place all of Pearce’s questions and concerns here because they were completely lost in the night’s proceedings, but should be remembered:

- “Has any communications outreach been done to hotels of 50 rooms or less?”

- “Does this include bed-and-breakfasts and AirBnB?”

- “Why did this have to happen today?”

- “Are there legal concerns that having this vote, while we have WW out there, does this put us at risk [of appearing like] we’re trying to take a position on the measure?”

- “The language doesn’t cover subcontracted workers… Is there a reason for not including subcontracted workers?”

- “It leaves off notifications [i.e., visible signs] for guests [of the practice being implemented]…”

- “It omits the retaliation language to protect housekeepers whenever they do speak up.”

- “It leaves out hotel-workers’ ability for legal remedy if the law is not complied with.”

After Pearce finishes, Garcia chimes in to ask, “Do you want to [have those questions answered] now?” Pearce, off mic, adamantly nods, as if to say, “Of course.” Why on Earth would she ask questions now if she wanted them answered later?

Afterward, City Attorney Charles Parkin notes that the ordinance, if drafted and passed by the council, would apply in some specific ways that Measure WW would not, such as mandating panic buttons for hotels of less than 50 rooms; yet in other ways, as noted by Pearce, it would have less application than Measure WW. During Parkin’s subsequent answering of some of Pearce’s questions, Garcia again interrupts to attempt to clarify the laws surrounding the motion himself (7:27:22), even though he was not the maker of the motion and is not the city attorney. Though perhaps well-meaning, the confused series of interruptions distracted a bit from the force of Pearce’s questions.

Eventually, the maker of the motion, Price, takes the floor and claims she “doesn’t understand the basis of the opposition” to the motion. To the extent this is a true statement, it is frightening. To the extent it is a false statement, it is frightening. She continues, “I’m totally amenable to any recommendations my colleagues want to make.” (7:36:40)

In my time watching city council, I have never seen Price so… amenable. Her offer to simply let her colleagues more-or-less have their way with the motion is evidence that simply getting it passed that night, in almost any form, was all that mattered. Questions of effectiveness, intent, process, impact, timing, educating the public, misunderstandings—the usual litany of concerns Price pointedly brings to council each and every week—for some reason here, now, at 1 in the morning on Sept. 5, have no bearing. Councilmember Lena Gonzalez (CD-1) draws attention to this contradiction in her first comments, noting that Price’s claim that the motion has no fiscal impact is not only false, but also out of character.

Typically Price is very adamant that when giving something up, she get something in return—this is, in-fact, part of why I personally have learned a lot from studying her tactics, and part of the reason she is a powerful advocate for her district. But in this instance it only makes her tactics that much more transparent.

Ethical concerns

Gonzalez enters and begins by saying she is struggling as well with the content and the process of the motion. She notes it was “submitted very late, on a Friday, on a holiday weekend, on the supplemental agenda.”

Aside from the shadiness of the immediate timing, there is also the larger frame, which contains a big midterm election in November, and which serves to only further confound the image:

“The timing seems very bad… It may look like it’s confusing voters, which we never want to do,” Gonzalez says. “It seems a bit unethical.” (7:40:50)

The councilmember then ends with a strong point on implementation: “We have a nuisance abatement policy… [so] people who are not even keeping up with the quality of life in their hotels, do we honestly think they’re going to add a panic button?”

Councilmember Roberto Uranga (CD-6) takes the floor next, and echoes Gonzalez’s concerns over the ordinance’s potential conflicts with Measure WW.

“[Her point] is one that really perturbs me,” Uranga says, “given that we have a ballot measure already coming before the voters, and we’re addressing pretty much the same issues here… what impact would that have…?”

After City Attorney Parkin addresses again some of the potential conflicts between the proposed ordinance and Measure WW, Uranga responds, “There might not be an ethical issue here, but it certainly doesn’t pass the smell test for me.” (7:48:04)

Clearing space for confusion

Let’s break from the footage for a moment. Some of the councilmembers on the wrong end of the evening’s set-up were consistently nicer than they needed to be—a testament to their decorum. My take is that the entire process of the motion, as well as the content of the motion itself, were both clearly unethical, if not outright petty. But I’m also not an elected official, and so a different decorum applies.

