“Restore the Facade”: Gentrification and Downtown’s New $215 Million Luxury High-Rise

by James Andrew Carroll | Published July 19, 2020 in Perspectives

47 minute readThe views expressed in this essay do not necessarily reflect the views of FORTHE Media.

The $215 million Broadway Block development is on its way. Long Beach’s newest megaproject will include five courtyards, several restaurants, office and creative spaces, and a number of structures—the largest being a luxury high-rise dotted with penthouses.

Once finished, it will stand atop the grave—between 3rd Street, Long Beach Boulevard, and Broadway—where the historic Acres of Books used bookstore had spent the last decade decomposing.

There will be 400 housing units in total. Back in 2016, there was talk that some of those units would be reserved for graduate students of Cal State Long Beach. That number eventually settled at 14 units, according to the city. Then, as the Long Beach Post reported just this past week, the project switched ownership due to economic setbacks related to COVID-19, and so even the modest 14 units have now been scratched.

The ownership change sent the development from Ratkovich Properties to Onni, meaning we’ve gone from a corporate owner that doesn’t give a damn about how high your rent is, to another corporate owner that doesn’t give a damn about how high your rent is.

The Post article overstates this difference—mainly by claiming CSULB is losing “over 100” units, when it is only losing 14; but also by characterizing the previous developer as “local,” when they are based in Irvine. As a result, the article also overstates the loss to the city in this change.

The real losses, however, started years earlier, and continue to pile up, even as local media outlets continue to ignore them. The history of the Broadway Block development mirrors the history of the hubris of city leadership and its disregard for Long Beach residents—a story the recent change of the project’s ownership only adds to.

So I won’t be making a big scene in this essay about the 14 units. Nor will I spend any more time than what you’ve just experienced addressing the change of ownership. The real story here is what the project’s history can teach us about this city’s backwards priorities.

The best way to approach that, in my opinion, is to talk about the development from a few different angles, with the goal being to politicize each of those angles as much as possible. Gentrification often works by depoliticizing all of its various moving parts. One company owns the project. Another company designs it. Some other person helps boot the existing tenants out of the way. All of City Council votes to pass the project without so much as a question. A few commissions approve the project in some hearings, during one of which a member has to recuse themselves because they are one of the principal developers. (pg. 4) A few journalists write some boring articles about the brand new building coming to town. Next thing you know, Long Beach has a luxury high-rise with zero affordable units in the middle of its downtown and somehow no one is to blame.

So we’ll politicize the Broadway Block’s intersection with six separate categories, each bearing its own relationship to the gentrification of Long Beach. You can click the highlighted text to scroll to that section, and read whichever one looks most interesting first, or simply read them all in the order presented:

- the tragic history of Acres of Books as it struggled against city leadership;

- the language the Broadway Block’s architect uses to hype the project;

- the wasted power of Long Beach’s Cultural Heritage Commission;

- the issue of housing affordability downtown;

- the role Long Beach media outlets play as megaphones for developer interests;

- and, lastly, our society’s problematic notions of progress.

“But it’s hard to imagine how a new address and some money will adequately compensate anyone for the loss of a one-of-a-kind dusty barn of a place, where for 47 years ordinary people like you and me… worshipped the printed word.”

– Journalist Theo Douglas, discussing the potential closing of Acres of Books in 2007.

