Long Beach has a Major Overcrowding Crisis

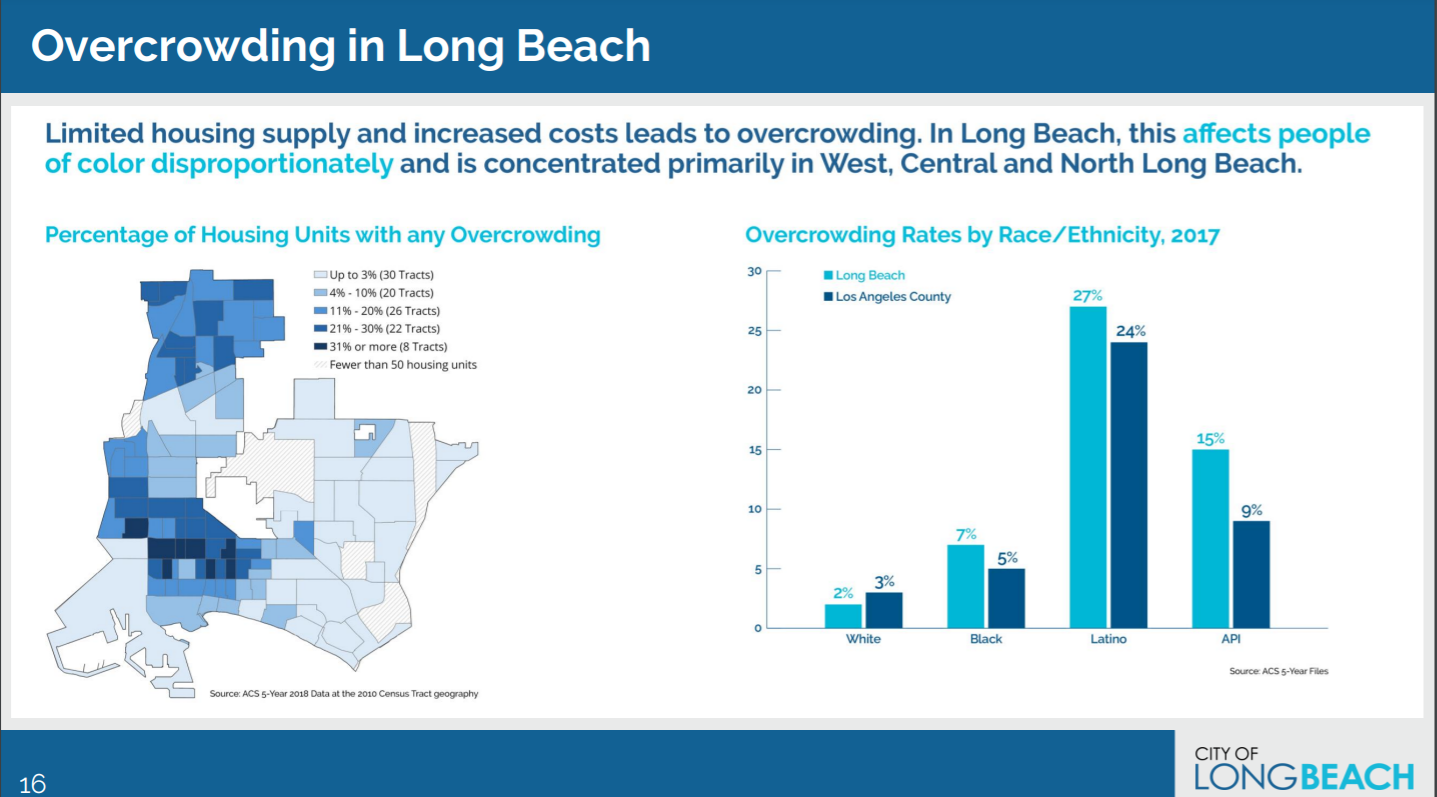

22 minute readLast month, Long Beach Deputy Director of Development Services Christopher Koontz, along with other city staff, presented a report on housing and development which included a map and some statistics on the city’s overcrowded homes. Currently, 11% of Long Beach residents, and 16% of renters, live in overcrowded conditions—defined as having more than one person per habitable room, excluding bathrooms and kitchens. 6.9% of renters experience extreme or severe overcrowding—more than 1.5 persons per room. Based on overcrowding data from other major cities, Long Beach ranks among the worst cities in the nation.

