Rethinking Queer Intersectionality in Long Beach: Anti-Black Racism, Youth Struggles, and the Need for Change

12 minute readContent warning: This piece contains uncensored testimony that includes racial slurs.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of FORTHE Media.

The convergence of Black Lives Matter and Pride Month offers a moment of reflection for the queer community and a call to action for the mayor to defund the police. This article is the second in a two-part series.

CAN WHITE GAY PEOPLE IN LONG BEACH BE RACIST?

A White gay man was starting to act up in the crowd. Vanessa Romain went to go talk to him and calm him down. She was an organizer for Long Beach’s annual pride parade and was working security to help make sure the parade went by smoothly. Vanessa approached the unruly man and addressed him like she does with all her queer people, “Hey, my brother.”

“You’re not my fucking sister, you black bitch!”, he shouted at her. Hurt but determined to protect the event, Romain remembers, “I had to have him escorted off the site by the White police because he was so racist.”

Later she went to the top of the hill and just cried. She cried from the pain of broken trust. A gay man, who, by nature of their shared queerness, was supposed to be her brother, instead became her tormentor.

This one White gay man’s shouts were not the only incidents of aggression she experienced in the forty years she worked as an activist and community organizer in Long Beach. She has been spit on by White gay men. She has heard a friend tell stories of getting calls from other queers, who called “and told her to get ‘that nigger’ out of town.” And she and her friends have gotten more than their fair share of cold shoulders when entering gay spaces.

Most tellingly, racism has historically reared its head in the very space that queer people fought against police to create. Gay bars, often owned and operated by White people, carried their own form of policing to keep their space White and bourgeois. A common technique would be for a gay bar to direct its bouncer or bartenders to ask queer people of color to show multiple forms of IDs to be let in, echoing Jim Crow practices. In 1980, a group called Lesbians of Color picketed one such gay bar in Los Angeles in protest. Romain said some of her friends experienced this racist practice in gay bars around Long Beach, and so they would hold their own house parties to avoid unwelcoming environments.

Systemic racism is so entrenched in American society that anti-Black racism shows up in White, gay communities. As such, the White queer community is not immune to the calls to listen, learn, and deal with past and present racism.

IT’S TIME FOR “QUEER” TO GET INTERSECTIONAL

In the 1970s a group of Black feminists and lesbians formed the Combahee River Collective. The Collective worked to address the racism within a mostly White feminist movement and the sexism and homophobia in the Black Civil Rights Movement. The Combahee River Collective Statement declares: “We also often find it difficult to separate race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously.” The Collective tried to educate people to understand that essentializing one aspect of a person’s identity, in this case being “female,” obfuscated the important diversity that existed within that identity.

Later, in the 1980s, UCLA legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw put forward the term “intersectionality,” to encapsulate the experience of underrepresented folks. Intersectionality helps explain the struggles of identity politics for people on the margins who experience the intersection of various forms of oppression. It is a term that is widely used today.

As the queer community evolves to become more inclusive of all types of sexualities and identities, its singular focus on queerness inhibits the intersection of race and class and limits discussion on how queer people of color experience multiple systems of oppression.

The anthology Black Queer Studies is one site of entry for critical analysis. University of Virginia professor Marlon B. Ross considers the limitations of theorists like Michel Foucault by naming their contributions as “(white) queer theory.” Northwestern University professor Patrick Johnson resists the term “queer” by replacing it with “quare,” the way his grandmother would say queer in her “thick, black, southern dialect.” These theorists, in essence, argue that it’s time for an intersectional understanding of queerness.

University of Chicago professor Cathy Cohen explains this by way of personal example in her essay in Black Queer Studies: “Because of my multiple identities, which locate me and other ‘queer’ people of color at the margins in this country, my material advancement, my physical protection, and my emotional well-being are constantly threatened.”

The constant threat that Cohen describes is not one that White queer people with financial security feel. Yet it is the reality of many queer people of color and the Black Lives Matter movement calls on us to listen and understand.