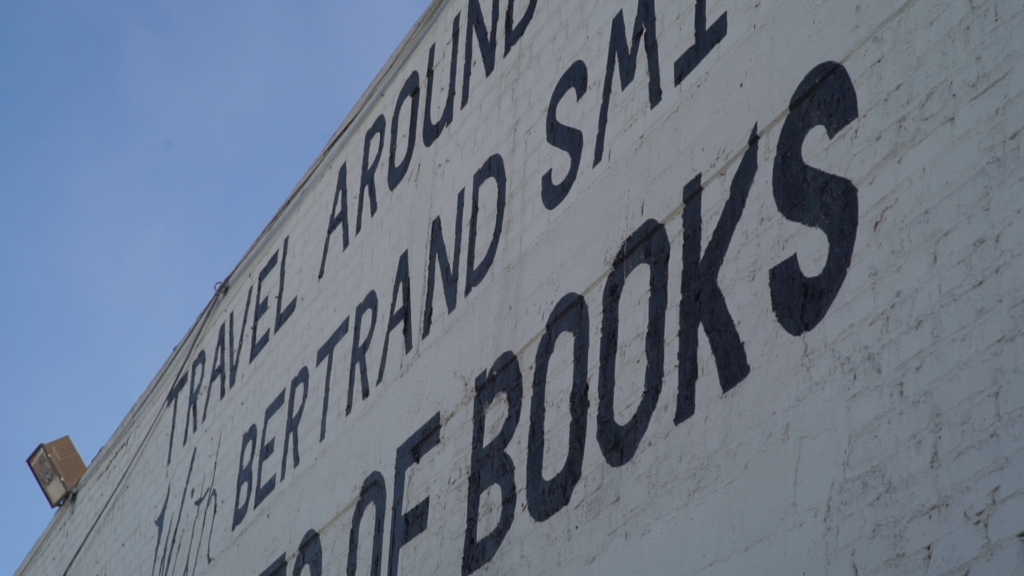

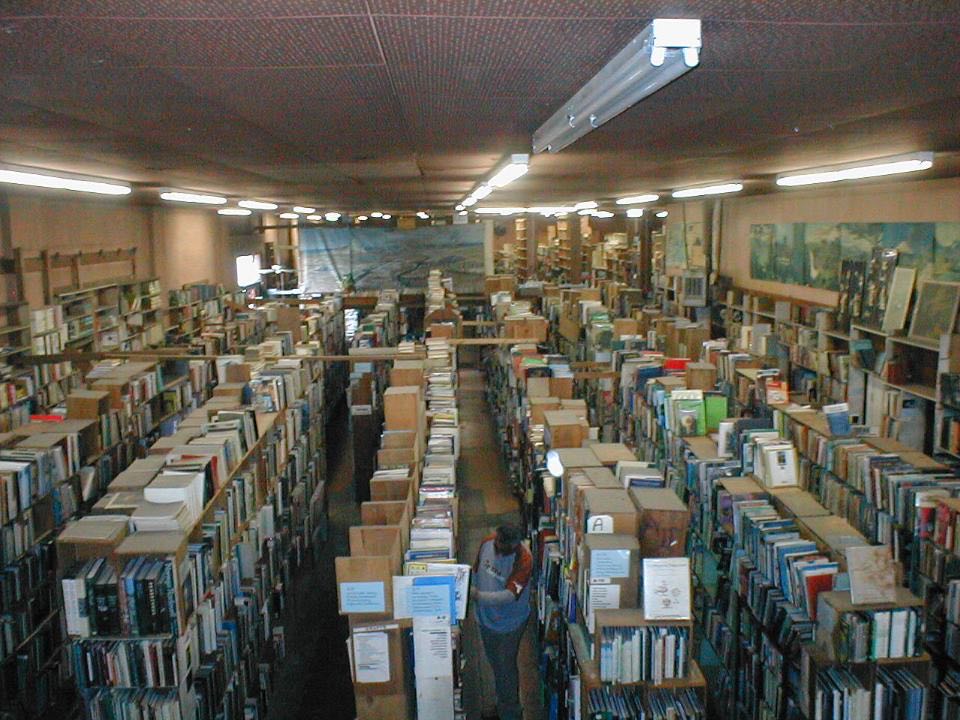

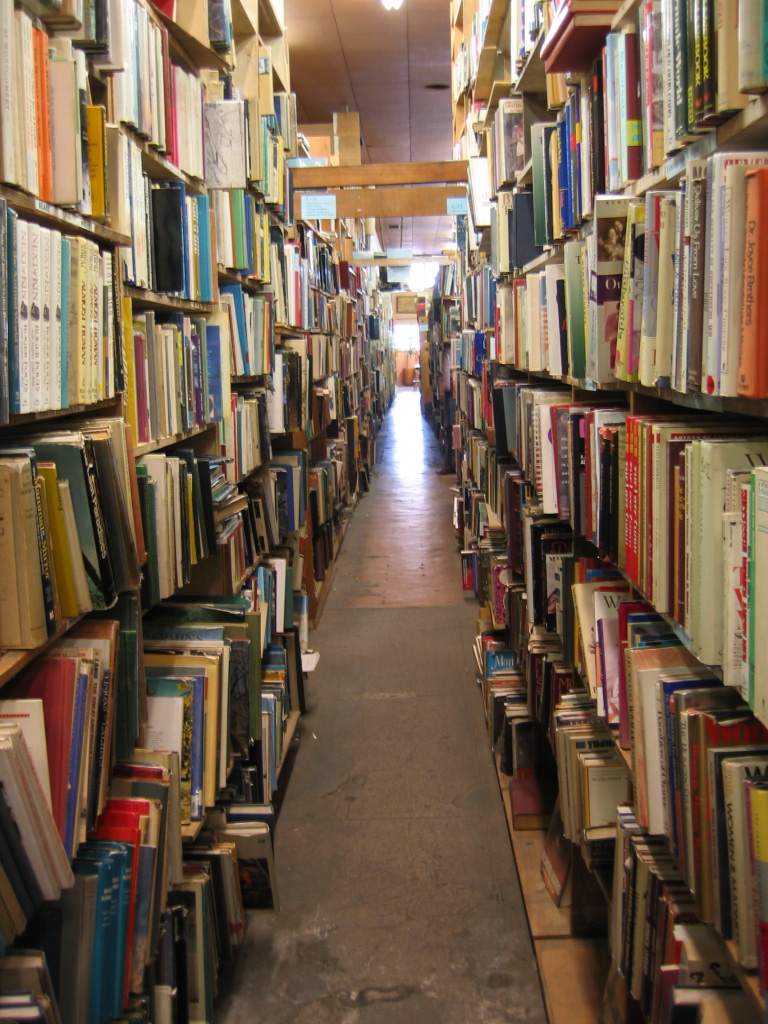

Acres of Books was a world-famous used bookstore that, from 1934 to 2008, called Long Beach home. At one point, it claimed to have over one million books lining its endless alleys, and, after it closed, all that remained for 11 years was an empty building, its northern wall adorned with an iconic, suddenly fruitless, invitation:

“Travel around the world with Bertrand Smith’s Acres of Books”

Half a century earlier, Bertrand Smith, the original owner of Acres of Books, was working to ensure the bookstore’s invitation meant something. He established an endowment of $20,000 (in 2020 dollars, that would be over $175,000) to “finance an annual lecture … and provide for the purchase of rare books…”

The very first lecture took place on April 10, 1959, and was given by renowned American librarian, and former UCLA University Librarian, Lawrence Clark Powell. Powell, noting that Smith’s endowment had enabled rare books to enter the Long Beach public library collection, concluded his lecture with pride:

“Those of you who lack time and purse for personal book-hunting have your public library as a kind of non-denominational temple which you can enter day and night. The kind of enrichment it is experiencing from donations such as Bertrand Smith’s is a cultural infusion into the veins of all of you. This is good health for the mind and the emotions. And thus I end on a note of gratitude to your city librarian and your city bookseller, joined in a bookish alliance whose results will be more lasting and precious than oil.”

Just one year after the donation of rare books to the city library, the city thanked Acres of Books by forcing the store to move locations. Its original Long Beach address—140 Pacific Avenue—was needed by the city, not quite for something as precious as oil, but for a parking lot.

Still, a few years later, Smith donated even more books to the city, including “a two volume facsimile of the Gutenberg Bible.”

Despite such priceless gifts, various city schemes and development plans would take priority over the existence of Acres of Books again and again. In the 1980s, for instance, after it had already moved a few blocks east to make space for that parking lot, the plan was then to replace the bookstore with office towers and townhomes. Theo Douglas, journalist for former Long Beach alternative weekly, The District, described the development thus:

In 1982, the earliest date city archives mention erasing Acres of Books from Long Beach Boulevard, the city’s dream was to let the Urban Pacific Development Corporation build a $90 million, “double” 15-story office complex on that block “with 92 townhomes.”

Douglas interviewed Smith’s granddaughter-in-law, Jacqueline Smith, who was by then the owner of the store, as she continued the family struggle to protect Acres of Books from the city:

“They told us we had to move in 1986 and we even prepared for it, and it never happened. That was when they built that first fiasco,” Smith says, meaning Long Beach Plaza. “My father-in-law was in charge then. But the economy went down, and I think that was why they didn’t build it. I hope the economy doesn’t go down, but I hope we get to stay. It’s my dream [to run a book store]. It always has been.”

By 1990, the city was just trying to get Acres of Books out of the way for redevelopment however it could. Susan Schick, former Redevelopment Agency (RDA) Director, said at the time:

“My point has always been that if the goal of the community is to preserve Acres of Books, you’re not going to do it by preserving the building.”

Finally, by 2007, the RDA had finished buying up all the buildings adjacent to Acres of Books, in preparation for what the city was now calling the “Broadway Block,” and so the bookstore was the last thing standing in their way. Former Second District Councilmember, Suja Lowenthal, trying to hurry along the bookstore’s departure, had been quoted the year prior saying, “I’m eagerly looking forward to [the block’s] development.”

Indeed, an RDA press release announcing the impending bulldozing of the other buildings at the site, claimed Lowenthal “will lead the… demolition”—which I can only assume to mean she quite literally marched in front of a row of bulldozers, parading to the rhythm of drums and the melody of bugles, and, upon shouting “Charge!”, took a pick-axe to the One-Stop Office Furniture Store while the cavalry lent support from the rear.

Local muckraking outlet, LBReport.com, recalled what happened next:

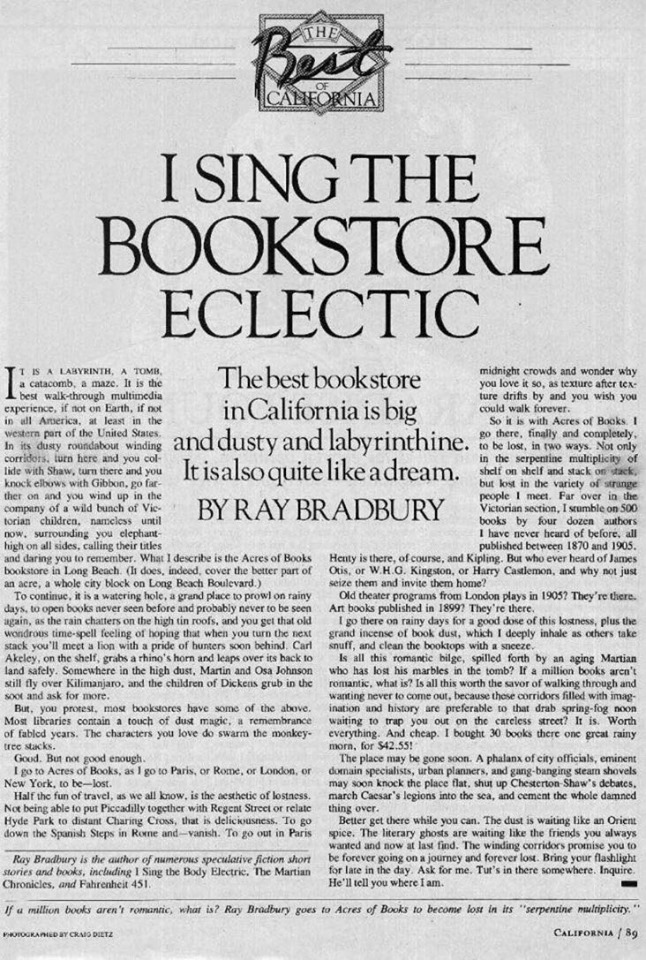

“Although wheelchair bound by June 2008, [American writer Ray] Bradbury traveled to Long Beach to plead with LB officialdom not to destroy Acres of Books… and suggested it should be the centerpiece of the new development. The press and public came to hear what he had to say but LB city officials were invisible; to our knowledge they didn’t meet with him.”

Later that year, surrounded by the destruction of their former neighbors, and with the pleas of even a famous novelist having no visible effect, the owners of Acres of Books finally agreed to sell the building to the Redevelopment Agency. Smith was quoted in the L.A. Times:

“I think it’s very sad … But it’s part of the ongoing culture and the changes with what people do in their free time … but also the rents, the redevelopment, the profit margins, it all just contributes.”

The bookstore’s manager, Raun Yankovich, was also saddened, calling the closure “a tragedy”:

“It’s more than a bookstore … It’s a place where the written word has a magical quality to it.”

The city’s position, of course, was a bit different. Craig Beck—now Long Beach’s Director of Public Works, then Executive Director of the RDA—said he was “pleased” with the sale, and noted:

“The property is part of our Broadway Block project, which will celebrate the arts…”

It seems strange, selfish, and a tad inhuman to claim you are “pleased” with a sale when the folks affected on the other side of the transaction are calling it “a tragedy,” and are expressing concerns about “the rents, the redevelopment, the profit margins…”

I am also honestly unsure how a $215 million project that is going to make it even more difficult for artists to afford the East Village “Arts” District, and which required bulldozing a bookstore, is going to “celebrate the arts.” As LBReport phrased it:

“One might suppose that a humongous homegrown one-of-a-kind independent bookstore might have been a very smart centerpiece that could attract and serve CSULB students (and others) in downtown LB. But LB city officialdom had other plans … and a bookstore wasn’t among them.”

A year later, the RDA listed as an “accomplishment” that it had, “assembled [the] Broadway Block through acquisition of property and relocation of occupants to prepare the site for development.” Yet after the 2008 sale, and for the next 11 years, the building simply stood there, empty. As of this writing, there is still nothing there. Photos taken recently, highlighted throughout this essay, show only a giant ditch in the earth. The owners of Acres of Books had been more-or-less forced to give up their property, their business, our bookstore, for no conceivable reason.

During this decade-plus dormancy, a lot changed: the redevelopment agencies across California were all shut down, and their properties sold off to developers; Lowenthal became the city manager of Hermosa Beach; Beck became Long Beach’s Director of Public Works, and then retired; the District weekly closed shop, apparently after it was “beset by several advertising boycotts by local merchants, frustrated by the bright light of its coverage;” the ownership of the project changed just as construction was getting started; and, of course, the entire global economy collapsed… twice.

What exactly was the point of it all? What did we win? What is there left to win?

It turns out that no matter when you ask the question, the continued existence of Acres of Books has never been part of the plan. It has been threatened, in turn, by parking lots, office towers, councilmembers, city managers, developers—by whatever project we happened at the time to think was more important than a bookstore—and after over half a century of bearing the weight of all our greed, it has finally collapsed.

“The Broadway Block … is envisioned as a place that connects people to purpose and transforms space into place.”

– Description of the development from the architect’s website.

We have been told since we were children not to judge books by their cover, and yet all that remains of the bookstore today is the only thing the gentrifiers have ever deemed worth saving: its cover.