After the report, which was a preview of the city’s Housing Element due later this year, Councilmember Suzie Price (CD-3) asked if the city had more information on what causes overcrowding.

In the middle of a measured response that had some positives and some baffling negatives, Koontz acknowledged extreme overcrowding as a health concern, but dismissed non-extreme overcrowding, saying, “While it is a concern, it’s not a great concern.”

Explaining this distinction, he clarified the difference in his mind between overcrowding and “extreme” overcrowding. Here is the full quote:

“There are two levels of overcrowding. So the way it’s defined, there’s overcrowding, and we have a rate of 11% overcrowding, and while it is a concern, it’s not a great concern, because it’s calculated as number of persons per room. But where we have extreme overcrowding—which is about 7% of renters—that’s where it becomes a health concern. So it’s no longer a personal choice or preference or multigenerational housing.”

There isn’t a housing authority in the country that agrees with Koontz’s confused understanding of what separates “extreme” overcrowding from the overcrowding he isn’t greatly concerned with. Nowhere else is overcrowding “a personal choice or preference,” which only “becomes a health concern” once it is “extreme.”

There’s also that odd equivocation between overcrowding and multigenerational housing, as if somehow that excuses the issue or makes it no longer a concern. Even to the degree that multigenerational housing is more generally a preference or choice, that doesn’t mean it must take the form of crowded apartments. People don’t choose to live in crowded apartments.

When I emailed Koontz to ask him to clarify his comments, he said he was being mischaracterized, and that my questions were “incorrect” and “out of context.”

He wrote, “My intention was to make clear [that] extreme overcrowding is of paramount concern and is never by choice. Overcrowding is a serious issue facing Long Beach, as was made clear in the verbal and powerpoint presentation.”

I responded, “If your statements run contrary to the report, then your response to me cannot be to lean on the report, because that is precisely why I am emailing you.”

After all, it’s worth asking: why is Koontz being more forceful about the issue with me via email than he was with Price at an official meeting? The staff report, too, made it very clear that overcrowding is a serious problem. So why was Koontz less sure about it?

To some degree, Koontz is following City Council’s lead, and the council has shown almost zero interest in taking overcrowding seriously. It’s as if they know addressing it means first and foremost talking about the increasing cost of rent, which means confronting landlords.

The best part of Koontz’s comments to Price touched upon exactly that: “There can be a number of factors [contributing to overcrowding], but a common factor is simply cost, and doubling up in order to split housing costs among multiple members of the household.”

So if city staff present a report which clearly states overcrowding is a major issue, and Koontz tells Price point-blank that a major cause of overcrowding is the cost of housing, but the council essentially ignores the implications of all this, what is Koontz really supposed to do? His role is not to advocate or fight, let alone proselytize—it’s to answer questions, inform, and serve at the discretion and direction of elected leadership.

Still, to another degree, that makes the opening portion of his comments all the more problematic, because when Price asked a direct question, Koontz instead used the opportunity to downplay the issue. I believe at least part of his remarks can be accurately characterized as misinformation; and though correcting his comments with me via email is welcomed, it’s the council that needs to hear what a serious issue overcrowding is—not me.

There is also a larger cultural issue with accountability in this city—from city staff to electeds to other news outlets to the police. Wrong-doing is almost never admitted, and serious issues are rarely discussed in an open and earnest way. So instead of honest reflection about past mistakes and present crises, the public is usually treated to progressive posturing combined with a strange defensiveness.

The council’s dancing around the overcrowding crisis during the staff report, and Koontz’s subsequent response to me in our email thread, exemplify these larger problems, which go much deeper than any one person.

For example, Koontz informed me that even the Department of Housing and Urban Development has acknowledged that overcrowded housing is a choice for, in their words, “some segment of the population.” He sent me this link—an otherwise-random 2007 report that specifically cites, in a throw-away line on page 13, some small percentage of folks making more than $250,000 a year who still met the definition for living in overcrowded homes.