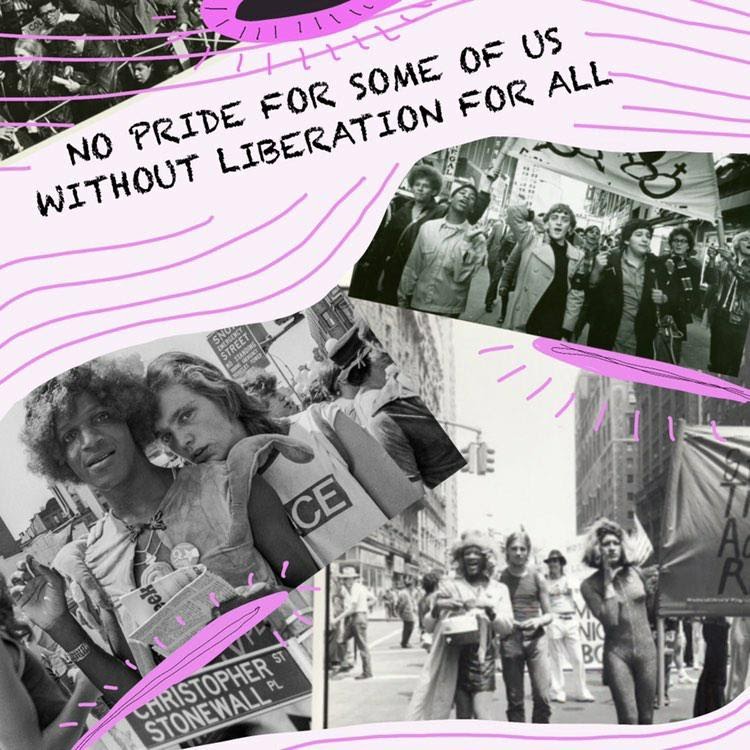

Breaking down the identity of “queer” and expanding our understanding of queer peoples’ experiences can lead towards desired equity. Perhaps one of the first steps is to relearn the past and undo the violence against the Black queer community created by the whitewashing of the Stonewall Riots.

QUEER HISTORY, WHITE MEMORY

Around 1:20 a.m., the cops entered the bar. The lights went on and there was confusion on the dance floor, where drag queens had been dancing to Stevie Wonder. The cops blocked the entrance and started shoving the patrons into a line, only allowing people to exit after they showed their IDs. Transgender folks and butch lesbians resisted, talking back to the police, intentionally uncompliant.

There was no foreseeable reason why this early morning raid on the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969, would be more than routine work for the police. It was at least the second raid that week. The meticulously researched book, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution by David Carter, recounts the events of that night. As Carter describes, in previous raids those let go would disperse, but this night they remained outside the bar, waiting to see what would happen. When the cops brought out one butch lesbian resisting arrest, they pushed her towards the paddy car and she yelled to the crowd, “Why don’t you guys do something!?”

Tomisin Oluwole

Face the Music, 2022

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 36 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

As Carter and others correctly show, the main people who fought back against the police were not the White, rich gay men who have most historically benefited from the gay rights movement. Instead, “all available evidence leads us to conclude that the Stonewall Riots were instigated and led by the most despised and marginal elements of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and [transgender] community.”

However, their actions have been whitewashed, most recently in the 2015 movie Stonewall, produced by White men and directed by Roland Emmerich, a White gay man

In Emmerich’s portrayal of the riots, it is the protagonist, a blond and heteronormative boy named Danny, who throws the first brick and starts the riot. The community quickly denounced Emmerich’s choices. As a Los Angeles Times review described, “This choice, some say, effectively back-burners the lesbians, drag queens and trans women of color so fundamentally present that night.”

People have rightly pointed out for decades that Black and Latinx transgender and gender-non-conforming folks led the way, a point that has resurfaced during the current Black Lives Matter protests. Activists have elevated the legacies of Sylvia Riviera and Marsha P. Johnson to undo the whitewashing. Their legacies are important for the QPOC community they helped build and serve, but they were not the only ones. Stormé DeLarverie, Birdie Rivera, Sissy, Black Twiggy, Betsy Mae Kula (“kiss my ass”), and Zazu Nova also fought back. And there are countless more whose names were not recorded and whose photos were not taken.

Whitewashing of queer power has damaging effects. It erases names and it erases people. Erasure is painful and isolating. As Vanessa Romain remembers, just ordering a drink as a Black lesbian in gay bars was hard: “It was like you faded into the darkness of the walls, that’s how I felt… they just don’t see you, it felt like if you didn’t have money, you weren’t there.”