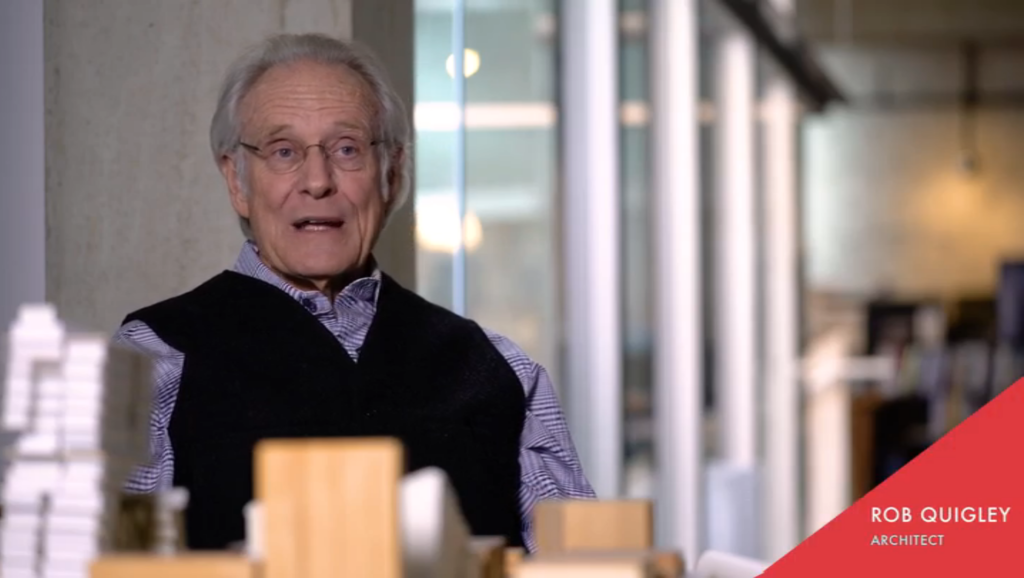

The opening archway of Acres of Books has, through all this conflict, retained its historical status. Thus, when the project finally began digging up earth last December, its first hoorah of bulldozers eradicated the other walls—including the northern invitation for readers to travel the world—but made sure to leave the facade untouched. In a video released on his personal website, the architect of the Broadway Block, Robert Quigley, informs us of the plan:

“What we’re going to do is restore the facade…”

The word “facade” comes to us through the French “façade,” via the Italian “facciata”—both of which mean “the front of a building,” deriving from the Latin “facia,” meaning “face.” Its first figurative use as “an outward appearance meant to conceal a less pleasant reality,” is cited to at least 1845.

Partly because the technical use of the word within architecture predates its use as a metaphor for deceit, the word “facade” is still used today to mean, quite plainly, “the front of a building;” and, thanks to this duplicity, the critical among us are gifted some dark and ironic phrases from the harbingers of gentrification when they discuss a building and say something simple—like “restore the facade”—unaware that they also sound so sinister.

Are we restoring “the front of a building”? Or are we restoring “an outward appearance meant to conceal a less pleasant reality”?

The second meaning of facade—deceit—thus turns the restoration of a building’s face into a mask, meant to conceal the damage the project is doing to the city. With this latter interpretation in mind, one squirms a bit when Quigley continues:

“We’ll then remove the skin…”

That is an uncomfortably human metaphor for discussing a wall… but perhaps in that way it reveals further the image-focused lens of our economy: how we prioritize our shallow perception of the image of a building over that building’s actual impact on the lives of human beings; how we imagine that historic preservation is a process only of cosmetics; how we value flesh above everything that is, after all, beneath it.

“Remove the skin” also frightens me, with its aroused yet clinical tone, and suggests a world-view of doctored appearances. In my time working on this essay—whether speaking to residents in the East Village “Arts” District about gentrification, or researching various elements of the project’s history, or reading comments from concerned residents online—the word that continued popping up to describe the burgeoning development of Long Beach’s downtown was “sterile.”

Seen this way—in the glare of hospital lighting—the doctor is the gentrifier and the sickness is the neighborhood. Thus, no matter how beautifully the surgery is done, it simply begs the more fundamental question: to what extent is our understanding of aesthetics steeped in the dictionary of economic domination?

To take just a few entries from Quigley’s dictionary, we can return to the architect’s personal website to learn first how he defines “urban responsibility”:

“The Broadway Block project has an important urban responsibility. It must help shape and respect Long Beach Blvd, and then transition to the four story structures on Elm Street.”

By the admission of its architect’s own words, the “urban responsibility” of the Broadway Block project has no perceivable connection to the lived experiences of human people who inhabit the area—let alone their right to continue inhabiting the area—but merely exists to ensure that some semblance of the appearance of the neighborhood is maintained.

It is through a similarly shallow understanding of the phrase, “mixed use,” that the architect of the Broadway Block can unironically say:

“A lot of projects say they’re mixed use—but this one really is mixed use.”

Again, that can only be true if by “mixed use” we mean any place where rich folk can frolic guilt-free on the first floor, and then take the elevator to pass out cozily on the 10th.

Sure enough, Quigley continues by describing the high-rise structure of the project as containing “penthouses that are not just at the top, but also at the lower levels to try and energize the entire building.” In the quantum physics of luxury design, penthouses can apparently be both at the top floor, and also at any other conceivable floor. Though one has to ask: if no one lives there, do they still exist?

“They will retain the historic front facade. They will bring it back to life.”

– Comments from the Cultural Heritage Commission at the Commission’s November, 2017 meeting.

The abuse of language by bureaucrats and capitalists clearly takes all sorts of wicked forms, typically presented as very matter-of-fact, but which consistently belie their responsibilities in the world.

As another example of this, Long Beach has a Cultural Heritage Commission, but, somehow, “Cultural Heritage” has no connection to the things one might hope—like, say, books, or long-time tenants.

Instead, the commission solely occupies itself with maintaining paint schemes, original building materials, signage, columns—all the outward appearances meant to conceal the less pleasant realities of displacement, eviction, greedy landlords, developers…

When I wrote last year of this city’s powerful NIMBY class, I touched on this same subject in another way:

Tomisin Oluwole

Ode to Pink II, 2020

Acrylic and marker on paper

14 x 22 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

“And let’s talk about architecture for a second. It says a lot to me that it is easier to have a neighborhood deemed “historic,” and therefore worthy of protection, than it is to have the people of that neighborhood deemed “historic,” and therefore worthy of protection …

The reason for this … is that historical preservation has nothing to do with the abstract idea of the past, even though that is how it is presented to us. Rather, it has entirely to do with the concrete reality of political power, and who does and does not have it.”