The best that could be said of the night’s steamroll “discussion” and “vote” is that the makers of the motion wanted to one-up the years of work Pearce and others have put into the myriad labor, race, and gender issues—not just panic buttons—intertwined with the tourism industry. Housekeepers have a dangerous job even beyond the risk of sexual assault, and bear with them the pains, scars, and stories to prove it. By flippantly passing the item right in front of Pearce’s face before the November ballot, the makers of the motion could say they got done in one weekend what others have been fighting towards for years. If that seems to you both petty and unethical, I’d say you’re right.

Worse yet, we could interpret the night as an incredibly uncouth attempt to hedge some bets. With the high likelihood of WW’s passage in less than two months, perhaps a jumbled-together ordinance implementing panic buttons could leave space for the narrative that the Long Beach City Council had already—in a stirring 5 – 0 vote—resolved the issue, and therefore a vote for WW on Nov. 6 would be redundant.

That narrative is already being taken advantage of by the California Hotel and Lodging Association. They released the following statement last Wednesday morning, about seven hours after the motion to draft the ordinance passed:

“The City Council’s proposed ordinance makes clear what the hotel industry in Long Beach has been doing and will continue to do: provide panic buttons for our employees, ensuring their overall safety,” said Lynn S. Mohrfeld, President and CEO, California Hotel & Lodging Association. “The Council’s well-thought-out decision will address all the safety concerns in Measure WW, be implemented more quickly and will apply to all hotels, without the burdensome and expensive work rules.” [emphasis added]

In a Q&A with Mayor Garcia published Sept. 10th, the Long Beach Business Journal (LBBJ) took advantage of the same line, asking him, “We understand that 18 of the 19 major hotels in the city have panic buttons for housekeepers. Do you think the measure that’s going to the ballot is needed, and do you think it will pass?” [emphasis added]

The conversation continues:

Tomisin Oluwole

Fragmented Reflection I, 2021

Acrylic on canvas panel

24 x 30 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

LBBJ: The ballot measure requires a hotel to provide 30 days advance notice if they want someone to work overtime. How do you determine 30 days in advance that you need somebody to work overtime?

Garcia: At the end of the day, the people of the city put this measure on the ballot. Regardless of how difficult we might find pieces of the ordinance –

LBBJ: But it is impossible.

Business journals are, of course, business-friendly, and so, to the extent you know what you’re getting when you open the fold, it’s hard to knock them for completely ignoring all distinctions between journalism and advertising—that’s what they exist to do. But that generous social allowance makes it all the more disappointing when on occasion they publish something that not even a business journal should publish. You can witness one such exhibit below.

All this hints at the larger strategy: agreeing to draft the ordinance now has minimal risk—since it is so narrow in focus, and involves no apparent concern for its efficacy—but the move has huge potential gains. If the issues surrounding Measure WW are themselves allowed to be narrowed in the public eye to merely a call for panic buttons, then the five councilmembers who passed the motion are heroes and Measure WW is unnecessary.

Assuming the Long Beach Business Journal is correct that 18 of 19 major hotels already have panic buttons, then the ordinance in the motion would wind up having no effect on them at all, instead bearing mostly upon small-time motels. This makes grandstanding over the tiny first step—in which five councilmembers stampede their way through a vote to have the city attorney draft an ordinance that may later be passed to near-zero effect while confusing voters, wasting time, disrespecting process, and alienating colleagues—all the more, well, petty.

And perhaps a bit unethical. While Price is right in believing the stories of housekeepers who have survived sexual assault, such a commitment surely mandates doing something more to protect them than what 18 of 19 major hotels have already been doing.

Maybe worst of all, however, is the damage this series of behaviors has done to the process. Price stated in multiple ways during the council meeting that, just this once, the process shouldn’t matter. But the process is all we have—and I don’t mean just this once. The process of how we collectively negotiate and decide; the process of including and informing instead of excluding and conspiring; the process of asking and changing and growing; the process of what we hope to one day call democracy—the process is what defines who we are; the process very much is the content.

Instead, the motion that passed in the early morning of Sept. 5 bruised like power politics does and is meant to, leaving a permanent mark on interpersonal and social relationships. There is no going back from an event like that. Power was wielded by the conspirators merely to prove that the power existed for them to wield—power was wielded for its own sake. On its face, then, the motion had nothing to do with women or rights or public safety.