That seems both uncontroversial and irrelevant. But it also left me a bit confused. Is Koontz defending his statement or denying that he made it?

Maybe he meant to say that sometimes it is a choice—but that’s different from what he actually said. And, again, it’s also completely different from the staff report, which didn’t characterize overcrowding as a choice in any way. I would think staff probably had the wherewithal to realize that calling overcrowding a choice—even sometimes—in a city suffering among the worst rates of it in America, during a global pandemic and economic depression, would be at best counterproductive and at worst highly offensive.

Given that overcrowding tends to have disproportionate impacts on communities of color, I also asked if his comments could be seen as dismissive of the living conditions of the city’s Black and POC residents. Koontz responded, “The differentiation between overcrowding and extreme overcrowding and providing context to the data is not and is not intended to be dismissive of this important issue.”

That’s a good thing to hear. Still, it doesn’t take the comments back, and it doesn’t acknowledge they were said. When pressed one last time as to why he stated the city’s 11% overcrowding rate is “not a great concern,” and why he characterized it as a “choice,” he responded, “The characterization in your email that I clearly stated that overcrowding is a choice and not a health concern is not accurate.”

For transparency, you can listen to his comments from the council meeting in context below.

My heart tells me that Koontz simply made an honest mistake. But given the long history of neglect and exploitation that constitutes this city’s housing record, his comments also felt like he had just said the quiet part out loud.

OVERCROWDING AND COVID

We are currently in a global pandemic caused by an infectious disease, which means overcrowding of any kind is a particularly acute and present risk. All overcrowding at this moment ought to be a great concern. It’s impossible to discuss the pandemic’s spread, and its disproportionate devastation of communities of color, without talking about overcrowding. Not only is overcrowding directly linked to higher rates of COVID-19 transmission, it is also correlated with other health disparities which happen to make the virus more deadly.

A 2020 report studying COVID-19 in Massachusetts stated, “The most indicative measure of COVID-19 spread that [we] observed is the rate of crowded housing.”

Similarly, a New York University Furman Center analysis of the five boroughs of New York City stated, “ZIP Codes with higher rates of cases see higher rates of overcrowding.”

What makes the Furman analysis more frightening for Long Beach is that while both cities have a high percentage of renter households, Long Beach has a higher percentage of renter households that are overcrowded. The most overcrowded borough in NYC has 15% renter overcrowding. The average renter overcrowding for the entire city of Long Beach is 16%.

A 2020 ProPublica study of Chicago, which also found a correlation between overcrowding and COVID-19 infection rates, identified the worst zip code in the city as having an overcrowded rate of 10%. Long Beach’s average overcrowding for the entire city is 11%.

In several Long Beach census tracts, overcrowding is currently estimated to be over 30%.

Long Beach has a major overcrowding crisis. That’s partly why it’s so alarming to hear a member of city staff say overcrowding is “not a great concern.”

CalMatters looked at COVID-19’s spread in California and found the following:

- “The hardest hit neighborhoods had three times the rate of overcrowding as the neighborhoods that have largely escaped the virus’s devastation.

- Those neighborhoods also had twice the rate of poverty.

- In the least affected neighborhoods, about half of residents are white, while in neighborhoods most heavily burdened by the virus, 82% of residents are people of color.”

A pre-pandemic 2017 report from the California Department of Human Health concluded, “Residential crowding has been linked to an increased risk of infection from communicable diseases [and] a higher prevalence of respiratory ailments…”

Many of Long Beach’s overcrowded homes are in the west side of town, which faces disproportionate rates of respiratory illnesses—another COVID-19 comorbidity.

The U.N. Habitat for Humanity has for decades considered residential overcrowding to be one of the five hallmarks of a slum, along with “inadequate access to safe water; inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure; poor structural quality of housing; [and] insecure residential status.”