This is why the “Cultural Heritage” Commission doesn’t hold meetings about seniors getting priced out of their units—even though seniors, in my estimation, would certainly be part of our cultural heritage.

This is why the “Cultural Heritage” Commission doesn’t hold meetings discussing whether or not to approve the mass displacement of all people living in a building so the landlord can turn the place into a boutique hotel—even though removing at once all people from a building, and sending them packing to disparate locations, would certainly have an impact on cultural heritage.

That’s not to say the “Cultural Heritage” Commission won’t have meetings about the buildings these people inhabit. It’s just that, at these meetings, the Commission will do all it can to ensure the cute transom windows aren’t touched.

So, yes, of course the “Cultural Heritage” Commission had a meeting about Acres of Books and the Broadway Block. In the documents produced in 2017 for the meeting, the word “books” was not once mentioned in reference to the physical objects that contain the literal elements that constitute cultural heritage. Instead, the word “books” alone appeared as part of “Acres of Books.”

It seems to me we can go a bit further then, and say that in the language of the “Cultural Heritage” Commission—in the language of Robert Quigley, in the language of gentrification—“Acres of Books” is not the name of a bookstore that contained at one point over one million books. Rather, it is just the name of a facade, and, to our children’s children, that’s what “Acres of Books” will become.

Before the switch to Onni, the previous developer’s president, Cliff Ratkovich, told the L.A. Business Journal:

“It’s a building that has some historical significance with a historic facade. We want to repurpose it with food uses, with restaurants and a food hall.”

With any luck, it will be named the “Ray Bradbury Food Hall,” and the restaurants there will have novel-themed cocktails and Brussels sprouts with a flaming Fahrenheit 451 sauce. Anything to preserve our cultural heritage.

“Integration of the historic Acres of Books property … supporting cultural and retail opportunities that create a collaborative urban fabric …”

– A 2016 city recommendation for the Broadway Block.

Back in 2016, a recommendation approving the Broadway Block project from city staff stated:

“The development concept submitted by the Buyer/Developer for the [Broadway Block] envisions a seven story residential structure containing 141 units including student housing.”

Nowhere in the recommendation is there any concrete information on what exactly that means, or on how many of the units were going to be affordable. Seemingly, only some of the 141 units in the seven-story part of the project were maybe, perhaps, who knows, going to be affordable—and even then only for a specific segment of the population. According to the city, the Broadway Block had eventually designated a tiny 14 of its 400 units (3.4 percent) as “affordable units for professors and graduate students of California State University, Long Beach.”

But there would have been a few immediate concerns with even that.

First, as far as those most in need of affordable units, should “professors and graduate students” get priority over the countless other groups we could list here? Many working class students and non-collegiate learners—groups who would probably most appreciate, say, a used bookstore—are going to see their rents increased as a direct result of this project.

And, second, if it was learning and education we cared about, then who would honestly accept 14 units for graduate students as a substitute for acres of cheap, used books? After all, the Broadway Block’s high-rise of unaffordable units will be erected in the center of a downtown area which has historically had incomes well below the medians of the rest of Long Beach, the county of Los Angeles, the state of California, and the whole United States.

Now that the student housing has been eliminated completely, we are left to see even more clearly what was there to be seen all along: this project doesn’t care about the city or its residents.

The new owner, Onni, has already come under scrutiny for building so much in Downtown Los Angeles without including any affordable units. But it’s not as if the previous owner was building affordable units anywhere, either. Ratkovich Properties had already developed the Edison in Long Beach, for instance, which is described on the project’s website as consisting of “156 luxury flats.”

So why wasn’t an affordable developer given priority for this project? Especially when it was replacing, of all things, a used bookstore? The following list of the project’s bidders was obtained by FORTHE journalist Kevin Flores several years ago via a public records request:

The affordable housing developer, Bridge Housing, is listed up top; and there is even a properly “local” developer, Skyline, at the bottom. It is unknown why they were turned down.

Instead, the bid went to Ratkovich Properties, pointing once again to the explicit plan of city leadership: replace long-time, low-income residents with a wealthier demographic. They set the stage quite neatly for this result years earlier, in 2012, with the passage of the Downtown Plan.

Though I’ve written about the Downtown Plan before, I’ll do it again, because it deserves more attention, and more criticism. The plan fast-tracked new developments, and included no provisions for affordability, nor any measures to prevent displacement. Elected officials knew mass displacement was on its way, and not only did nothing to stop it, but actively showed unknown numbers of families the door. These realities forced the city’s own draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the Downtown Plan to conclude, “the impact of implementing the Downtown Plan would cause significant and unavoidable adverse environmental impacts in terms of loss or displacement of existing housing units.”

Keep in mind that Mayor Robert Garcia was a councilmember in 2012 when the Downtown Plan was passed, and despite the aforementioned draft EIR noting the “significant and unavoidable” adverse impacts it would have on housing, and despite a report which warned of displacement (pg. 1) and suggested an inclusionary zoning provision be included (pg. 4), and despite attempts by other councilmembers to add affordability provisions, Garcia ignored all of the above and “spearheaded moving the Plan forward as-is.”

