Why Fund the Police?

5 minute readThe views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of FORTHE Media.

A month ago the group Queers Obliterating White Supremacy helped organize an event commemorating the Stonewall Riots. This event was a total re-imagination of what Long Beach Pride could look like. It successfully challenged the idea that things should remain the same because it is the way it has always been done. This article takes that ethos and applies it to the budgetary debates this month around the funding of the Long Beach Police Department.

Long Beach must pass its budget by the end of September, which means the city is braced for weeks of debate on an issue that the Black Lives Matter movement and the People’s Budget from Long Beach Forward have helped bring to the forefront: defunding the police.

For some, the concept of defunding the police is positive and inspiring. For others, it is a confusing concept that conjures up fear. Those with fear do not see why we should defund the police. Perhaps, then, it is helpful to flip the question on its head and ask: Why should we fund the police?

First, a quick breakdown of how the Long Beach budget works. The city’s fiscal year ends Sept. 30 and the budget must be passed before then. The city has various funds but only one that is completely discretionary—the general fund. So, when discussing the budget, people are usually referring to the general fund.

The general fund receives its revenue from taxes and fines paid by people who live and work in Long Beach. Property tax is the main source of revenue, but fines, such as parking tickets, also comprise a significant form of revenue. Currently, the general fund is used to fund the police, fire, library, parks, politicians’ salaries, disaster preparation, and public works services. To view the current fiscal year’s budget, click here. For some historical context, the past 15 years has seen around 45% of the general fund going to the police. In that same stretch of time, the budget for the library has remained at roughly 2.9%.

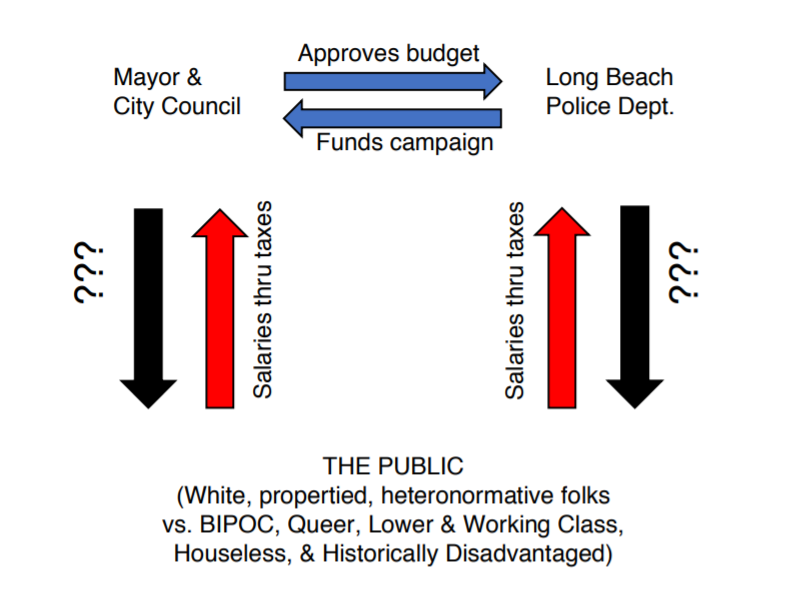

The police are paid for by the people. In theory, they work for the people, with almost half of the general fund, paid for by people’s taxes and fines, going to LBPD. A person’s level of comfort with the idea of funding the police tends to mirror their relationship with the status quo. The public’s relationship with the police and state apparatus, and the questions raised by it, can be visualized like this:

Tomisin Oluwole

Ode to Pink II, 2020

Acrylic and marker on paper

14 x 22 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

With money flowing upwards and then back and forth between those in power, it is helpful to understand the relationship between the public and the police as transactional. The question why fund the police? behooves us to consider, what is produced by funding the police? What do the people get in return?