OVERCROWDED LONG BEACH TENANTS

Tomisin Oluwole

Ode to Pink II, 2020

Acrylic and marker on paper

14 x 22 inches

Click here to check out our interview with Tomisin Oluwole, a a literary and visual artist based in Long Beach.

Instead of gunking up our site with ads, we use this space to display and promote the work of local artists.

I wrote about the dangers facing Long Beach in my analysis of COVID-19 and overcrowding last April, and urged the city to change course on its development and housing priorities.

Sadly, the city’s report from last month’s special meeting found that, “Among renters, 16.2% experience overcrowding and 6.9% experience extreme overcrowding.”

The marks for homeowners are both much lower: 6.1% overcrowding and 1.6% extreme overcrowding, respectively.

The living conditions of Long Beach’s renter populations have been documented time-and-again as much worse than that of homeowners—whether it’s living in older housing or being more cost-burdened. A Beacon Economics report from three years ago summarized its own similar findings on the discrepancy like this:

“[Out of all the cities in the report, Long Beach] having the highest percentage of renter-occupied households that are overcrowded, but the second lowest percentage of owner-occupied households that are overcrowded, suggests that the inequality between homeowners and renters is more acute in Long Beach.” (pg. 9)

I had the chance to ask Abraham Zavala, an organizer with Long Beach Residents Empowered (LiBRE), about the overcrowded conditions facing tenants in this city. He says there are all-too-many stories to tell.

“For example,” Zavala begins, “there was one tenant, she was in a lease with one of her friends [who] was impacted by COVID. She lost her job, so now, collectively, they couldn’t afford to pay the rent. So this tenant then had to move in with a family member. It’s a full on family, and then plus herself. So now there’s like seven people in one home, you know, to like a two bedroom. And that’s just difficult to navigate.”

That story would contribute to the city’s “extreme” overcrowding rate, since there are more than 1.5 people per room. But as Zavala made clear to me, stories of overcrowding constitute a range of experiences, situations, and dynamics, and even when less extreme, overcrowding of any kind is still far from healthy.

“There are tenants who’ve had a family member who’s sick,” another story from Zavala begins, “and now they have to move in with them, for the care, and they’re worried about a landlord being over-scrutinizing as to why they’re there. And they explain to them, ‘Well, you know, they’re sick. This is my older parent. I’m trying to do my best as a child to support my parent.’ And so they’re worried the landlord is going to try to say they’re breaking the lease agreement because they’re taking care of their elderly parent, you know? It’s just crazy. It’s nuts. It’s those types of stories. That’s just a few examples.”

I asked Zavala if he felt any of these conditions were by choice.

“It’s not by choice,” he replied. “Not at all. It’s a forced condition. It’s a lack of response, oftentimes in policy, to address these issues.”

The problem of poor policy seems to extend from at least certain actors in the planning department, to City Council, and all the way to Mayor Robert Garcia. Last summer, the mayor dishonestly boasted that, under his leadership, Long Beach had built “thousands of working class homes.” We revealed that’s a lie. In fact, instead of building homes—affordable or otherwise—the 2018 Beacon report ran the numbers and concluded that for every one unit of housing Long Beach gained from 2010 to 2016, it lost 2.37 units (pg. 5).

Under Garcia’s tenure, as of our counting last year, the city has permitted the construction of more hotel rooms than affordable homes. And while Long Beach’s hotel rooms are now emptier than they’ve been since maybe the crash of ‘08, the city’s renters are among the most overcrowded in the U.S.

I think back to my own story of displacement—when my landlord decided to follow the city’s lead and turn my home into a hotel. Myself and the other tenants were alerted of this sudden change just in time for the landlord to avoid having to pay any relocation assistance. This was in the middle of 2019. By January, COVID-19 was here.

Over a year later, and one of the big issues facing renters in Long Beach today is a loophole of another kind: landlords are getting around pandemic-related tenant protections by claiming they plan to make substantial remodels to the building, and so they need to empty everyone out.

“Guess what, now you have to move,” Zavala tersely puts it. “We need to clear you out of your apartment, and people are left scrambling for housing, which leads to more concentrated groups of people living in one space.”