This power-grab actively benefited wealthy developers at the direct expense of Long Beach’s most marginalized communities. Data consistently shows that people of color are disproportionately housing cost-burdened in this city (pg. 7), and thus much more likely to face a range of housing issues, including displacement. Since the Downtown Plan was passed, landlords and developers have evicted unknown numbers of Black and Brown working-class families, whose experiences have been erased as much as their homes have been taken from them.

As if on cue, here again is the president of Ratkovich Properties—the former developer of the project—celebrating the takeover:

“According to Cliff [Ratkovich], 70% of new Downtown residents earn $50k to $100k per year, and an additional 20% pull down $100k to $150k.” [emphasis added]

Clearly the project expects, and demands, much wealthier residents. Far from supporting the lives of local artists or students, the Broadway Block will make their existence here that much more precarious.

“Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia has often shined a spotlight on the amount of development occurring throughout the city, particularly in downtown, stating that the city is “booming” – and it’s easy to see why.”

– Coverage of downtown development from the Long Beach Business Journal.

The media landscape in this city is dominated by ad revenue from local businesses and corporate ownership by local developers. Perhaps as a result, journalists seem to think it’s their job to tell us all the nice things developers have to say about their own developments, instead of getting under their skin, and tearing away the facade.

Article after article rolls out the welcome mat for rich white developers like Ratkovich, while completely ignoring the fact that Long Beach is building a luxury high-rise on the grave of an old bookstore in the middle of a diverse and rent-squeezed downtown.

Most coverage of the Broadway Block project uncontroversially doles out basic information, as though there was nothing much else worth discussing. Though sometimes the coverage goes a bit further, and becomes an unquestioning platform for praise by city officials. Other times, it acts as a megaphone for developers. Everywhere, the perspectives of city officials or developers are included, and, each time, their quotes are simply regurgitated for the reader as gospel.

The only hint of controversy you would get from reading the coverage in this city is, of course, concerns about parking. In case you’re wondering, I chose not to talk about parking in this essay because while Long Beach already has parking requirements, it doesn’t have working-class people requirements.

Still, the most egregious example of coverage comes from Brian Addison at the Long Beach Post. He manages to do everything listed above in just a few hundred words: regurgitate developer quotes, assure the public about parking, dole out basic information, and avoid any hint of controversy.

In fact, his article accomplished all of this in such an effective manner, that Ratkovich Properties apparently felt obliged to share the piece on their company website. Why pay for a press release when local journalists are already writing like brand ambassadors?

One particular paragraph from the article stuck out to me more than anything else I read, and it fits into our theme of gentrification prioritizing the cover, the skin, the cosmetic, the facade, over the actual lived experiences of existing residents.

To start, the author maintains a very professional tone, only sticking to the facts, in that sort of way our societal narrative of journalists says they should. That’s what makes it so surprising to get near the end and find this snarky, out-of-place paragraph:

“The most recent renderings show the geometric rooftop of the pyramid-like façade of the southwest corner, mirrored squares that permit the plebeians to look up toward swimmers with jealousy and a sense of voyeurism, and a sea of mostly white folks. (Please work on that, renderers.)”

Are we supposed to gloss some sentiment of solidarity in this? The effect is exactly the opposite. Like performative politics generally, such a remark is rendered inauthentic in direct relation to its innocuousness. Who is this paragraph meant to hold to account? The nameless graphic designers? The people who are in charge of generating stock photos? What is at stake here? What has the author risked?

The situation is at least made slightly comical, however, when you consider that the author also published an article in June 2019 on the same subject, and another one way back in 2017, with many of the same phrases, and which both included, word-for-word, the same sly shot at our villainous “renderers.”

Stock white images are annoying, sure—but what about stock white journalism? Somehow, the author takes three different opportunities to point out the perceived racial discrepancies, not of the gentrification embodied so superbly by the Broadway Block, but of one rather meaningless, artificial image accompanying it.

And yet, are there actually any racial discrepancies in the image? Won’t the Broadway Block’s inhabitants end up being “a sea of mostly white folks”?

Although all the articles linked in this section show some of these same blindspots, the Post’s coverage is the most consistently problematic. They provide a clear example of how media models which are structured around the interests of developers and land speculators, tend to produce content that supports gentrification.

The Post is owned by Pacific Communities Media (PCM), which also recently purchased the Long Beach Business Journal. PCM is a subsidiary of Pacific6, which has its hands in downtown development.

One of Pacific6’s founding partners, John Molina, is also one of Garcia’s top individual donors, and has contributed tens of thousands of dollars to his committees. Garcia, who helped found the Post, has had a large share of his campaign financing come from real estate and development interests, and he recently paid the Post $12,000 for political ads.

What does all that translate to for coverage? Well, as the conspirators will assure you, there’s no need to fret about a conspiracy. It’s not necessary for Garcia or Molina to hover over the shoulders of journalists, telling them what to write or not write about developments. Censorship is risky business, and bad PR. It’s much easier to simply hire a journalist to cover development who is already writing like a gentrifier. Then the coverage takes care of itself.