The “state”—used here to mean local government—and the police both serve to uphold the status quo, which remains White, propertied, and heteronormative. For many living within the status quo, funding the police is a pragmatic step in maintaining the very society they benefit from. From this view, the police become protagonists in their journey to the sense of securing control over their lifestyle. In their transaction with the police, through taxes and fines paid to the general fund, the police produce a sense of security. As the recent impounds of non-Long Beach residents’ cars by the LBPD’s “Looting Task Force” shows, the lengths to which the police state is willing to go to provide a sense of security flirts with extralegal procedures.

In contrast, for those not squarely in a White, propertied, and heteronormative lifestyle, the product of the LBPD is not security, but pain. The LBPD antagonizes Black, Latinx, and queer folks, Cambodians and Filipinx, the restless young and the forgotten elderly, immigrants, the working class, and the houseless. For Black folks, even an act as common as riding a bike can become a moment for police harassment and legal consequences. The experience of the police and the state by those outside the status quo is an experience of the state and the police as peddlers in pain.

This pain takes many shapes. It can come from physical violence or psychological violence at the hands of the police. It can derive from, arguably, the worst kind of violence, which is the act of ignoring—refusing to see or hear or acknowledge—as is the case with the unsolved murder of Frederick Taft. The mayor and city council become complicit in peddling this pain by accepting donations from the Long Beach Police Officers Association.

Inherent in the people’s call for defunding the police is the call for reinvestment in the lives of BIPOC folks living in Long Beach and a call for the $265+ million given to the LBPD each year to be used for programs and services that can address many of the causes that lead to crime and inequity. Public safety does not have to be a euphemism for police control and domination.

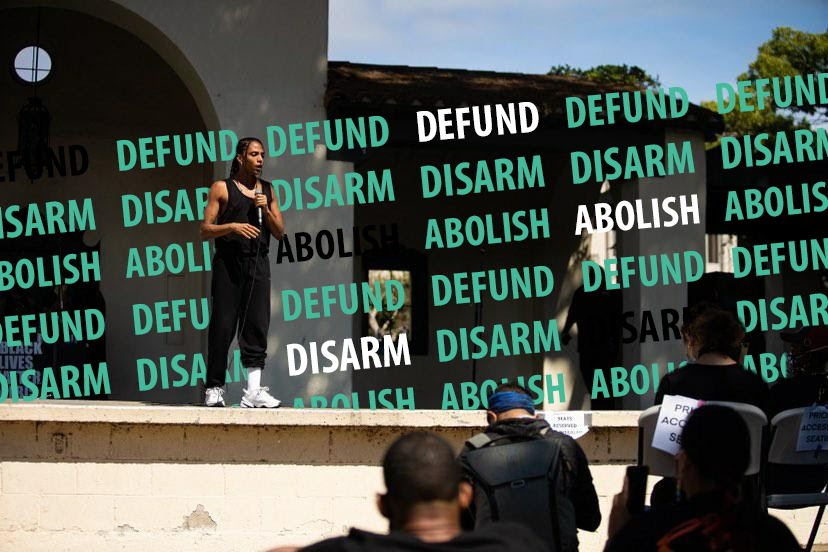

A month ago, the Stonewall Commemoration event at Bixby Park taught us that we can imagine a safer and healthier alternative. Activist Janaya Khan spoke at the event and discussed pain with the crowd. They asked the crowd to “be witness to each other’s pain” before a sign on the stage that read “defund, disarm, abolish.” They acknowledged pain’s existence to lead to a powerful call to action: “If you don’t use your pain, your pain will use you.”

By funding the police we fund the producers of our pain. In the end, why fund the police? is rhetorical. We do not have to fund the police. The imagination behind the idea that makes it seem like funding the police is a necessity, or a forgone conclusion, can be undone. We can find transformative alternatives to public safety. As Khan said, “our job is to imagine differently, and make it true.”

Lily Lucas lives in Long Beach and is interested in collaborating on local LGBTQ+ history, memory, and space. They received a PhD in US History from UC Davis. To keep the conversation going, please direct message them on Twitter or Instagram: @mxlilylucas.

lilyhodges@gmail.com

lilyhodges@gmail.com