“In the absence of any rent control or any kind of affordable housing,” he asks, “what are folks left to do?”

Unfortunately, these issues are also impacting some communities more than others. The map and chart below show that the west, north, and downtown areas are particularly affected, and that the city’s Latino populations suffer the highest rate of overcrowding—over 13 times higher than white people, for example, who suffer the least.

“It’s typically POC communities—Black and brown and other communities who are low-income—who are being impacted by [overcrowding],” Zavala confirms.

The map shows some Long Beach census tracts have overcrowded rates in the 30s. For comparison, the most recent map I could find on this issue in New York City reports its most overcrowded neighborhoods have a rate in the mid-20s.

“Whether it’s eviction or loss of job or COVID—all these things are kind of like a storm,” Zavala says, “taking a toll on tenants.”

You’ll also notice that the above blue map looks suspiciously similar to the following orange map, which measures COVID-19 infection rates in the city by zip code:

In fact, they’re basically identical…

This is not to say that overcrowding is the main or only cause of the spread of COVID-19 infections in these areas, since a variety of factors may be at play. Still, it’s quite clearly one of the factors, and should be taken more seriously. So when someone says overcrowding is “not a great concern,” it’s really, really difficult not to hear, “The living conditions of Black and POC residents are not a great concern.”

And that’s the undertone of this discussion, or lack of discussion—especially when the council essentially ignores a report and goes on with their agenda as if city staff didn’t just show them a map with dark blue census tracts symbolizing areas where one out of every three residents is living in overcrowded conditions during a pandemic.

Though the entire City Council had a chance to reflect on the data provided by the report, only Price asked a direct question related to overcrowding, and only Councilmember Stacy Mungo (CD-5) expressed concern about it, sharing an emotional anecdote about a family in her district living in an overcrowded home. It’s amazing to me that the two councilmembers from districts with perhaps the least overcrowding were the only ones who seemed to care about the issue.

As just one counter-example, Councilmember Mary Zendejas (CD-1) appeared clueless about the map city staff shared that painted her district as perhaps the most overcrowded in the city, and chose instead to spend her time praising the small number of affordable projects the city has approved—which, given that she is an elected representative within the city, basically amounts to her patting herself on the back. She then made a single reference to “overcrowdedness” in relation to parking.

One of my questions to Zavala concerned this lack of response: “Why doesn’t the city seem to care about this overcrowding issue as much as they should?”

“Whether they care or not,” Zavala says, “I can’t speak for that. But I would say that our folks, our tenants who organize with us, have done tons of public comment [at City Council meetings]. I don’t know what else people need to do to raise this as an issue.”

And what about the “why?” of overcrowding—the initial question posed by Price, and fumbled by Koontz? Zavala offers a pretty simple answer.

“Why are they overcrowded?”, he asks. “The rent’s high, and people need to cohabitate with family or friends and find any way possible to pay an extremely high amount of rent.”

The 2018 Beacon report agreed: “Over the past few years, the housing market in Long Beach has been marked by declining vacancy rates, relatively slow growth in housing stock, rapid increases in home prices and rents, and relatively high levels of overcrowding…” (pg. 2)

The report also found, based on 2016 data, that over 16% of Long Beach’s renter households were overcrowded (pg. 7)—more at that time than Sacramento, Oakland, Fresno, and every other city in the report.

Apparently Long Beach hasn’t made much progress on that 16% in the past five years. Maybe it’s time to elevate the concern level to “great”?

“You want to put numbers to it, that’s one thing,” Zavala insists near the end of our conversation, “but the stories, the qualitative, that’s what we should be focusing on. No percentage should be acceptable. If you hear the stories, or if you work with tenants, you learn to appreciate that we shouldn’t wait for it to be an alarming percentage to respond, you know? What percentage do you need to reach to acknowledge the crisis?”

Editor’s note: This article initially referred to Christopher Koontz as the Planning Bureau Manager, and thus the headline mistakenly called him the “Planning Chief.” The headline reference was removed and the mention in the article was updated to reflect that Koontz is the Deputy Director of Development Services.

andrew@forthe.org

andrew@forthe.org