Price vs. Richardson

On that exact point, I would like to return to our footage, as Richardson for the first time takes the floor on this item to ask a series of incisive questions. (7:53:30) Given that Price had already stated, “I’m totally amenable to any recommendations my colleagues want to make,” Richardson takes the opportunity to offer a friendly amendment:

“I’ve heard at least three people talk about the most critical [issue being] doing this at the same time as an open election that we just certified a couple weeks ago. So, my question to you is, are you willing to allow staff to do research… and then we begin the process of the ordinance once we have results from WW?”

“No, I’m not,” Price says firmly.

“Okay,” Richardson confirms, “then I’ll ask the rest of my questions… Mr. City Manager, when is the first time you saw this recommendation?”

“I saw it this morning,” City Manager Patrick West states.

Richardson then asks Price why the motion was brought in such a rushed manner. The councilmember defends the motion by appealing to a distinction: “What I would say is, highlighting the deficiencies in the process, that’s one approach, but I would ask that we focus on the content. Is the content objectionable?”

When Richardson is able to resume questioning, he asks Price again, “On this issue, does it matter to you to have consensus on the Council, or is this something that you’re very comfortable moving forward on a split vote?”

Price says that she would be comfortable with a split vote. Richardson asks next about outreach, and Price says while some outreach was done by “some of the councilmembers,” she suggests “we can phase in the implementation.” Though, if the implementation were to be phased in, wouldn’t that slightly defeat the purpose of rushing its drafting before the November elections to ensure immediate public safety? Unless of course rushing its drafting before the November elections has nothing to do with public safety.

“It’s not a very complicated issue,” Price then states. “Hotel-workers are afraid of being in a room with a customer, and a panic button would help them feel safer.”

“It’s a little more complex than that,” Richardson counters.

After a brief back-and-forth, he continues, “I think the fair thing to do is to be honest about the way this has been presented, on Labor Day weekend, no outreach or interest to reaching across the aisle to a member of the council who has been engaged in the issue—I mean, that would have gone a long way to help bring the council together. And then expressing, at the very beginning of this, that you’re not willing to talk timeline. I think this is more politically-motivated than an actual policy conversation.”

The cliff at the end of the evening

The conversation continued after Richardson’s foray, and multiple requests were made to amend the motion to give the council more time before passing it. But, with each attempt, the conspirators refused to budge. When the impending result became clear, the opponents of the motion, one-by-one, left the room.

“Can we hold off until we get the fiscal report?” Uranga asked.

“There’s no need for a delay,” Mungo replied. “We know that there’s going to be a fiscal impact.”

(The urgency was markedly different from the patience expressed 12 months ago when the council, in a 5 – 4 vote split the same way, rejected the ordinance that voters have now placed on the November ballot as Measure WW. During that meeting last September, Al Austin, who voted against the ordinance, infamously asked, “What’s going to be the difference between what’s happening today and thirty days from now?”)

After rejecting Uranga’s request, Mungo made a second reference to how late it was, and asked that the question before the dais be voted on.

At that point, Councilmember Pearce left the room. (8:30:53)

After her, Councilmember Gonzalez left the room. (8:31:11)

Richardson reentered the conversation to clarify in a back-and-forth with Mungo that there would be no outreach done on this until after the election.

During that exchange, Councilmember Uranga left the room. (8:34:28)

Price then took the floor to say the item also served to affirm, in a very public and unambiguous way, that she cares about the safety of women, and that she did not appreciate people insinuating otherwise during past meetings where these issues were being discussed. (8:35:11) She requested of Richardson, “Put yourself in someone else’s shoes,” apparently referring to herself and her belief that she has been misunderstood by the public and neglected by her colleagues. The whole comment should be listened to in context for better understanding.

After Price finished, Councilmember Richardson left the room. (8:38:40)

Less than a minute later, the vote was held and the motion passed 5 – 0. In a flash that belies its actual time-span, the whole thing was suddenly done: the clock read over two in the morning, almost half the dais was empty, and there were only four members of the public left in the chambers—yet the room, the space, felt full of something very not right.

What had just happened?

Price snapped her fingers several times in quick succession to allude to how fast things could go now with only five councilmembers present. Yes, consensus is expedient—especially when defined as the absence of opposition. Just try not to fret too much about the process.

If you enjoy reading independent perspectives on issues affecting Long Beach, please consider supporting local grassroots media by subscribing to FORTHE.

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org