“I would say for Long Beach, the Broadway Block will mark the intersection between our artistic and cultural past and our creative future.”

– John Keisler, economic development director for Long Beach, in the L.A. Business Journal.

The physical and cultural spaces of our city are changing—have changed—in irreversible ways; but the most important aspect to all hosts of gentrification—be they architects, journalists, elected officials, bureaucrats—is not the colors generated organically by the people of a city, but the colors available to the palette of power.

To that end, such attacks on history as we have been exploring are granted an all-powerful euphemism: progress.

Progress, in my estimation, is the common denominator of arguments in defense of gentrification. If you ever find yourself discussing gentrification with someone who is either celebrating it wholesale, or nonchalantly excusing its effects, at some point they’re going to appeal to progress. Therefore, let’s end this essay by deconstructing our notion of it.

To give you just one example of what I mean, this is from an L.A. Times article about Acres of Books when it was finally sold:

Former Long Beach Mayor Beverly O’Neill said she was sad the bookstore had to go and was upset it might not relocate.

“It’s been there for years, and writers and readers and people have been so loyal. It’s been part of their lives, and I’m really sorry it’s leaving … The whole area is changing, and I know that it needed to change for the development and future of this city.”

That, in so many words, is the built-in excuse of progress, which can be applied to any change, at any time, in any way the gentrifiers see fit; and has the added bonus of allowing them to enforce their unquestioned devotion to progress with a feigned regret for having to do so. O’Neill sounds almost sorrowful in her statement above—but she knows that progress must continue its solemn march!

Therefore, I call progress a euphemism because its narrative tells us that economic development is both inevitable and impersonal. O’Neill captures the inevitable narrative well, but the impersonal narrative is expressed best by how depoliticized characters like Quigley and Ratkovich are in existing media coverage.

We often forget that on the other end of progress there are tangible, real human beings who will derive concrete economic benefit at the direct expense of existing residents. This is why I have attempted in this essay to politicize Quigley and Ratkovich, so that they cease to be nameless.

Progress, however, seeks to keep such powerful actors as anonymous as possible, and it does this by presenting itself as a kind of natural process—one which human beings don’t impose via their own choices and institutions, but simply wrestle with for the benefit of all. This conception of progress allows us to apologize to each other after-the-fact, reframing what we have taken as what has merely been lost—a sort of helpless sacrifice of history to time. And in return, of course, we get to keep our innocence.

But the reality is that progress is not a long-term march towards the future, but a short-term sprint at the future’s expense. Actors like Quigley, Ratkovich, and Onni Group, and politicians and bureaucrats within City Hall, are all chasing short-term profits and power at the direct expense of long-term residents. Progress, therefore, is not an unavoidable premise of human behavior, but a limitless excuse for it.

Lastly, progress is short-sighted towards the past and the future.

It is short-sighted towards the past via appropriation or erasure—as we can see by how the Broadway Block has not only required the displacement of all existing tenants from an entire city square, but also in how the project kept the tiny pieces of that history it thought were most useful, and repurposed them for its own benefit.

And it is short-sighted towards the future thanks to its own delusions of priority. By that last bit I mean the following:

The office towers of the ’80s seem so quaint to us now. Apparently a lot like bookstores. But we have to keep within our horizon the knowledge that one day—even if it takes a thousand years—councilmembers and city managers and landlords and developers will also seem so quaint. (A future worth fighting for!) It therefore takes a certain combination of stupidity and audacity to believe that even the newest and coolest and sleekest of developments won’t also one day become outdated; that it won’t be dismissed one day as obsolete by the same progress that birthed it; that it won’t be lost completely to the next wave of bulldozers.

When that day comes, it won’t be the parking lots, office towers, penthouses, or facades that we’ll regret having failed to preserve. It will be the bookstore.

The words in this essay belong solely to the author—but I hope you won’t let it stay that way. Reach out to me with ideas for art, stories, perspectives, solutions, and new politics: andrew@forthe.org. Alternatively, DM me on Instagram if that is more convenient: @oldschoolcarroll.

Help Us Create An Independent Media Platform for Long Beach

We believe that what we are trying to do here is not only unique, but constitutes a valuable community resource. We are dedicated to building a fiercely independent, not-for-profit, and non-hierarchical media organization that serves Long Beach. Our hope is that such a publication will increase civic participation, offer a platform to marginalized voices, provide in-depth coverage of our vibrant art scene, and expose injustices and corruption through impactful investigations. Mainly, we plan to continue to tell the truth, and have fun doing it. We know all this sounds ambitious, but we’re on our way there and making progress every day.

Here’s what we don’t believe in: our dominant local media being owned by one of the city’s wealthiest moguls or a far-flung hedge fund. We believe journalism must be skeptical and provide oversight. To do so, a publication should remain free from financial conflicts of interest. That means no sugar daddy or mama for us, but also no advertisements. We answer to no one except to our readers.

We call ourselves grassroots media not only because we are committed to producing work that is responsive to you, dear reader, but because in order for this project to continue we will also need your support. If you believe in our mission, please consider becoming a monthly donor—even a small amount helps!

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org