The opposite—visibility and representation—can be powerful and uplifting. Some of those who most need to see themselves represented are the city’s queer youth of color, who bravely struggle for acceptance amidst so many barriers to survival. As Romain sees it, navigating life as a queer person of color “is heavy, is life threatening for lots of people, but kids are just dying because they can’t take it.” To the queer youth of color she gives this piece of advice: “Keep your spirit, fight the real fight, and don’t get discouraged or distracted by the little shit, look at the bigger picture.”

QUEER YOUTH OF COLOR IN LONG BEACH

Antonio Lavermon and Joel Gemino run programs through The Center that provide services to the city’s youth, from high school students to 20-somethings. Gemino runs a daily program called Mentoring Youth Through Empowerment (MYTE). Of the roughly 220 students he sees, over three-fourths are youth of color and 20 percent identify primarily as Black. Gemino says his group focuses on an intersectional approach, highlighting how “our queer identities do not exist in a vacuum.” In Gemino’s experience, his students of color are more impacted by risk factors like unemployment, physical and mental health issues, and houselessness.

The Black Lives Matter movement calls for us to recognize the needs of our Black queer youth, a process that requires both listening and action. As Lavermon relates, if there is a resource that the youth need but isn’t provided, “then that means some more work needs to be done. If there’s a need that people have, then we need to make sure that they know and that we know that their voices and their words do matter.”

Some activists have been calling for the defunding of the LBPD. Executive Director Porter Gilberg says The Center supports defunding the police. This stance is partly informed by the interactions his staff have had during emergencies. If there is an emergency, many people, especially White folks, are taught from a young age to call 911. However, if someone comes into The Center with a higher need of care or an emergency, the staff first run through questions to discern the risk involved in calling the cops: Is the cop going to be trauma informed? Have they ever worked with youth with mental health needs? Is the cop going to threaten the youth at any time? Might the interaction with the officer trigger the youth?

“These questions come from a very real and very dark reality,” Gilberg says. The inability for the staff to be confident that calling the police will help LGBTQ youth in Long Beach is just one example of the need for the mayor to lead the city in defunding the police. On a bigger scale, Gilberg further notes, “the police department’s failures are symptomatic of our local city governments failures as well.”

A first step of support for both the queer and the Black community would be for Mayor Robert Garcia, who has received over half a million dollars from the Long Beach Police Officer’s Association, and the city councilmembers to take that money and invest it in programs that help our city’s youth.

AN EVOLVED SENSE OF PRIDE

Long Beach is generally known as a queer-friendly city. It has rainbow-painted crosswalks, rainbow flags hanging outside homes, a gay mayor, a large annual Pride parade, and a community resources hub in The LGBTQ Center Long Beach. Yet, the Black Lives Matter movement calls us to question this inclusivity, scrap back the rainbow gild, and see how the city’s queer community is not automatically a safe space for queer people of color.

The city’s organizations must reflect the diversity of the people. Gilberg believes that even The Center needs to listen, take stock, and correct its course. He takes responsibility for the fact that The Center’s board has no Black board members and is working to fix systemic problems for today and for the future.

An open letter by former employees of The Center to the Board of Directors, published today, calls for more. The letter asks the Board to both remove Gilberg due to experiences of racism and sexism within the workplace under his tenure, and to review its process of investigating complaints. The Center did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The experiences of former employees highlight the need for the White queer community to push back against complacency and work towards a truly inclusive future.

The anniversary of the Stonewall Riots forces us to reimagine what a collective, people-centered, and anti-corporate event can look like. This year, rather than a city-sponsored parade, Queer Pride 4 Black Lives and Black Lives Matter Long Beach are hosting a communal event Sunday, June 28 at Bixby Park that looks to uplift voices that have been overlooked in the past. The groups’ actions are a step towards reimagining what pride can look like, not a corporate-sponsored event led by a group that has lost its way.

To remember the Stonewall Riots is to remember that “the devil in the blue dress” is not a friend of the queer community, a fact that Garcia chooses to ignore every time he cashes a LBPOA check.

To honor our elders, the community must honor the collective, and the collective we honor is not the wealthy or solely the White. The Stonewall Riots were an uprising, where, as Carter puts it, “the most marginal groups of the gay community fought the hardest—and therefore risked the most.” They are the heroes to celebrate.

Lily Lucas lives in Long Beach and is interested in collaborating on local LGBTQ+ history, memory, and space. They received a PhD in US History from UC Davis. To keep the conversation going, please direct message them on Twitter or Instagram: @mxlilylucas.

lilyhodges@gmail.com

lilyhodges@gmail.com